Atlantic Hurricane Season First Look: March 2024

Atlantic and Pacific indications are lining up for large-and-in-charge hurricane season.

Lead, follow, or get out of the way.

This canine koan summarizes our predicament as the rough beast that is hurricane season slouches towards birth. With Atlantic warmth leading and a favorable La Nina in the Pacific soon to follow, there is every indication that 2024 will exemplify that Big Dogs attitude. Whether or not coastal residents have to get out of the way remains to be seen, but like the non-athletic leisurewear of '90s dads everywhere, the available sizes for the upcoming hurricane season seem to range from L, at minimum, all the way up to XXXXL.

Time to dig in on the key pre-season factors as we prepare to involuntarily leave the porch and run with the big dogs in 2024.

Lead: Atlantic ocean temperatures

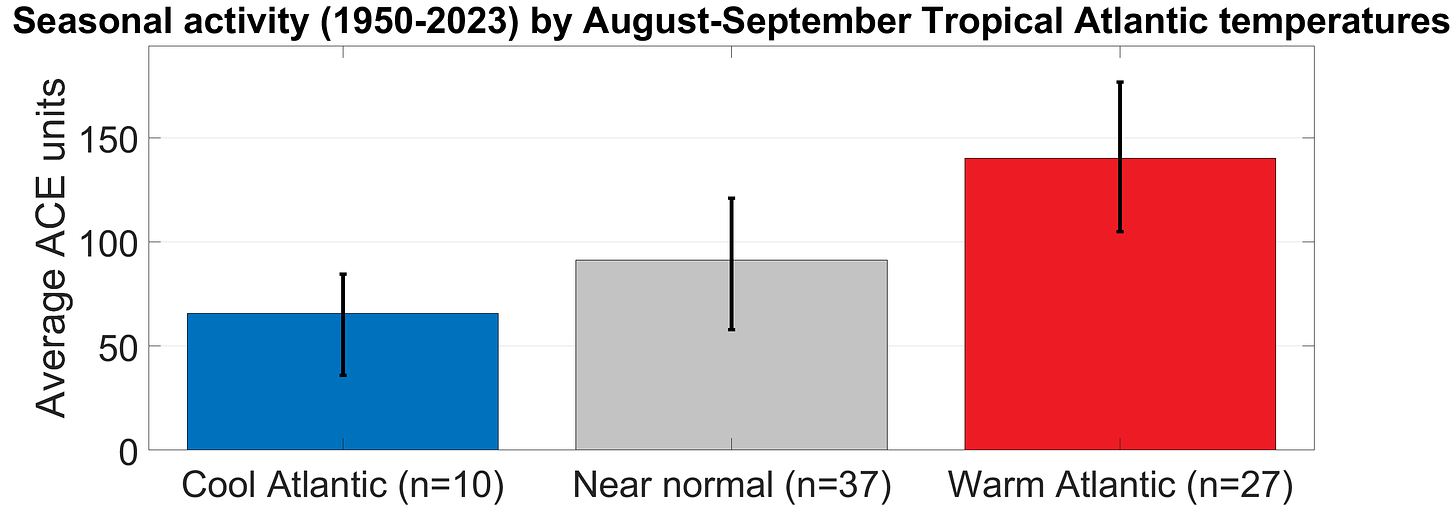

Historically, Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs) between Central America and West Africa during August and September are a strong indicator of how busy the hurricane season will be. Since 1950, years in which the Tropical Atlantic is at least 0.25°C warmer than normal average two-and-a-half times the hurricane activity of years that are at least 0.25°C cooler than normal. All else equal, that makes sense as warmer waters provide more fuel for a storm’s thermodynamic engine.

Atlantic SSTs can be volatile, though. WeatherTiger’s initial 2023 hurricane season outlook called for a near-normal year due to expectation that modest Atlantic warmth would offset a developing El Nino. While El Nino unspooled as expected, Atlantic SST warmth in 2023 proved more exhibitionist than modest. Starting in May, SSTs in key regions of the eastern and Tropical Atlantic soared to all-time records, leading to a busier hurricane season than spring forecasts predicted.

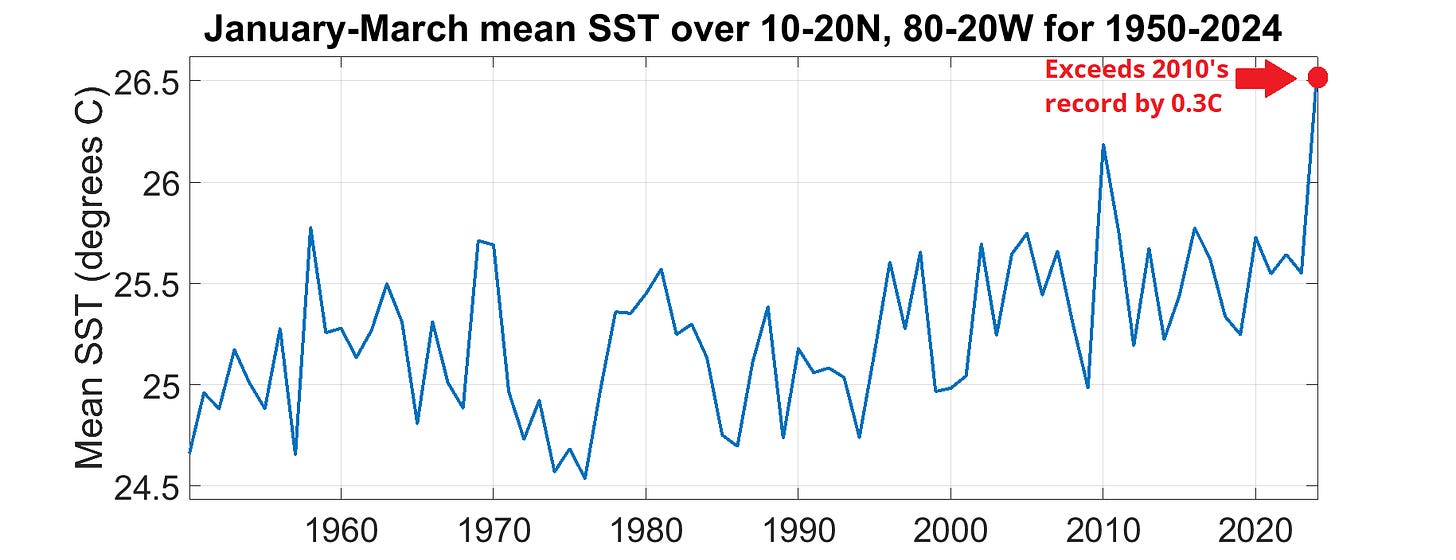

As if it was contained in an unnecessarily large and expensive water bottle, the Tropical Atlantic has remained extraordinarily warm through winter and into early spring. Average water temperatures since January in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region (MDR) are 1°C above last year, crushing previous highs by almost 0.3°C. In terms of total heat content, the Tropical Atlantic is as energetic now as it typically would be in mid-June. While Atlantic SST anomalies can change with weather patterns through summer, even if the Tropical Atlantic warmed up the least it ever has warmed between now and September, it would remain well above average for the peak of hurricane season. In short, there is high confidence that the Atlantic MDR will be strongly conducive for storms this summer and fall. The Atlantic is so hot right now, it’s basically Hansel.

Follow: El Nino/La Nina conditions

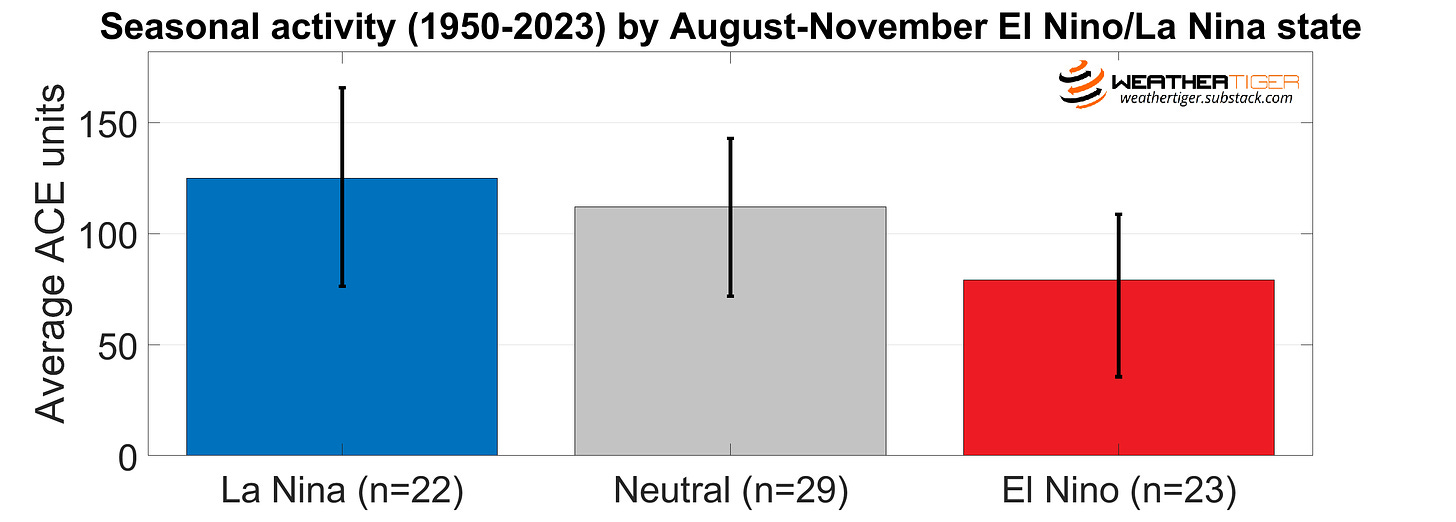

While the El Nino that developed last summer in the Pacific couldn’t keep the lid on the Tropical Atlantic’s boiling kettle and 2023 clawed out above average hurricane activity, El Nino nevertheless tastefully restrained storms in the Caribbean and western Atlantic via unfavorable upper-level winds. Those predictable shearing winds aloft during an El Nino are why hurricane forecasters follow the Pacific so closely; an average Atlantic season during an El Nino is nearly 40% less active than one with an ongoing La Nina.

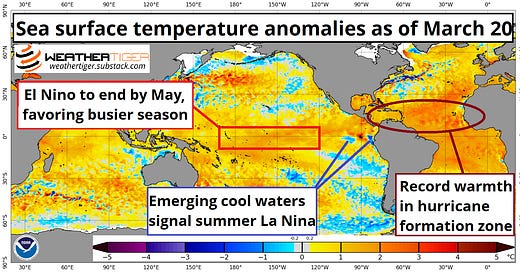

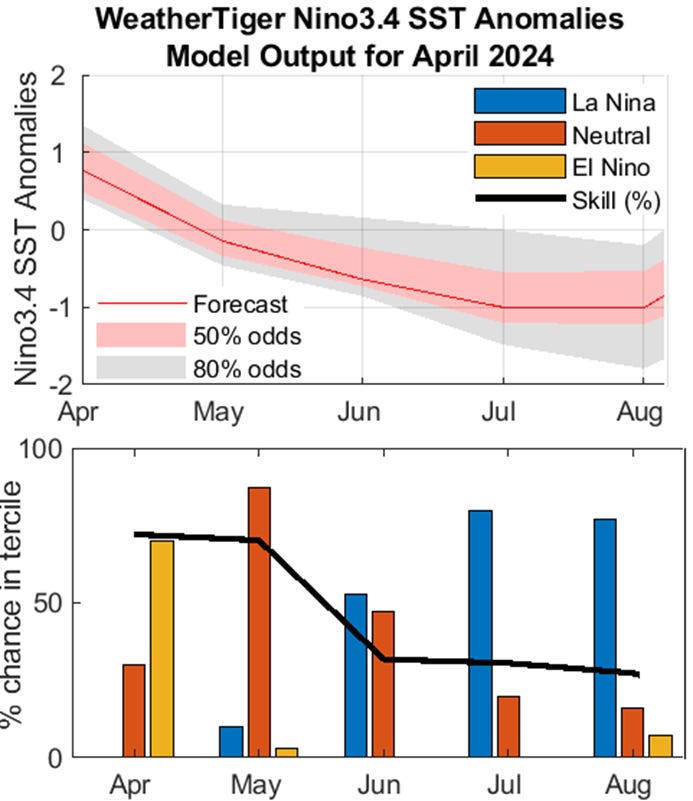

Unfortunately, the 2023-24 El Nino, marked as always by warmer than average SSTs in the Central Equatorial Pacific, is about to fall apart like a paper straw. Beneath a thin pool of warmth lurks a deep reserve of much colder than average waters just waiting for a trade wind surge to reach the surface. This process has already started off the South American coast, leading to a plunge in SST anomalies there. The remnant bulwark of surface warmth in the Central Pacific will be eroded from the east and from below in the next two months, and El Nino should dissipate by WeatherTiger’s next seasonal outlook in late May.

But wait, there’s more. Our internal El Nino/La Nina model and a preponderance of other guidance suggests that the Pacific will proceed straight into La Nina this summer, with an 80% chance of weak or moderate La Nina conditions by the most active months of hurricane season. This would keep upper-level winds favorable for hurricane development in the western Atlantic and Caribbean during August and September. Even if La Nina was slower to develop, the cool-neutral SSTs that likely would characterize the Central Pacific instead also historically favor above-average Atlantic hurricane seasons. With no realistic hope of an early fall El Nino from observations or models, don’t expect a Pacific bailout in 2024.

Get out of the way: Our forecast numbers

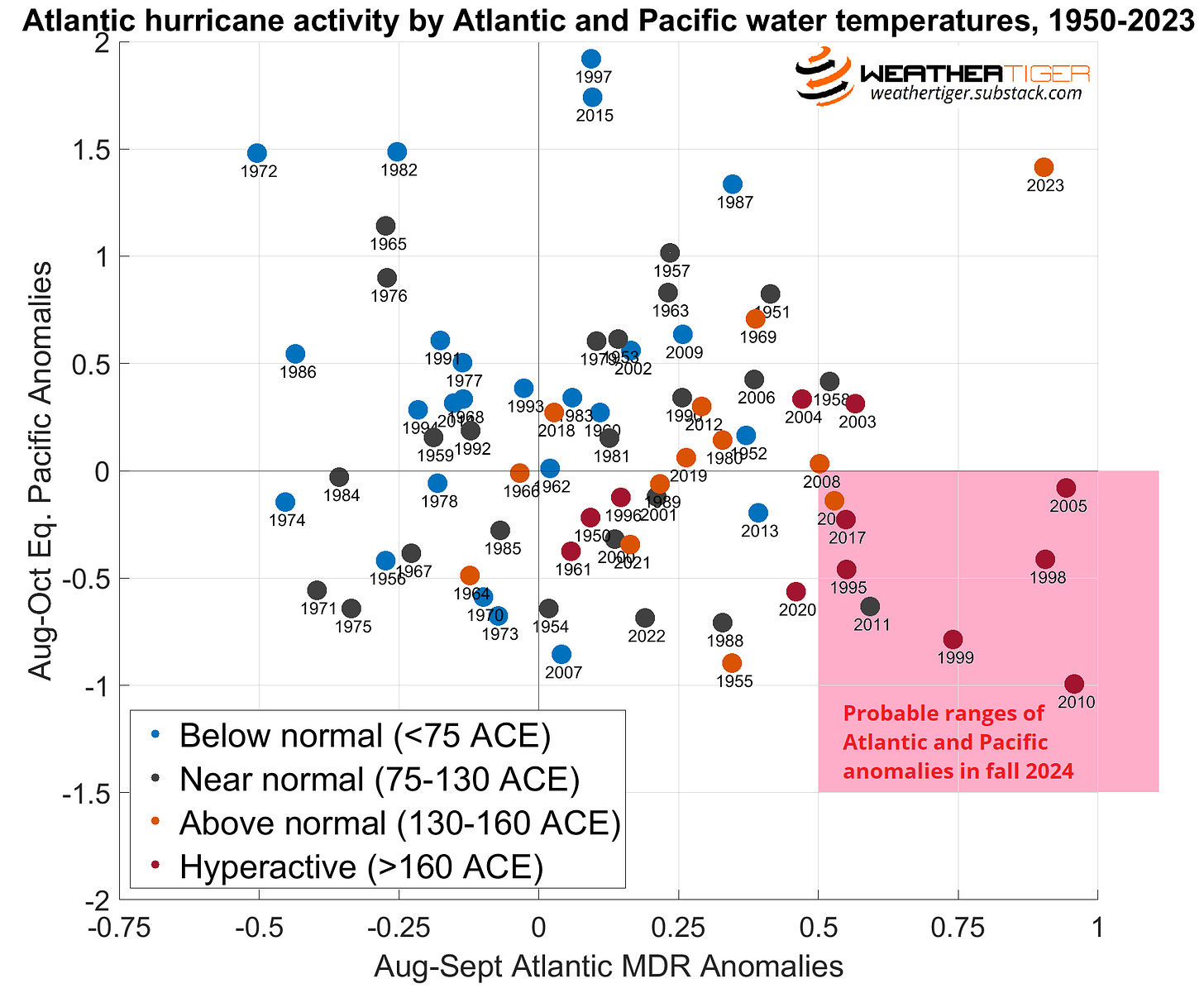

In 2023, forecasters grappled with a dilemma worse than the one faced by Nelly and Kelly Rowland: the two strongest pre-season predictors of hurricane activity were flashing opposite signs for the season ahead. (Check out how extreme of an outlier 2023 is on the chart below!) In contrast, there is high confidence that the Atlantic and Pacific will be rowing in the same direction in 2024, and the core uncertainty is thus whether the upcoming hurricane season will be crazy busy, or merely pretty busy.

Our conservative assumption is that 2024 will join a select group of just eight years since 1950 for which the Pacific is at least a little cooler and the Atlantic MDR at least 0.5°C warmer than average during the peak season. Six of those eight analogous Atlantic hurricane seasons were “hyperactive,” tallying 60 to 150% more total tropical activity than an average year. Some heavy-hitters—1995, 2005, and 2017—are amongst those, alongside other less memorable but still active seasons.

WeatherTiger’s analytical model quantifies these extreme initial conditions, issuing an initial projection of a 75% chance of a hyperactive hurricane season (>160 Accumulated Cyclone Energy units) in 2024 and a most likely outcome of total tropical activity nearly double long-term averages. This corresponds to odds of a normal (75-130 ACE) or above normal (>130 ACE) season of about 10% and 90%, with little chance of a below normal year (<75 ACE). The ’24 season has a 50-50 shot of landing in the ranges of 160-225 ACE, 20-24 tropical storms, 9-12 hurricanes, and 4-7 major hurricanes. Our model boldly suggests a 10-15% chance that 2024 bests 1933’s record for most ACE in a season (258.6), though laying firm probabilities on outliers is a statistical mug’s game. However, our model also does not take into account that unless you are the lead dog, the scenery never changes.

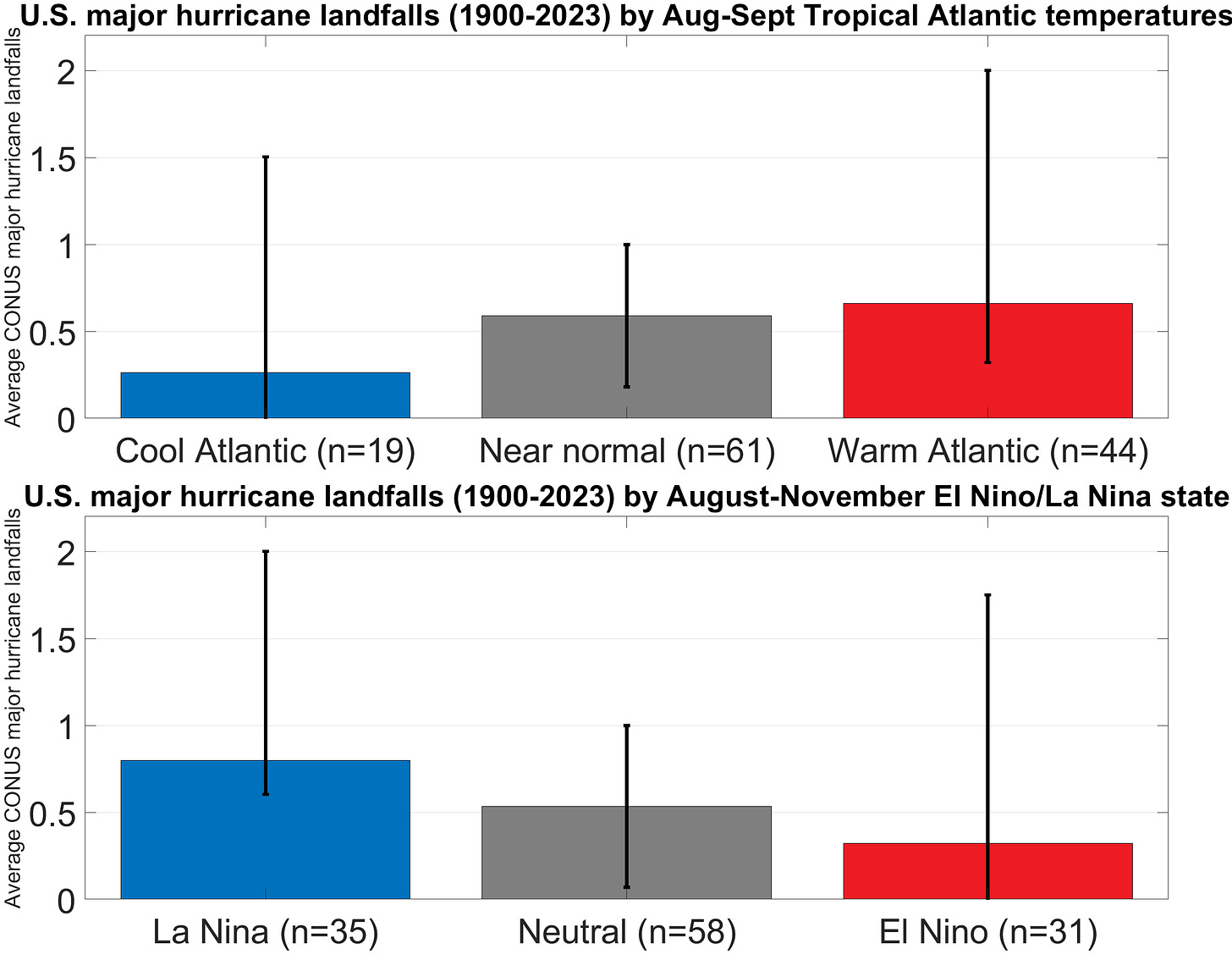

The relationship between net Atlantic hurricane activity and the resulting severity of U.S. impacts is weaker than you might think, but since 1900 U.S. major hurricane landfall risks roughly double between cool Atlantic and warm Atlantic years, and are almost 2.5 times higher in La Nina versus El Nino years. Still, the variability in U.S. landfall outcomes between seasons with similar set-ups can be huge. The best recent matches to 2024 are 1998, 2010, and 2020, each of which saw a peak season La Nina, very warm Tropical Atlantic, and similarly hyperactive total tropical activity. Despite these commonalities, negligible impacts occurred in 2010, four hurricanes but no Category 3’s or above struck in 1998, and 2020 was a wall-to-wall melee of twelve tropical storm, six hurricane, and two major hurricane hits in the continental U.S.

In other words, getting out of 2024 without one or more impactful U.S. hurricane landfalls would be like escaping a Royal Caribbean cruise without contracting norovirus: possible, but not especially likely. With peak season steering currents unknowable at this lead time, WeatherTiger’s landfall risk model predicts a 55% chance that continental U.S. tropical impacts in 2024 land in the upper third of all hurricane seasons since 1900. That’s an elevated risk of U.S. landfalls, but a bit more equivocal an outlook than our overall activity guidance. As Joe Strummer and Natasha Bedingfield said, the future is unwritten. (Paid supporters, a detailed forecast of 2024 U.S. hurricane landfall risk probabilities with exceedance curves is on the other side of the paywall jump for you.)

In summary, much like the “lead, follow, or get out of the way” triptych itself, the 2024 hurricane season is ontologically puzzling and more than vaguely menacing. With Atlantic water temperatures totally off-the-leash and an incoming La Nina refusing to heel, tropical activity may well have that dog in it this year. We’ve got a couple months to go before we start to find out if 2024 will bite or just bark, but given the elevated risks, it is prudent to apply big dog energy to preparing for the hurricane season ahead. Keep watching the skies.

Up and running: U.S. landfall risks forecast

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to WeatherTiger's Hurricane Watch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.