I am not trying to scare you.

I don’t issue seasonal hurricane forecasts for the clicks, the clout, the hearts, or the stars. I have no agenda other than being right and not causing unnecessary anxiety.

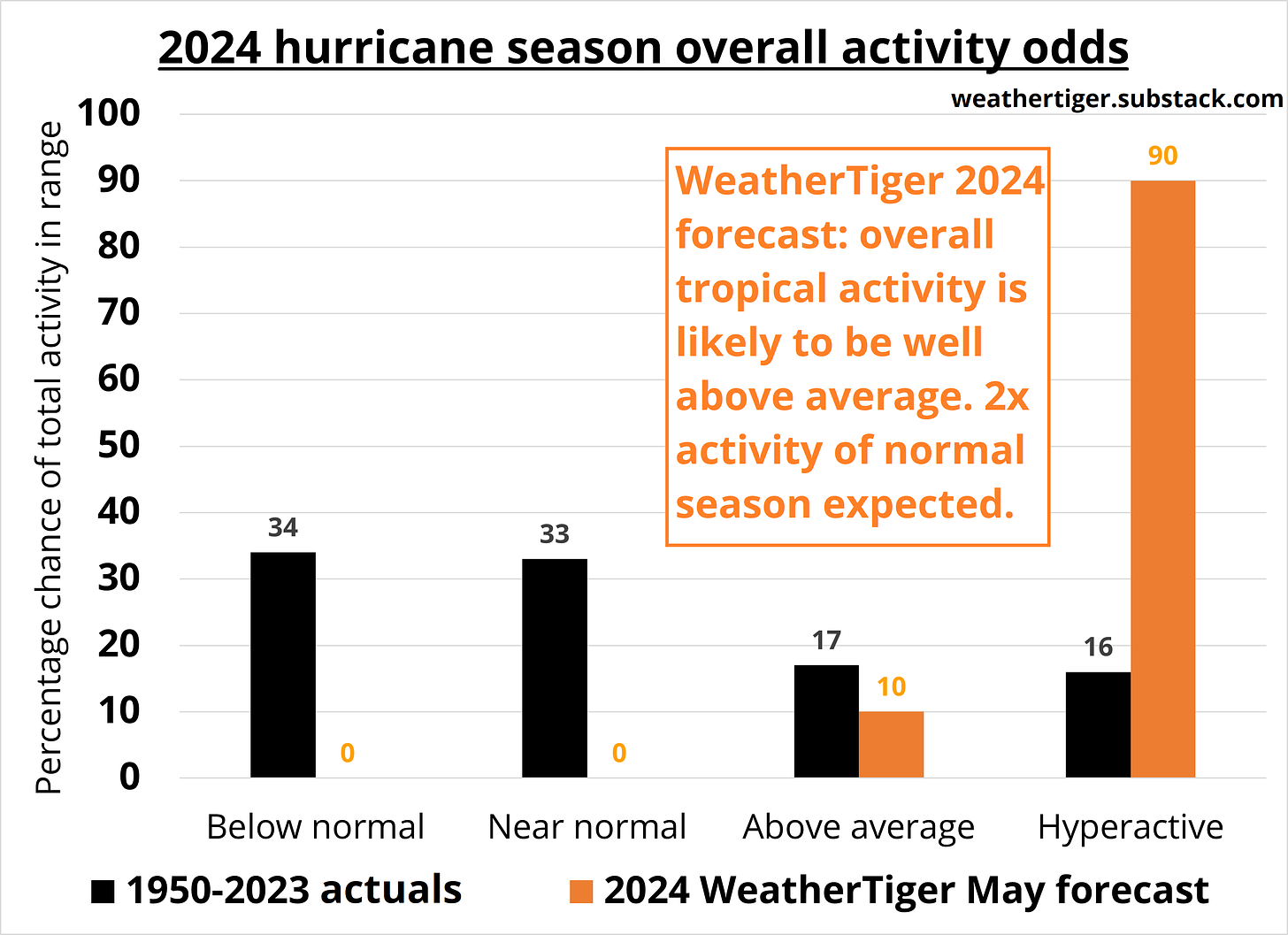

Unfortunately, while I am not trying to scare you, WeatherTiger’s outlook for the 2024 hurricane season is objectively unsettling, especially with the Gulf Coast already brutalized by severe weather in its prologue. The most likely outcome is overall tropical activity more than twice average, with minimal chances of a quiet season and greater than 90% odds of a hyperactive year amongst the top dozen since 1950.

First, a little about me for those who are new around here: I’m Ryan Truchelut, Chief Meteorologist at WeatherTiger, a Tallahassee-based weather analytics and forensic meteorology firm. I have a doctorate from Florida State and 20 years of forecasting experience, including three years delivering a signature blend of Florida-focused hurricane analysis plus cringeworthy dad humor at WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch. Expect a weekly tropical overview column between June and October, with more frequent forecasts as the situation warrants. I also enjoy running the hidden pine trails of the forest, tasting the sun-sweet berry flavors of LaCroix, and the riches of dad life with my two kids, whose names are both derived from the 2024 storm list. I take the Tropics seriously.

As part of that commitment to you, I’ve already laid in a stockpile of LaCroix at WeatherTiger World HQ, which working late (because I’m a forecaster) will turn into a mighty pyramid of empty cans by season’s end. But how high will 2024’s LaCroix ziggurat be? Let’s unpack that hyperactive forecast like a pallet of naturally essenced sparkling water and translate it into U.S. hurricane landfall odds.

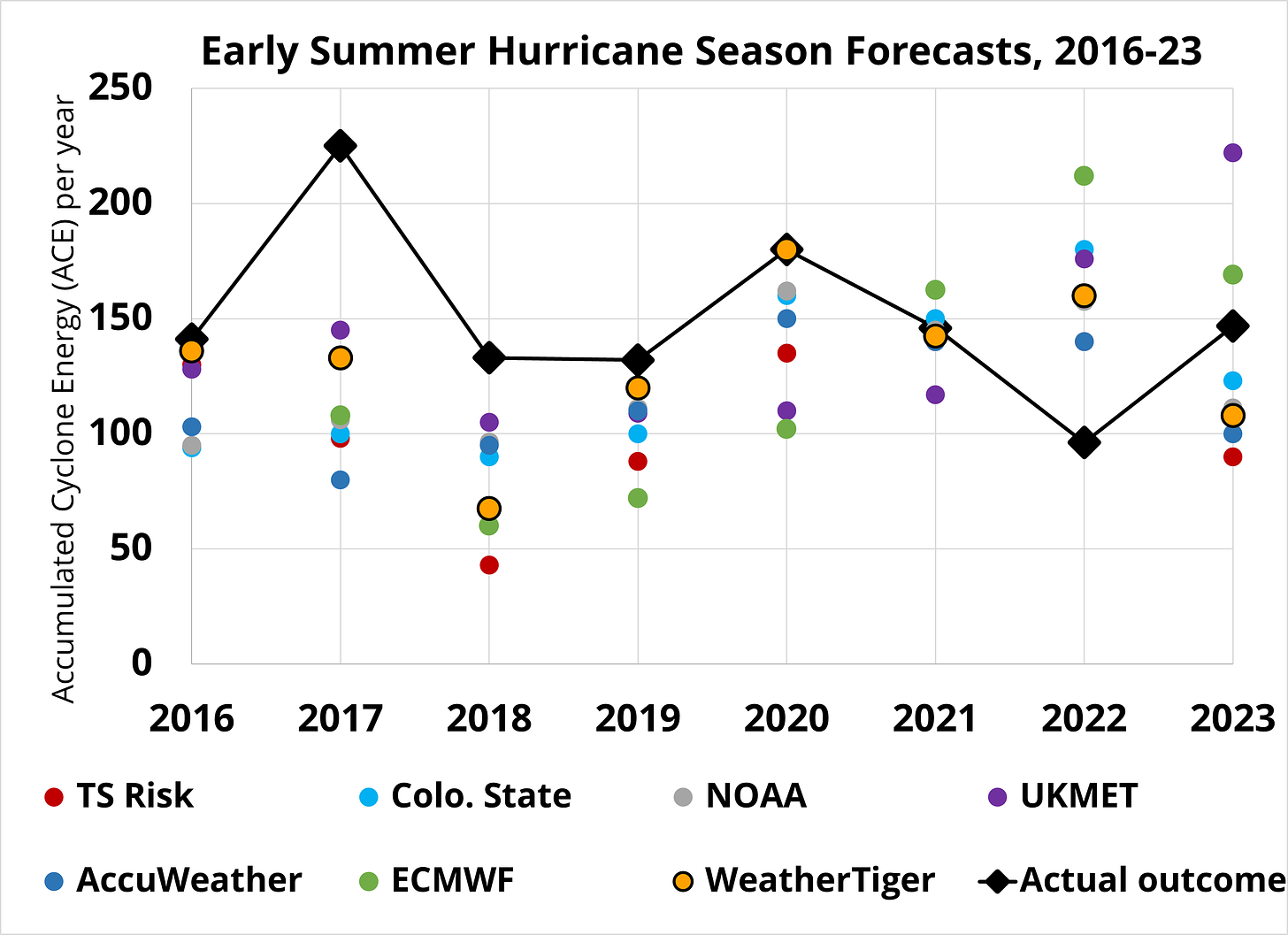

Before getting into specifics, note that seasonal outlooks do not “always predict a busy season,” emails after I write this forecast each year to the contrary. The facts, not vibes, show the pre-season outlook consensus has underestimated seasonal activity in five of the last eight years, including 2023. WeatherTiger’s pre-season forecast, as accurate as they come, has undershot three times, missed high once, and been close to correct four times since 2016. The lone overestimate? The 2022 season, in which Ian caused $113 billion in damage and WeatherTiger’s analytics highlighted an elevated chance of Florida landfall threats.

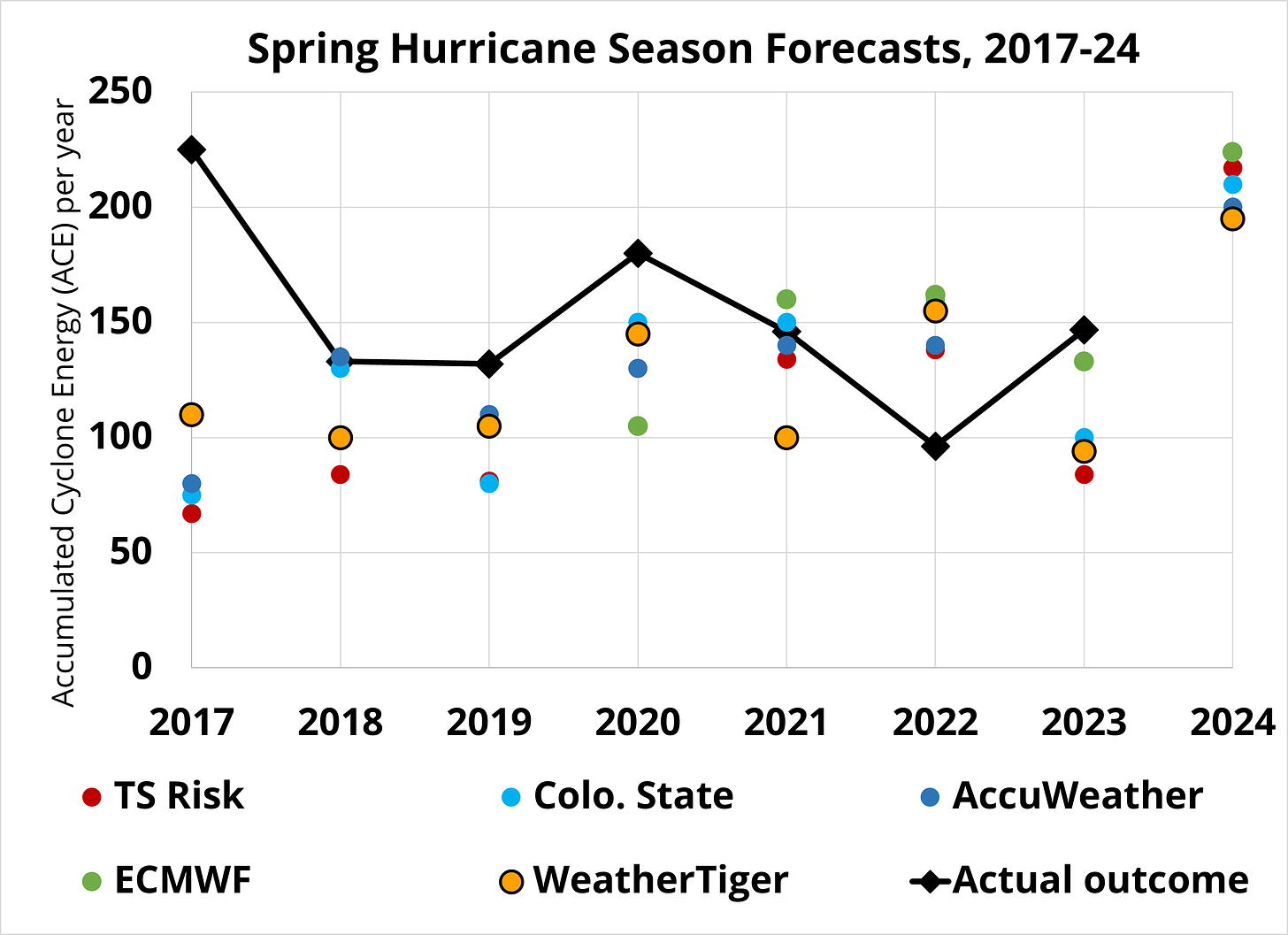

Seasonal forecasts are imperfect, but they have historical skill originating from the persistence of ocean temperature anomalies between spring and hurricane season, influencing how many and where storms develop. Most of the time, these leading indicators present a mixed portrait of the season ahead, as was the case in 2023. However, WeatherTiger’s March 2024 outlook alarmingly showed that reliable predictors all signaled a busy year. It wasn’t just us. Every credible forecast group, from Colorado State to the European Centre, has since issued their most aggressive spring hurricane season outlooks ever, most calling for around twice average activity.

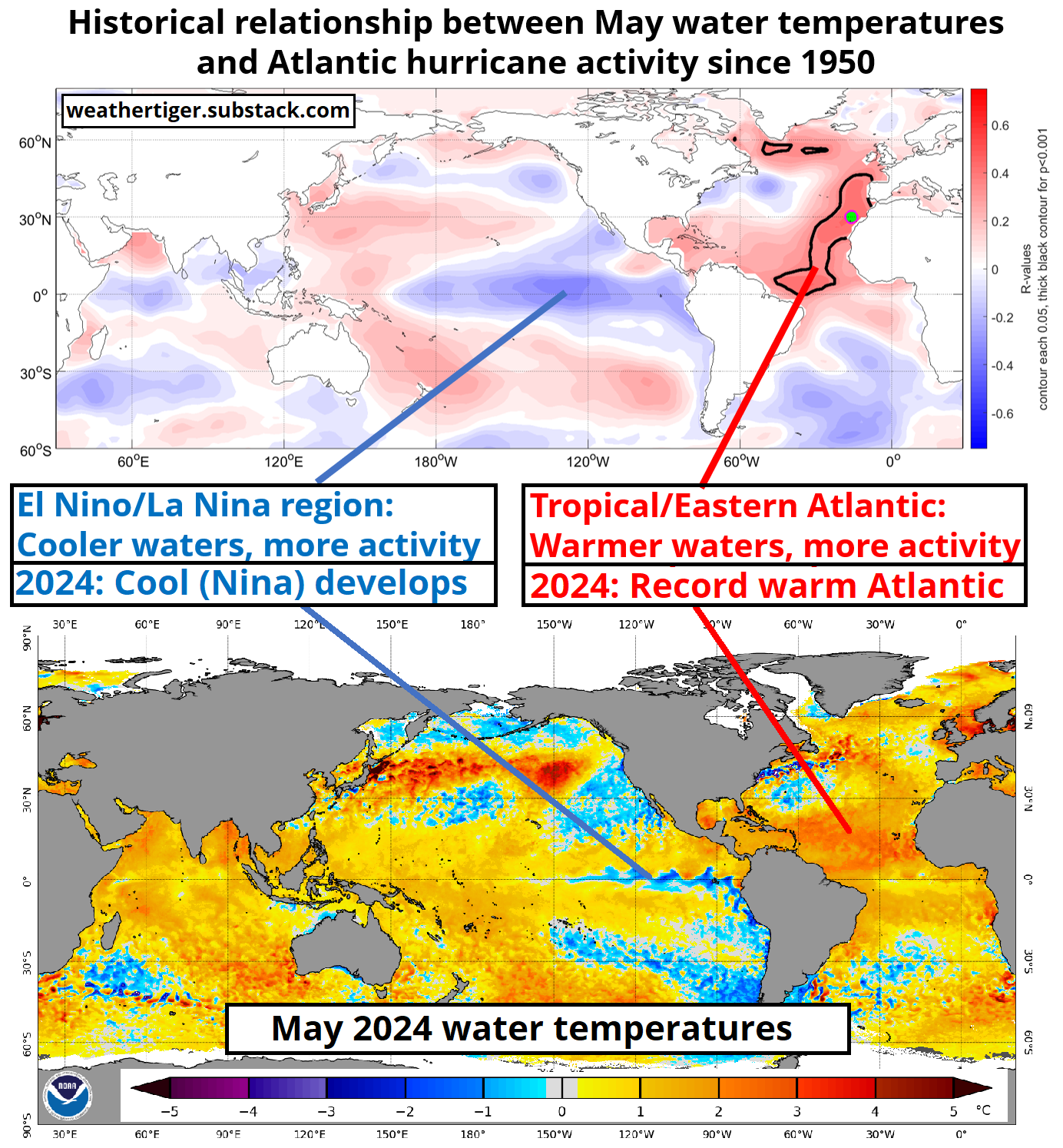

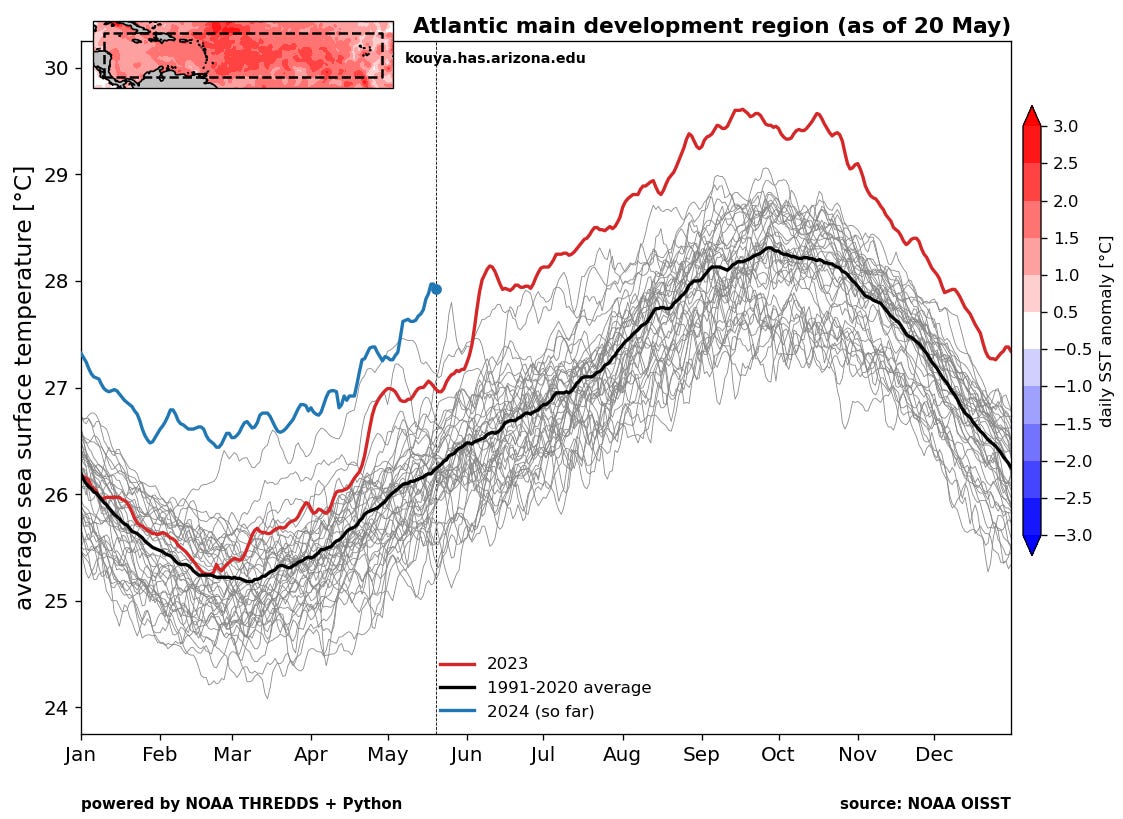

A forecast for a BOGO hurricane season is an extraordinary claim, and as such, requires extraordinary proof. And, indeed, extraordinary is the word for what is happening with water temperatures in the Atlantic. The historical relationship between warm anomalies and increased hurricane activity is strongest in a hook across the Tropical and Eastern Atlantic, and it is precisely these regions where ocean warmth is now the most pronounced relative to normal. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region are running a record 3-5°F above 1991-2020 averages, and are as warm today as they typically would be in late August. These warm waters run deep, and there is no sign of a mean reversion. Like Billy Joel, SSTs are going to extremes in 2024.

You might be wondering why the Atlantic isn’t cranking out hurricanes if water temperatures are already in midseason form. The answer is that atmospheric conditions also matter. Upper-level winds over the western Main Development Region have been inconducive (as usual) for tropical development in May, and are likely to remain that way for at least several more weeks. Elevated wind shear has been spurred by the last gasps of 2023-24 El Nino in the Equatorial Pacific, which is linked to unfavorable atmospheric conditions for hurricane development in the western Atlantic.

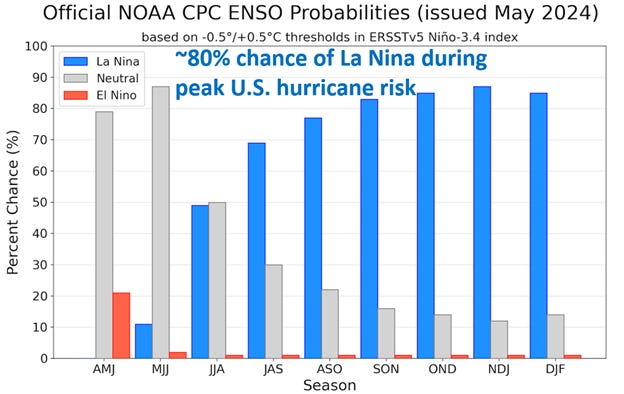

Unfortunately, El Nino met its expected demise a few weeks ago and cool SST anomalies are now spreading westward towards the central Equatorial Pacific. In a few months, these cooler waters will likely sync with a symbiotic wind pattern, birthing the fourth La Nina event of the past five years.

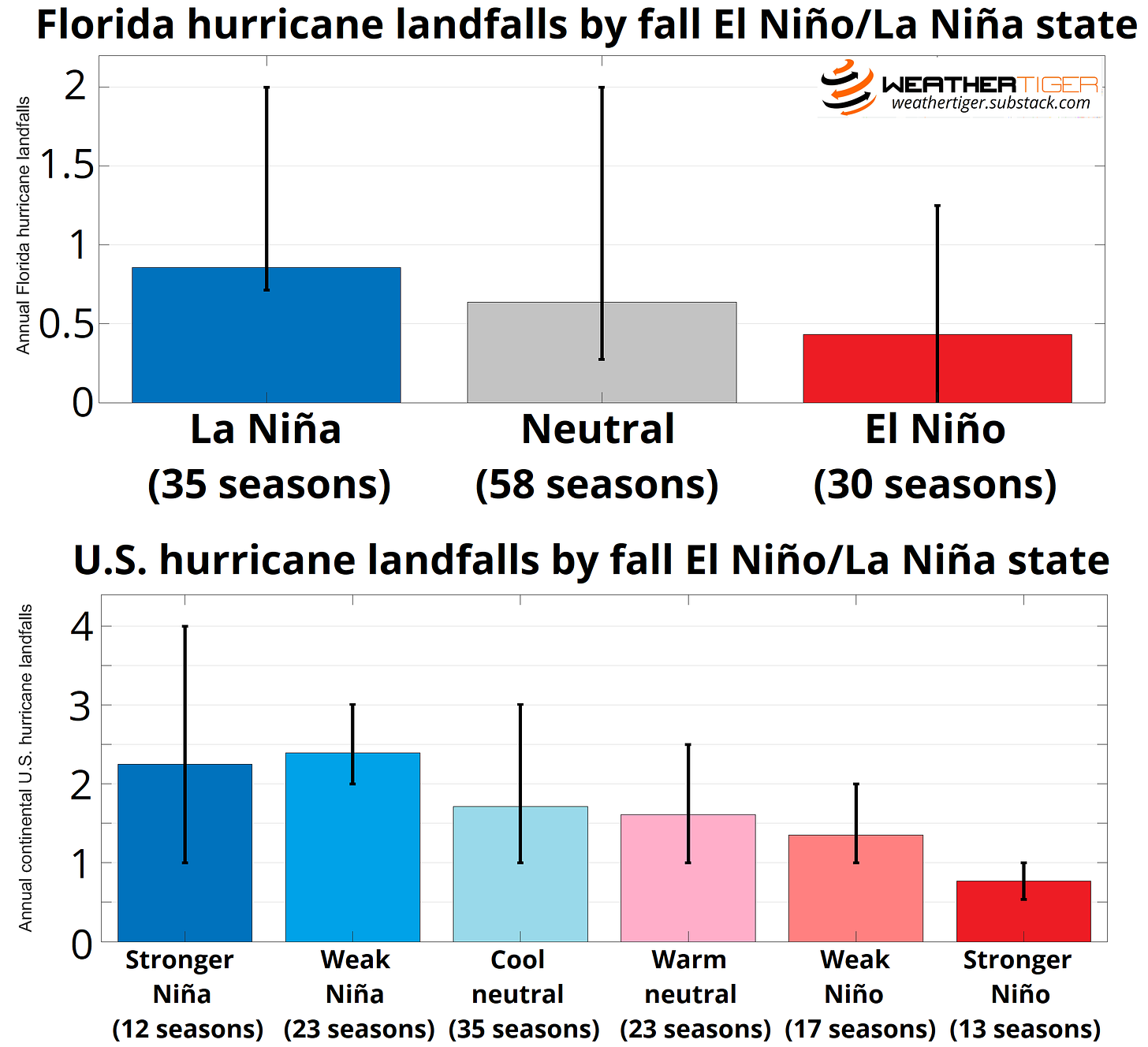

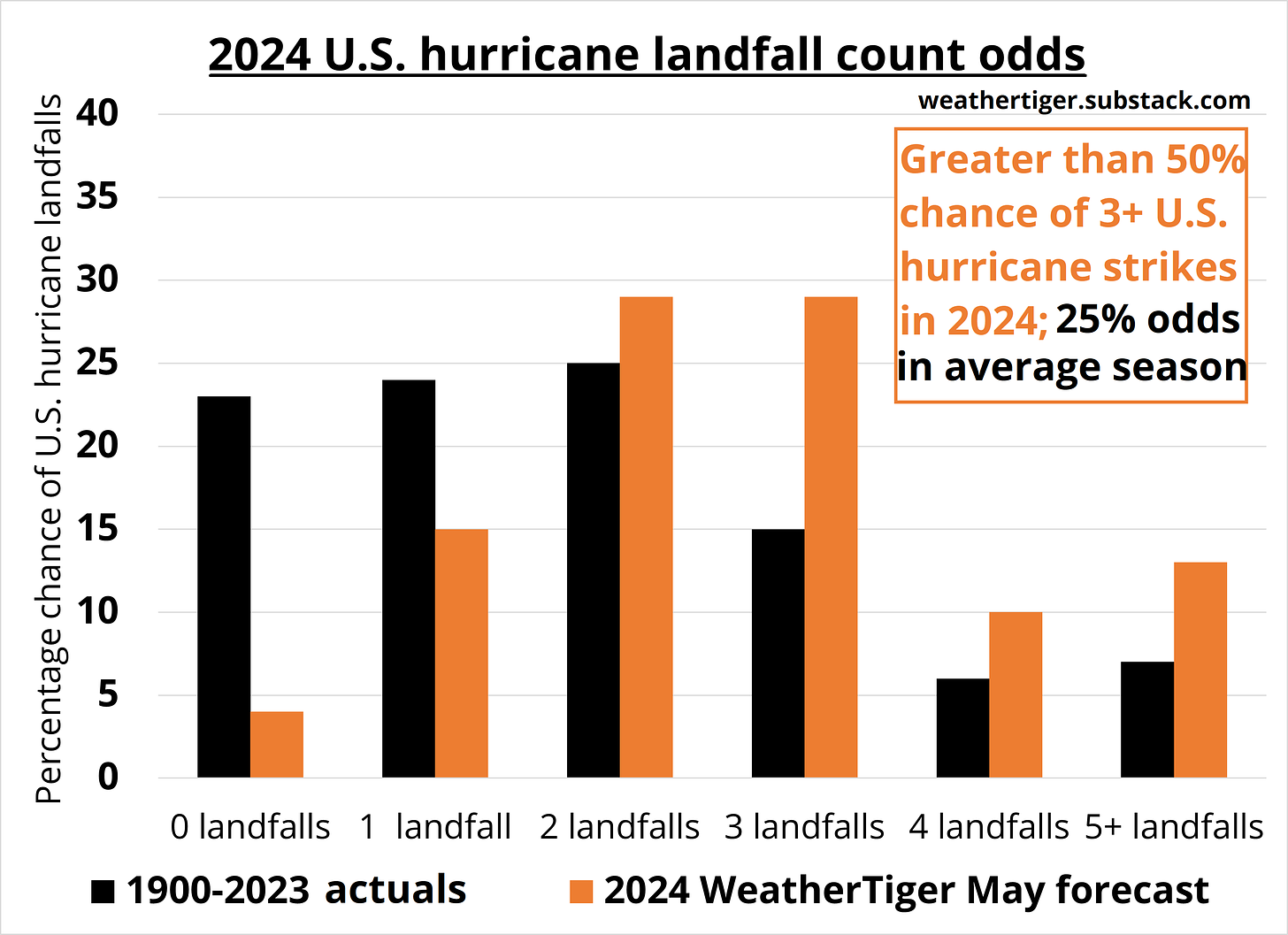

These La Ninas are a big part of why hurricane seasons since 2020 have felt punitive. Years with a peak season La Nina tend to have less wind shear over the Gulf, Caribbean, and western Atlantic, and as such, average about twice as many U.S. and Florida(!!!) hurricane landfalls as El Nino years. Some ambiguity remains about the eventual strength of the 2024 La Nina, but history shows that distinction to be mostly immaterial to landfall risks: weaker or stronger, all flavors of La Nina average the same number of U.S. hurricane impacts.

Overall, what little has changed since WeatherTiger’s March outlook has changed for the worse, with less uncertainty in the timing of La Nina development, Atlantic SSTs trending ever more berserk, and the general Big Dogs attitude yet more insouciant. WeatherTiger’s algorithm quantifies these key predictors to optimize odds of how hurricane season may play out. Of the 11 factors WeatherTiger’s model is currently integrating, a whopping six are strongly positive, with three more favorable, one neutral, and just one weakly negative.

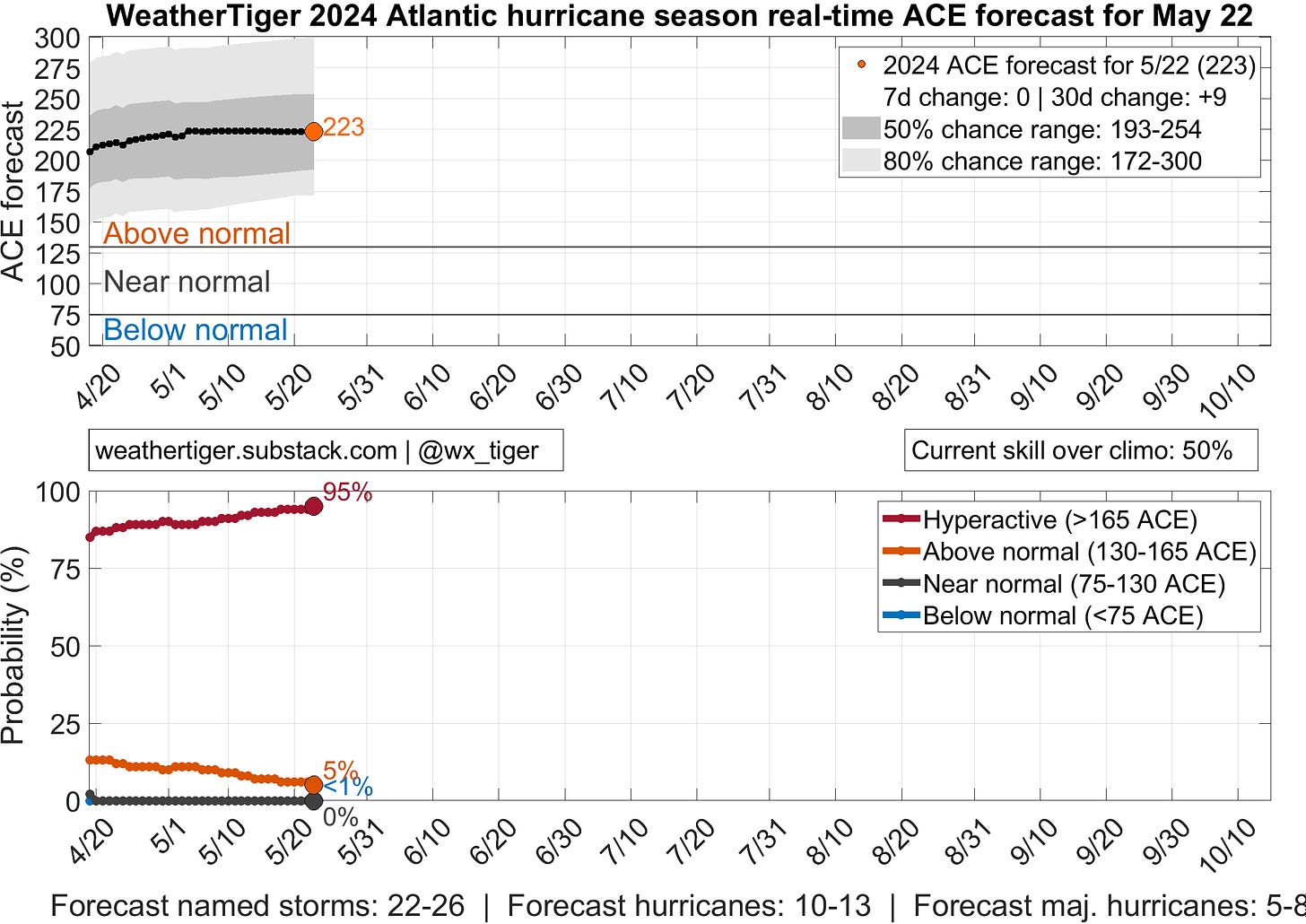

As such, there is a 90-95% chance of a hyperactive hurricane season with at least two-thirds more tropical activity than normal and a most likely outcome of about 220 units of Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), which is over twice the average ACE since 1950 and up another 10% since our March forecast. The 2024 season has 50-50 odds of landing in the 22-26 tropical storm, 10-13 hurricane, and 5-8 major hurricane ranges.

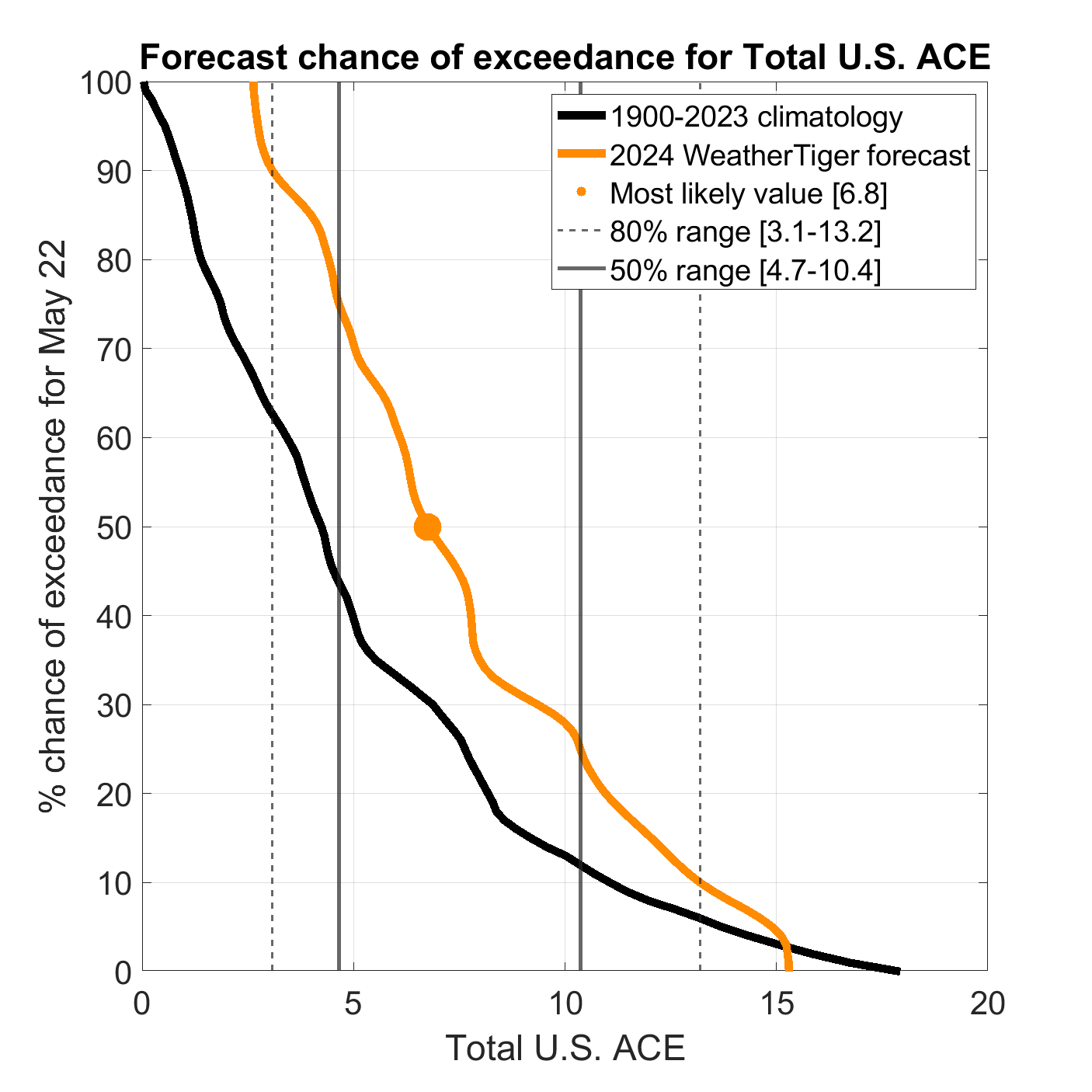

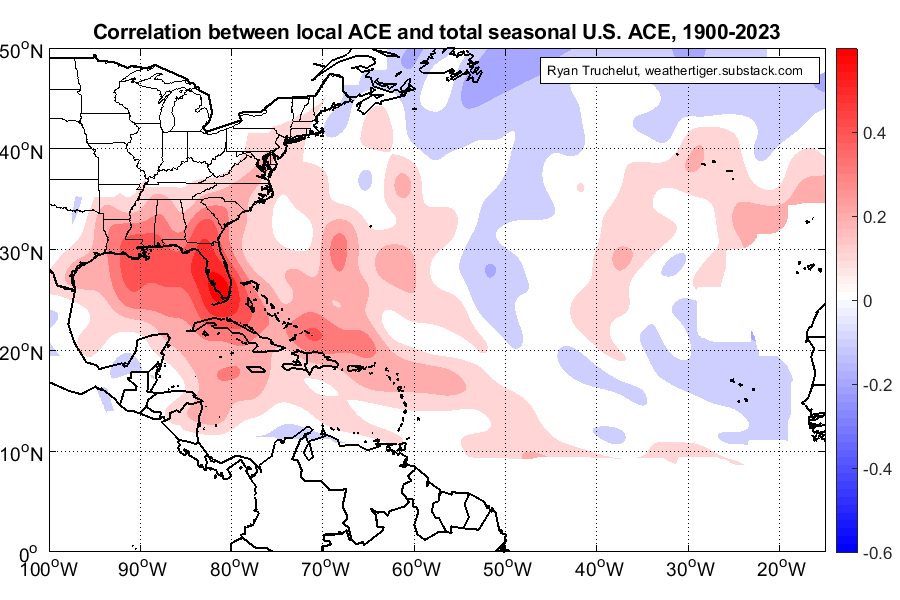

However, forecasts of Atlantic tropical activity have limited utility in understanding what counts, landfall risks. For instance, storms occurring in the eastern half of the Atlantic have no or even a slight negative correlation with U.S. landfalls, as tropical waves that develop there are more likely to curve north into the open Atlantic. Even if we knew with metaphysical certitude how much tropical activity would occur this year, that would put us only about one-third of the way to accurately predicting the total severity of U.S. impacts. The rest is determined by where storms develop and how they move. With only about 4% of climatological Atlantic ACE occurring near or over the continental United States, luck plays a major role as well.

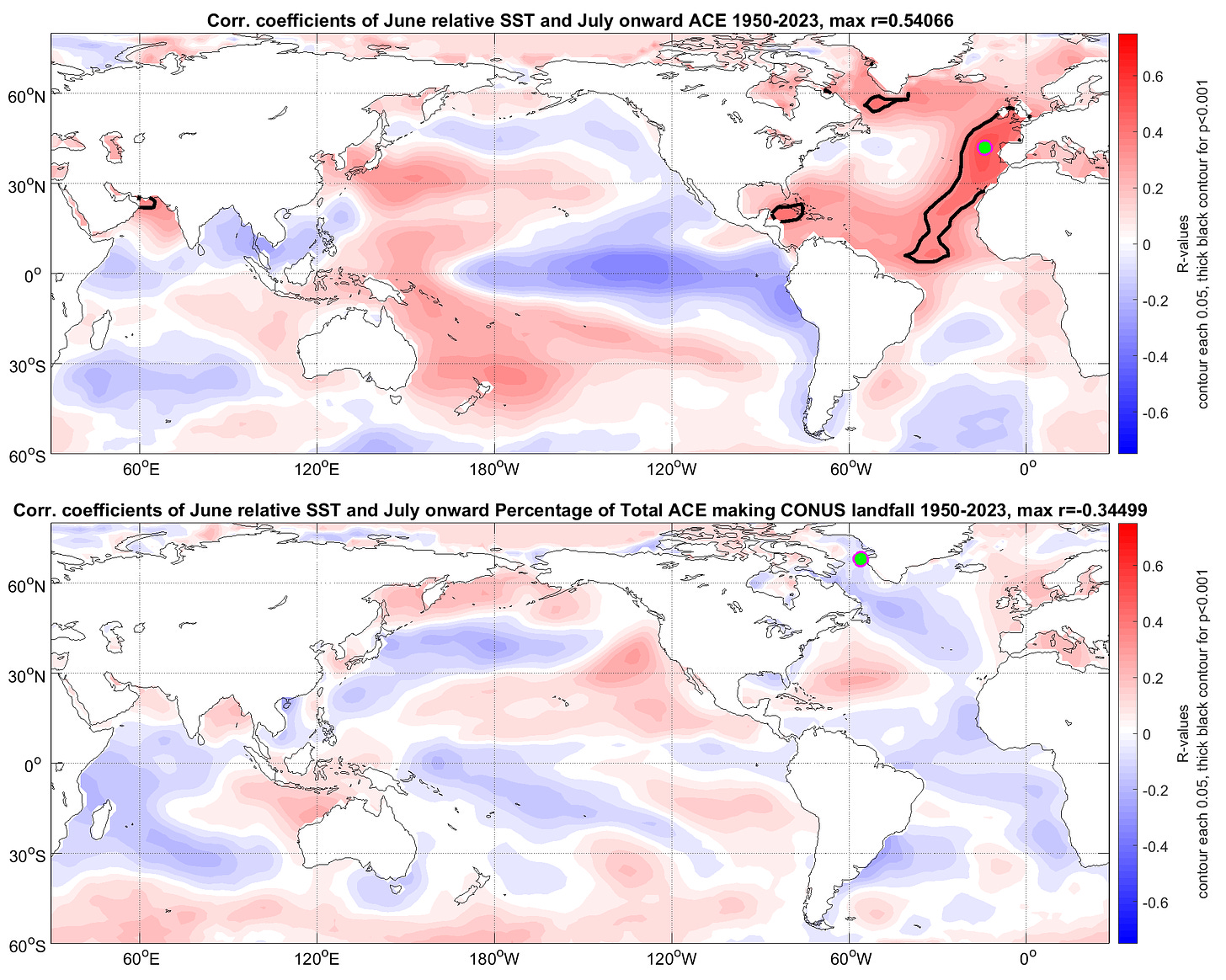

Rigorous seasonal forecasting of U.S. landfall risks is tough, because key climate modes can both promote more tropical activity and contribute to a steering pattern directing those storms away from land. Above are the spatial correlations of June relative SSTs to seasonal ACE (top) and the percentage of total seasonal ACE occurring near or over the continental United States (bottom). This figure shows those cross-purposes at work: La Nina favors more Atlantic ACE, but there is no correlation between the La Nina/El Nino region of the Pacific and what percentage of a season’s activity hits land. A warmer Tropical Atlantic makes for a busy year, but a cooler Tropical Atlantic seems to modestly favor more U.S.-directed steering winds. Warm waters in the northern Pacific and off the U.S. West Coast, associated with the positive phase of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), seem to have the strongest link to landfall percentages, but even this relationship is modest. (For more details on these connections or just to save money on prescription sleep aids, read my dissertation.)

Those weak correlations indicate that it simply isn’t possible to forecast peak season steering months ahead of time. Still, WeatherTiger’s targeted seasonal model for U.S. hurricane landfall risks sifts through subtle signals that separate catastrophic from busy but forgettable years. The 2010 season was hyperactive in terms of total activity, but strongly negative PDO likely played a role in keeping storms away from the continental U.S. that year—unlike the hyperactive and destructive 2004, 2005, and 2017 seasons, in which the PDO was more neutral. Right now, our landfall risk model is tilting away from worst-case scenarios, though still projecting about 7 units of U.S. ACE versus a typical 4.0-4.5, an 80% chance of at least two U.S. hurricane landfalls, and a 65-70% chance of at least 1 U.S. major hurricane landfall in 2024. Those risks are well above normal, but the forecast is not nearly as aggressive as our overall activity guidance. Take these landfall risk forecasts as the uncertain estimates they are.

A final twist to WeatherTiger’s seasonal models is their unique real-time capability. Each day this season, our algorithm will translate a snapshot of the ocean and atmosphere into fresh odds of overall activity and U.S. landfall outcomes. This served readers well in 2022 and 2023, as our models ably stayed abreast of mid-season forecast swerves in live time. Check out our updated 2024 daily predictions here, including supporter exclusive Florida and real-time U.S. landfall odds that can also be viewed by paid subscribers after the paywall jump.

In conclusion, the 2024 hurricane season is nearly certain to be more active than average and has a roughly 25% chance of being the busiest on record. Key concerns include deranged Atlantic warmth, conducive upper-level winds, and little chance either will change course over the next three months. On the plus side, busy seasons sometimes have muted U.S. landfall impacts, and the Choco Taco is supposed to return this summer. That’s about it. There’s no normal way to do anything anymore.

So, it’s time to plan for hurricane season. I’m not trying to scare you, but I am trying to make a rational case for getting ready before the LaCroix cans are stacked as high as an elephant’s eye and things get emotionally raw like a quadruple-length Bluey episode. Since 2017, eight Category 3 or higher U.S. hurricane landfalls have caused a half-trillion dollars of destruction, and we’ll be darned lucky if it doesn’t happen again this year. Prepare your hurricane kit, know what to do if you receive an evacuation order, and trim those trees if cruel nature hasn’t already done it—you’ll be glad you did. Then crack open a refreshing pamplemousse, limoncello, or razz-cran and settle in, because we’ve got a journey ahead of us. Keep watching the skies.

Florida landfall odds (paid supporter exclusive)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to WeatherTiger's Hurricane Watch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.