WeatherTiger's Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook for May 2023

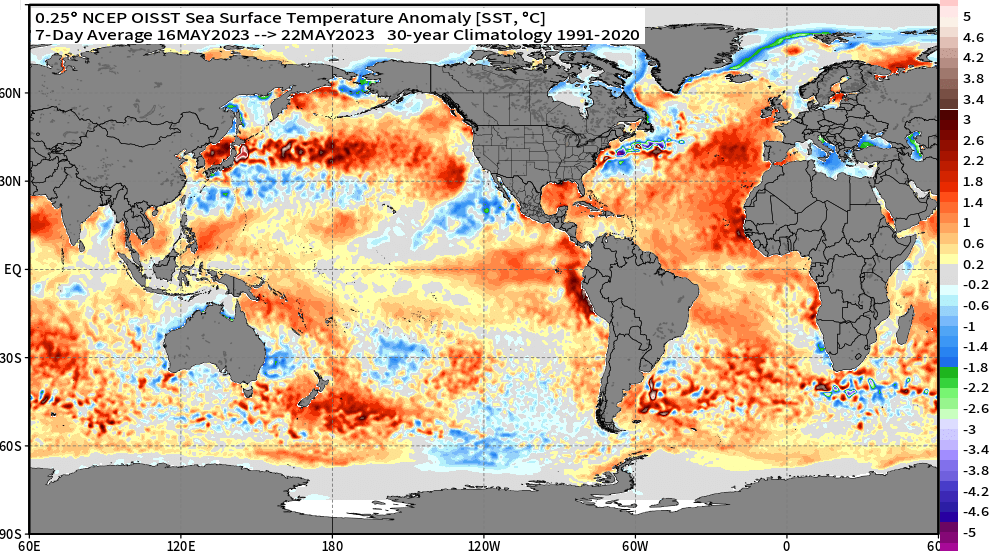

A clash of the titans lies ahead as developing El Niño and notable warmth in the Tropical Atlantic go toe-to-toe.

Here comes the story of the hurricane season: a once-in-a-generation slugfest between twin titans of the Tropics. Live. Six months only. In your backyard, potentially.

In one corner, the Unstoppable Force of an incipient El Niño, maker of coulda-beens out of contender hurricane seasons. In the other, the Immovable Object that is the scorching Tropical Atlantic, packing an explosive thermodynamic punch.

These two atmospheric heavyweights have never been more diametrically opposed entering a hurricane season than in 2023, making for an uncertain seasonal outlook. Fortunately, we have a system: an eye of the Tiger, if you will. WeatherTiger’s seasonal models offer specific odds for overall tropical activity and U.S. landfall risks, and will continuously update those probabilities each day between now and October as punishing blows are exchanged.

More on that later, but first, a little about your humble ringside correspondent: I’m Ryan Truchelut, Chief Meteorologist at WeatherTiger, a weather analytics and forensic meteorology firm. I have a doctorate from Florida State and almost 20 years of professional hurricane forecasting and research under my belt. I’ve been providing tropical analysis and dad humor here at WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch for three years. Expect a column each Monday through October, with more frequent forecasts as the situation warrants. Also, note that I’m an avid runner with zero boxing knowledge, though if I had the opportunity to name a subdivision street, I would call it Judgemills Lane.

Without further ado, let’s get ready to rumble. Meteorologically speaking.

The Contenders

El Niño

Nicknames: Pacific Pugilist, Shear Annihilation, The Southern Oscillation Dandy, The Mandatory Farley Reference

The Vitals: El Niño is the warmer half of a cycle known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Key Niño features include sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Central Equatorial Pacific of more than 0.5°C above normal and an interlocking regime of weaker trade winds and increased convection in the same area. Once this feedback cycle begins, El Niños usually persist for around a year.

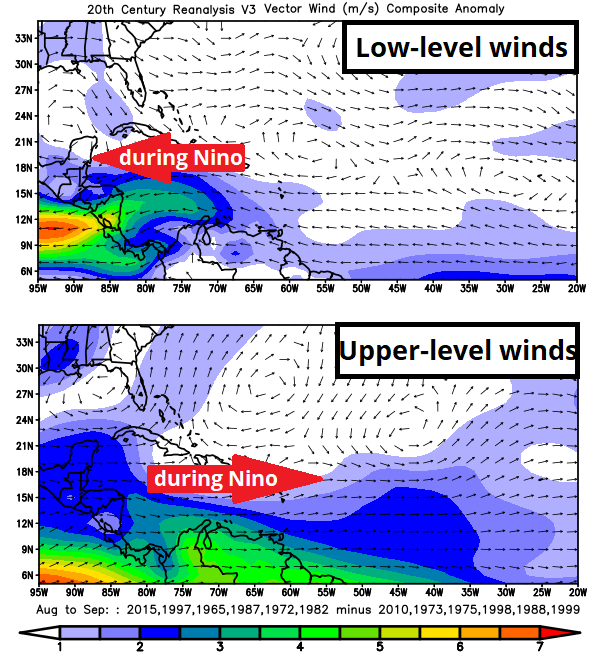

ENSO matters for Atlantic hurricane seasons because a rollicking El Niño or La Niña modulates weather patterns worldwide. In the peak of El Niño hurricane seasons, low-level winds in the Tropical Atlantic blow faster from east-to-west than during La Niñas. The opposite is true at the upper levels of the atmosphere, with stronger winds out of the west during Niños, especially in the Caribbean and southern Gulf. Thus, persistent wind shear, or wind strength and direction changes with height, is a signature of an established El Niño. Shear exceeding about 30 knots is highly unfavorable for hurricane development, capable of chumping even the most formidable tropical waves.

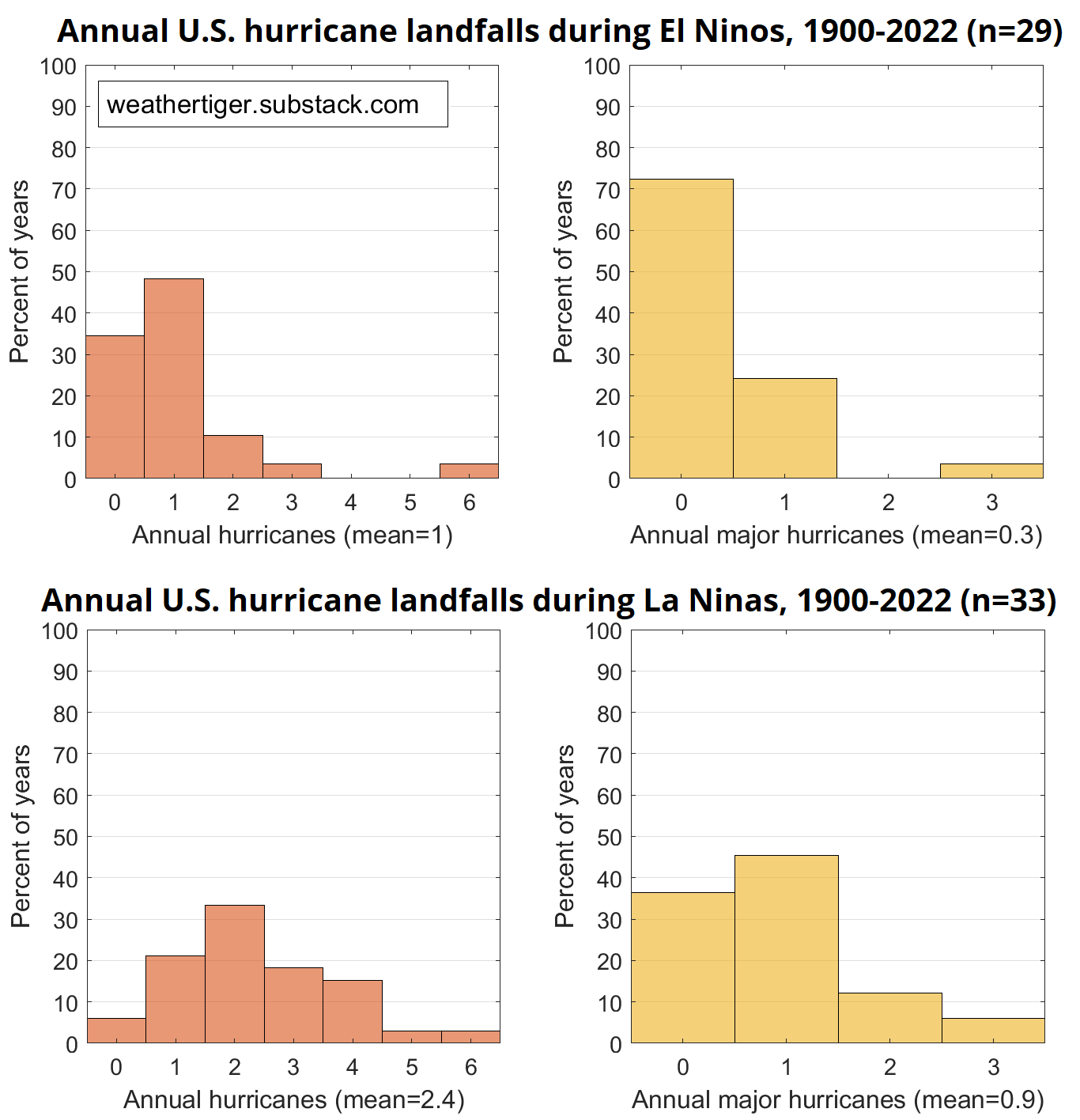

The Record: El Niño is the single strongest pre-season predictor of U.S. landfall activity. About one-quarter of hurricane seasons occur during Niños; in these years, there is only a 65% chance of at least one continental U.S. hurricane landfall, and a little less than a 30% chance of a major hurricane landfall. That is significantly less than the 90%+ chance of one or more U.S. hurricane landfalls and 65% probability of a major hurricane landfall during La Niñas.

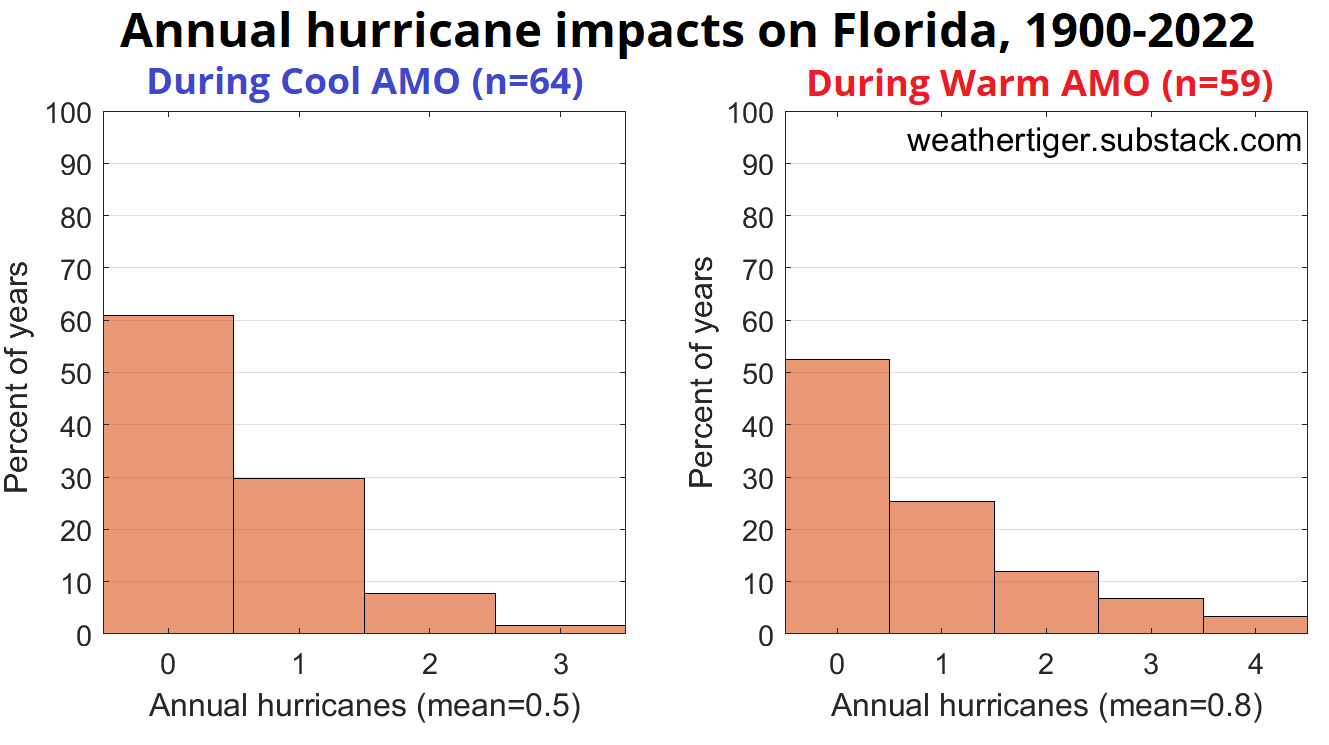

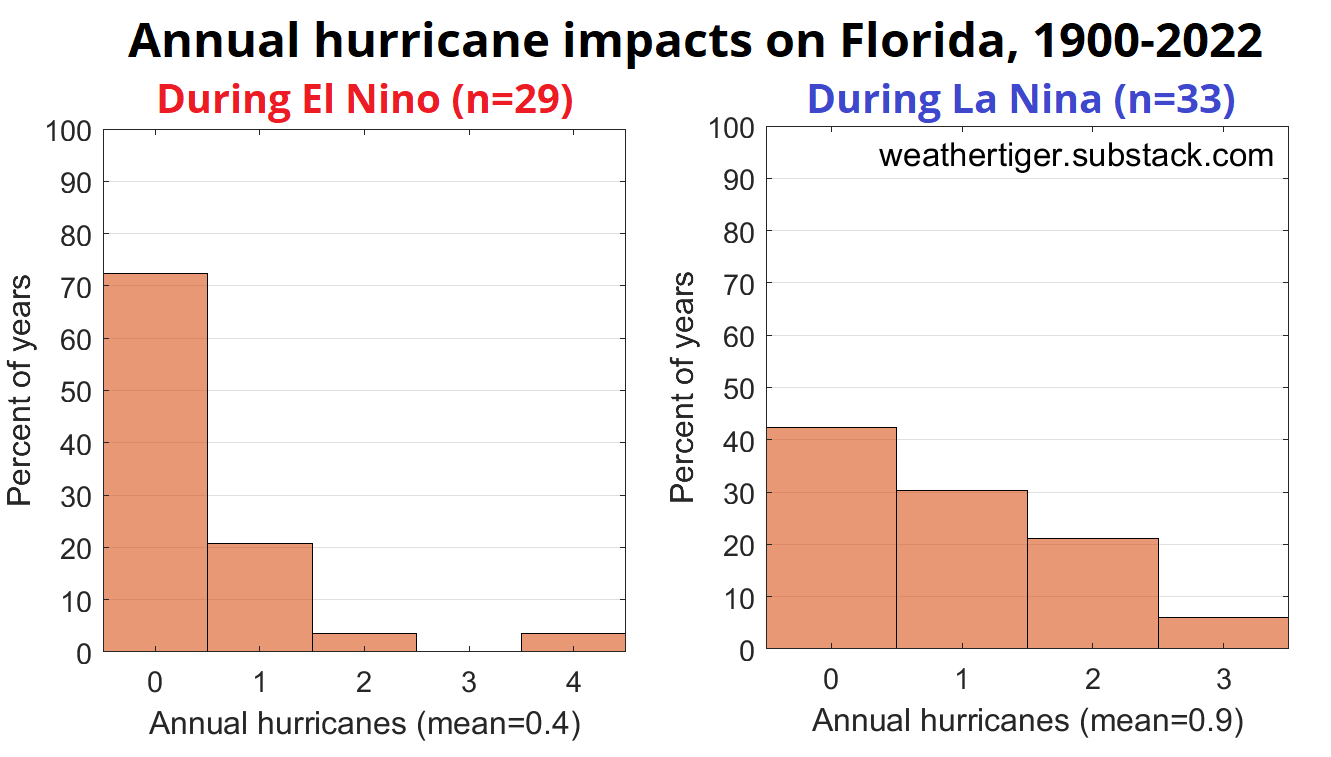

This relationship holds true in Florida as well, with odds of at least 1 Florida hurricane plunging from nearly 60% to around 25% moving from La Niña to El Niño conditions. The average number of Florida hurricane impacts in El Niño years is less than half that of La Niñas.

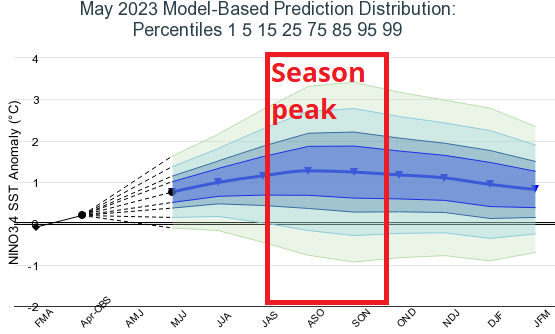

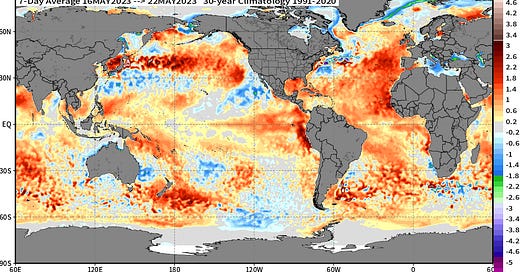

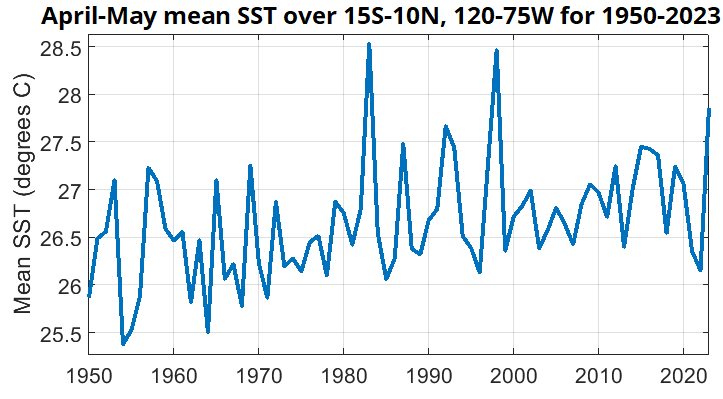

The Weigh-in: El Niño is a hungry young fighter as the 2023 hurricane season approaches. While SST anomalies in the Central Pacific are just now crossing the +0.5°C ENSO threshold, ocean temperatures in the Eastern Pacific often prefiguring Niño strength are already the third-warmest since 1950. This year’s SSTs in the east trail only the monster El Niños of 1983 and 1997.

The rapid transition out of last winter’s La Niña, impressive subsurface warmth, and a strong model consensus all indicate that the 2023 El Niño is most likely to see SST anomalies between +1.0 and +1.5°C during the peak of hurricane season— setting up a potential haymaker to storms transiting the southern Gulf or Caribbean.

Yet as much as we’d like to, we can’t throw in the towel on the 2023 season. A challenger arises.

The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation

Nicknames: The Sargassum Scalder, Ruinous "Hurricane" Starter, The Property Insurance Crisis Kid

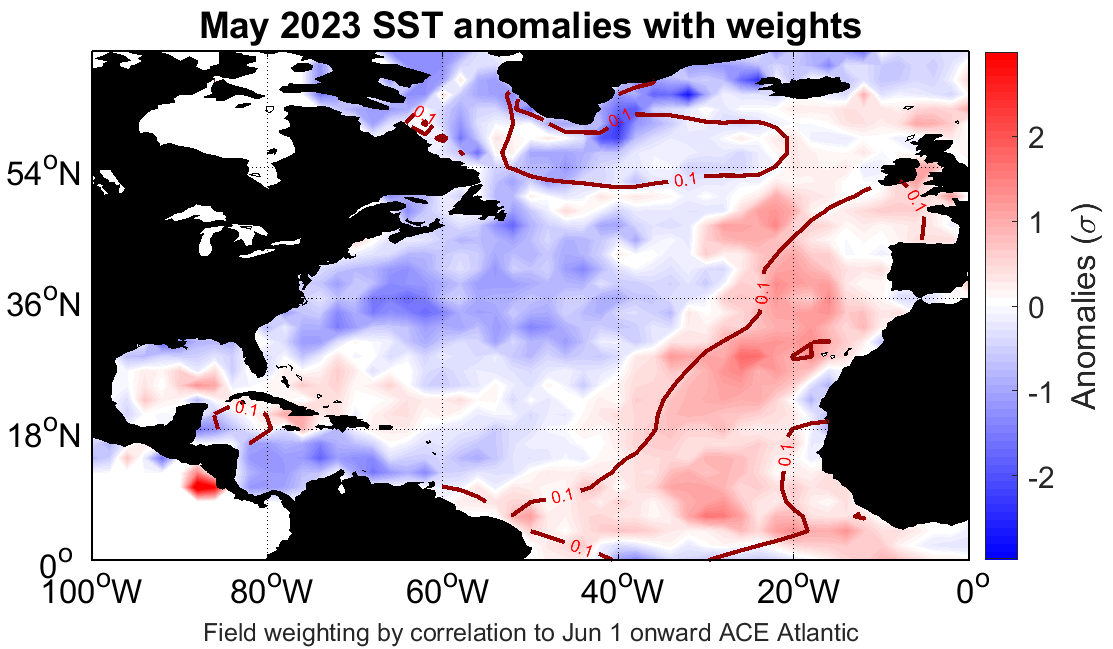

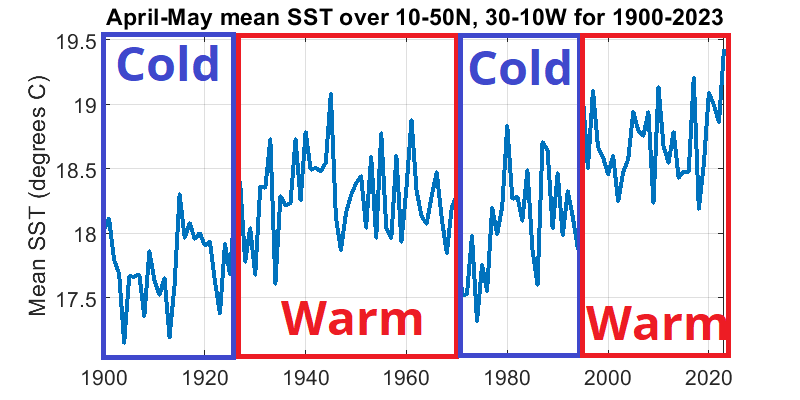

The Vitals: The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, or AMO, is a purported natural cycle in which Tropical Atlantic SSTs alternate between 20- to 50-year colder and warmer periods (future column alert for an AMO Eras tour). During warm AMO phases, like the one that began in 1995, SSTs are generally above normal in the Main Development Region of the Tropical Atlantic and a crescent of the eastern Atlantic extending north to Iceland.

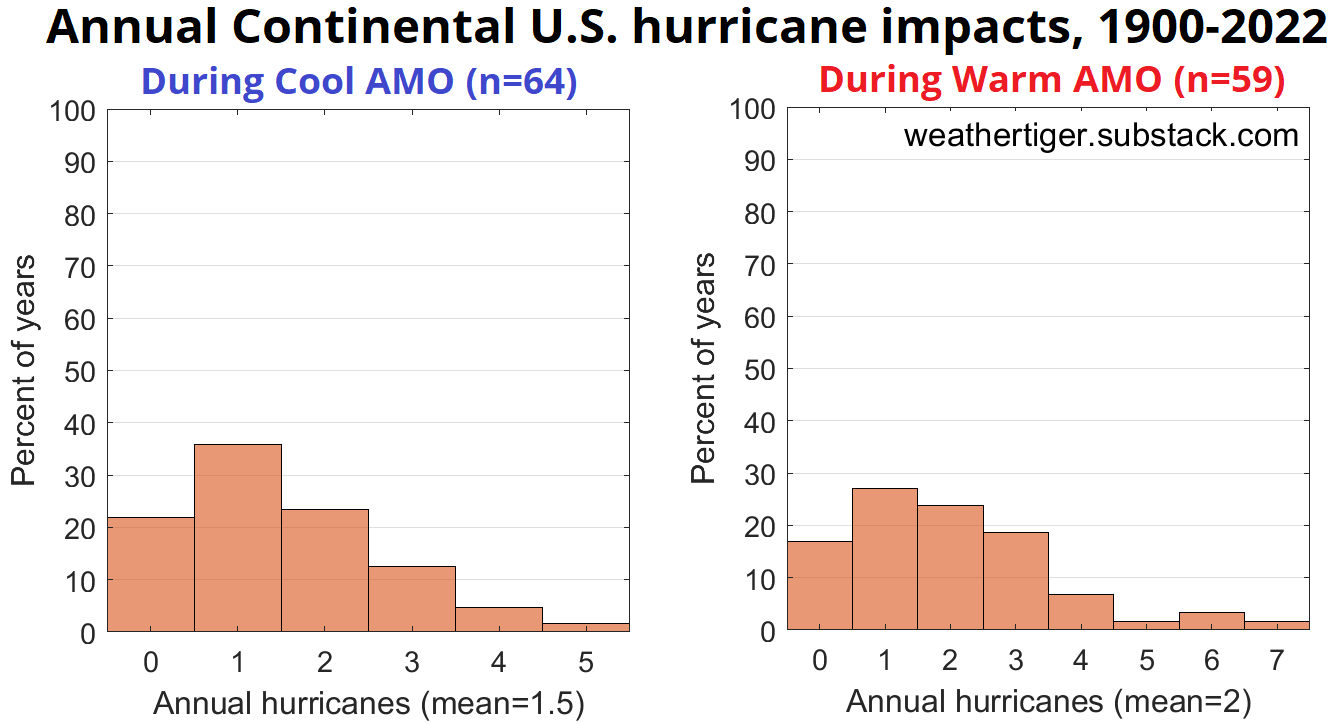

The Record: The AMO doesn’t have quite the dominance of ENSO, as Atlantic warmth can ebb and flow on short notice in a way that a mature El Niño does not. However, warm AMO regimes still have considerably higher hurricane risks in both the continental U.S. and Florida. The average number of annual U.S. hurricane impacts is about 35% higher during a warm AMO than a cool AMO, and around 60% higher in Florida.

The Weigh-in: Warm AMO is flying high now. In fact, SSTs in the linchpin regions of the eastern Atlantic are nearly half a degree warmer than previous records and rising. These warm SST anomalies also closely conform to the regions where May ocean temperatures have the strongest historical relationship with busy hurricane seasons. In the absence of an onrushing El Niño, this pattern and its extreme amplitude would be extraordinarily alarming. As is, it sets up ENSO vs. AMO: Tropic Thunder.

Laying odds

Every hurricane forecaster has a plan until they get punched in the mouth. This year’s punch is that the two most reliable pre-season predictors are more divergent than they ever have been heading into the season.

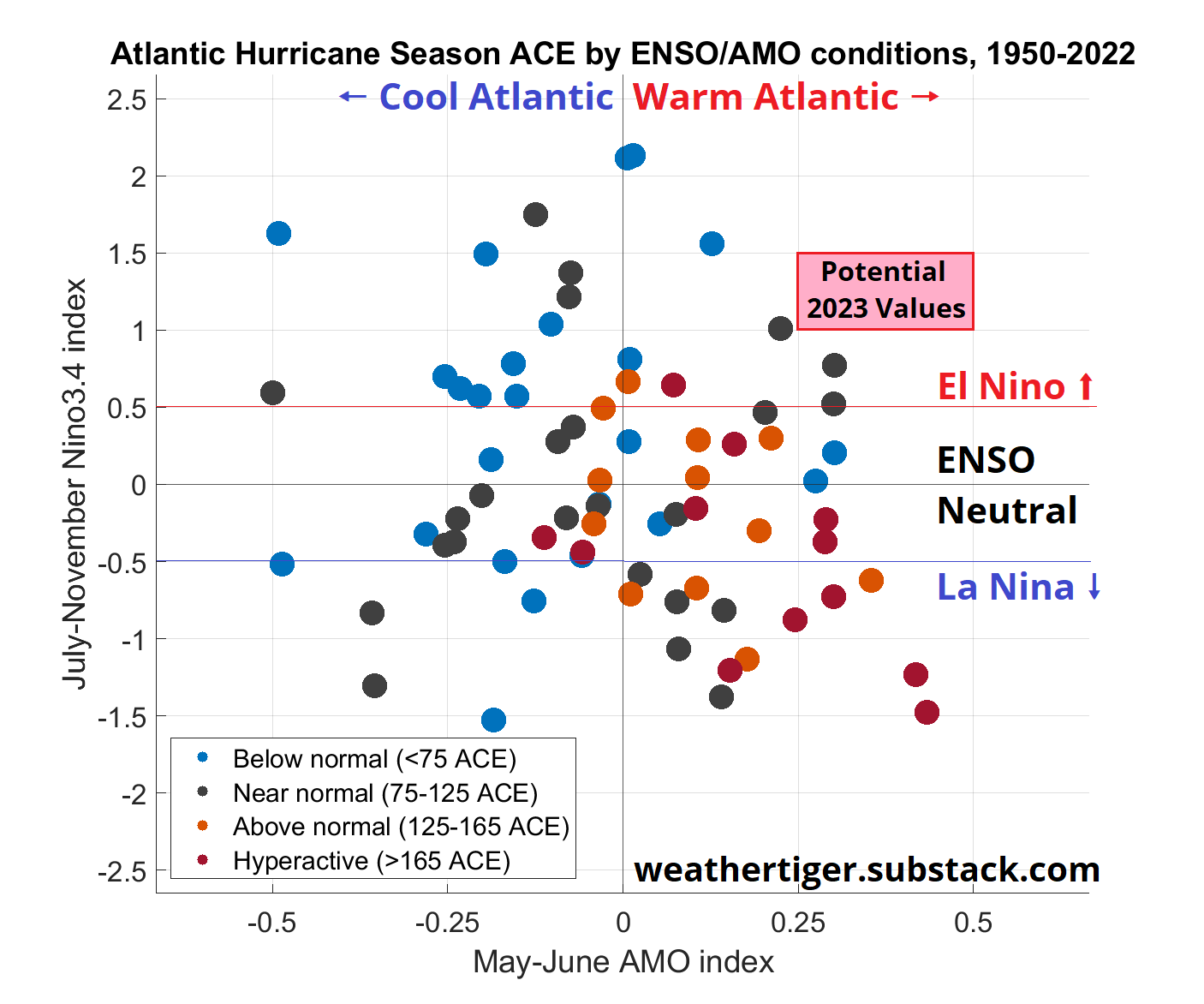

Looking at seasonal outcomes as a function of both early summer AMO and peak season ENSO, above average or hyperactive hurricane seasons (red and orange dots) happen when neutral/warm AMO and neutral/La Niña ENSO conditions are occurring simultaneously. While ENSO and AMO are semi-independent of one another, they are almost never completely in-phase. Since 1950, there are only three other seasons with the May-June AMO index exceeding +0.2 and an active El Niño during peak season. As shown by the light red box, expected AMO and ENSO values for 2023 are quite likely to be warmer on both counts than these loose analogs (1951, 1953, and 2006), all of which were near normal seasons.

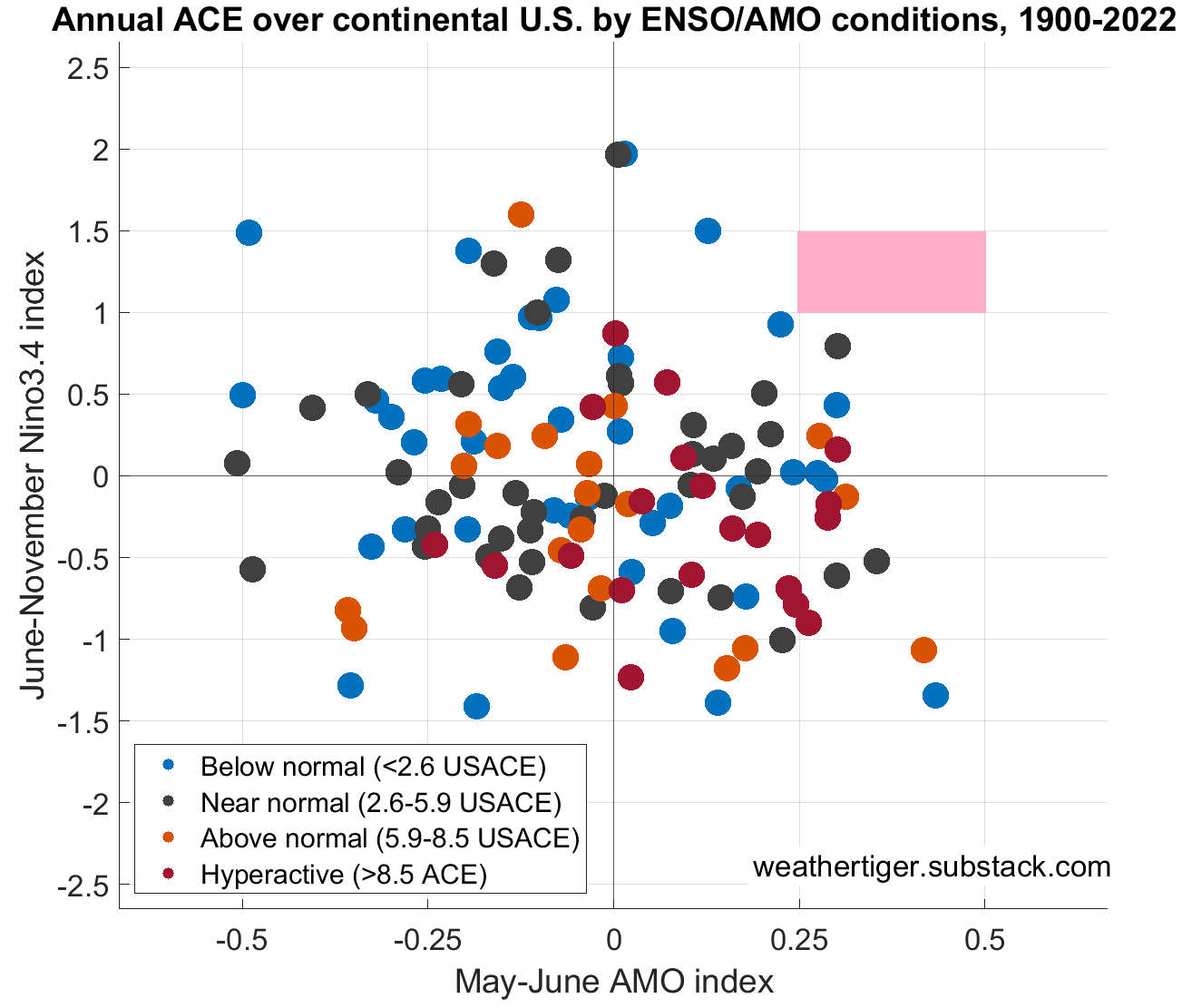

Nor does expanding horizons back to U.S. landfall activity since 1900 offer much help. While hyperactive U.S. landfall seasons (red dots) still cluster in the lower-right (warm AMO, La Niña) quadrant, our expected values for 2023 continue to land on the “here be dragons” portion of the map. Thus, analog-based forecasting methods are of limited value for the upcoming season. There simply are not solid historical parallels.

Fortunately, WeatherTiger’s seasonal models have been hitting the stadium steps and slamming raw eggs in the off-season, preparing for just such a prizefight. Our upgraded methodology for 2023 considers a broader and more optimized array of predictors than before, capturing not only how the Atlantic and Pacific are currently, but various scenarios for how they might evolve into the peak of the season.

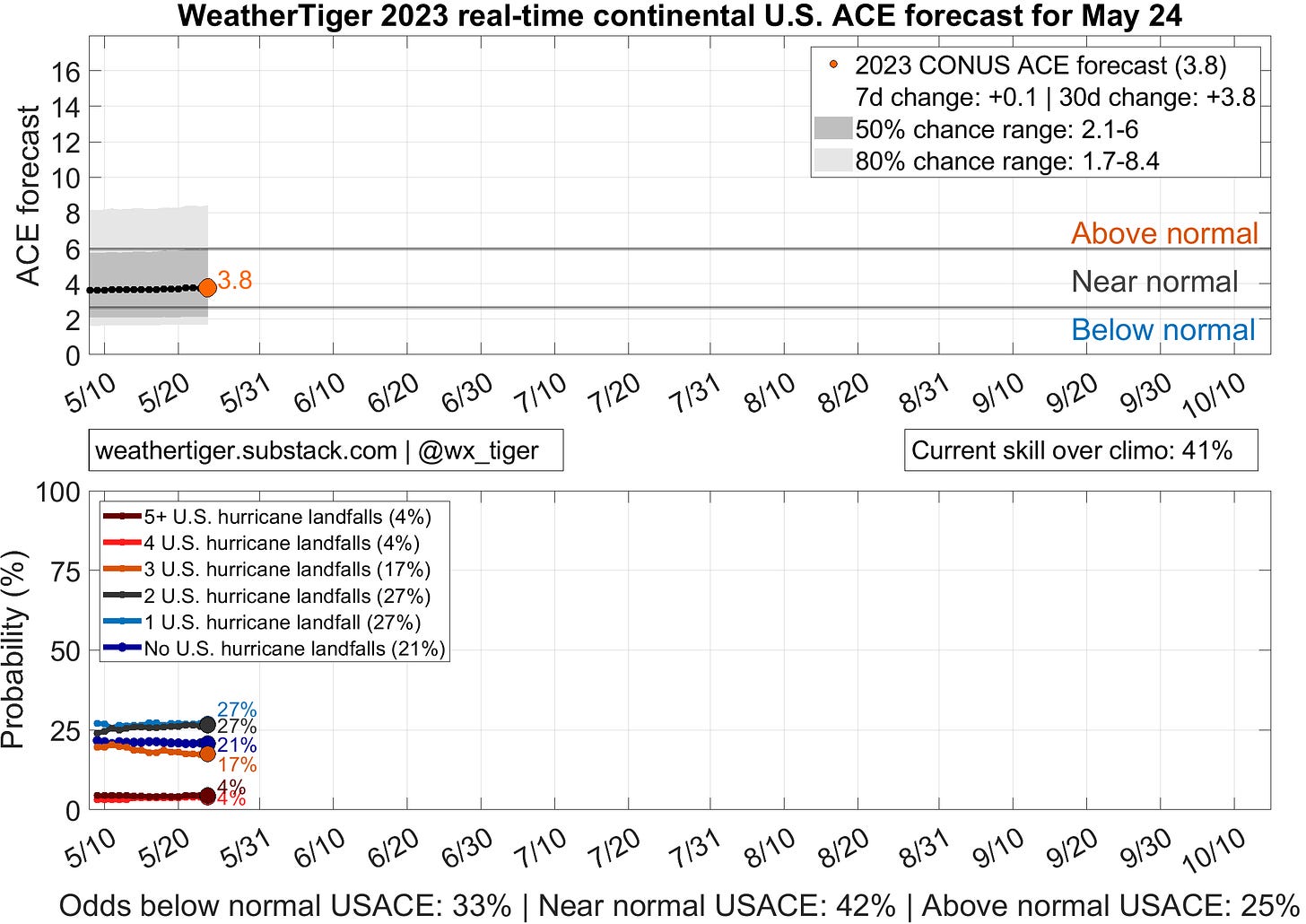

With ENSO and AMO in an even more liminal state than Florida itself, our model’s true power this year is its unique real-time capability. Each day between now and October, WeatherTiger’s algorithm will digest an updated snapshot of the ocean and atmosphere, and intelligently translate that tsunami of raw data into fresh odds of how Hurricane Season 2023 is most likely to play out. Check out updated daily predictions here.

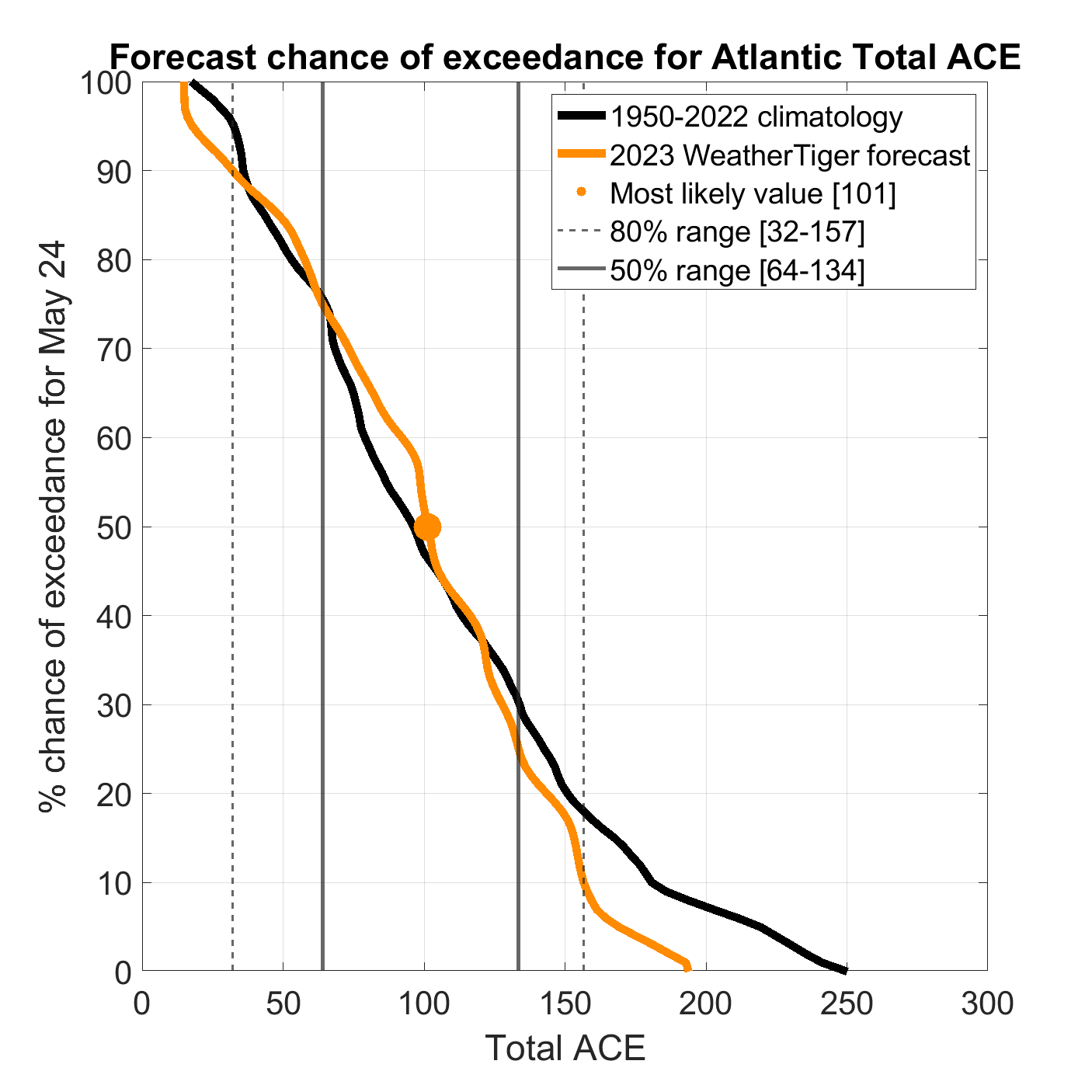

Will 2023 float like a butterfly or sting like a bee? It might do a little of both, with ENSO and AMO most likely fighting to a draw. The odds of a below normal, near normal, above normal, and hyperactive hurricane season, respectively, are about 30%, 40%, 25%, and 5%. WeatherTiger’s model is bearish on the potential for a hyperactive season, which would be tough to accomplish with the Caribbean and southern Gulf getting roundhoused by wind shear.

Still, unfavorable conditions there don’t preclude U.S. landfalls, our primary concern. This year, WeatherTiger is debuting a seasonal model tuned to predict the net tropical activity occurring near or over the continental U.S. This model is calling for U.S. landfall risks close to long-term averages, with around a 45% chance of U.S. tropical activity coming in close to normal. That translates into a 25% chance of three or more hurricane impacts, a 55% chance of 1 or 2 impacts, and a 20% chance that the continental U.S. escapes 2023 without a hurricane encounter.

It also suggests around a 40% chance of at least one major hurricane impacting the continental U.S., which is higher than the baseline 30% chance during an El Niño, likely due to the influence of the warm AMO. Our U.S. landfall risk model is also running in real-time starting today as a supporter exclusive, which you can follow here; paid subscribers can also access Florida-specific seasonal landfall odds at the end of this outlook behind a paywall.

Ringing the Bell

As the Atlantic and Pacific heat up like a George Foreman Grill or Manny Pacquiao Signature Panini Press, the purported normalcy of the 2023 Hurricane Season may well be the average of long stretches of boredom punctuated by moments of terror. Qualitatively, I think it is quite likely that a top 10 El Niño is forming, which is going to put a kibosh on Caribbean activity no matter how warm the water is there. That may mean a busier first half of hurricane season and a quieter October.

On the other hand, extreme warmth in the eastern and subtropical Atlantic, where the reach of ENSO is weaker, augurs a busier year than is typical of El Niños. WeatherTiger’s daily model output is shifting in a bit more active direction as the season approaches, perhaps recognizing an incoming split decision.

As a final caveat, “near normal” hurricane seasons contain the multitudes. Last year ended close to historical averages for overall activity, yet landed a $113 billion knockout punch. As vast swaths of the Gulf Coast carry the reminders of every glove that laid us down, remember that the only way to be hit and hit back, a.k.a. the name of the game, is to make a hurricane plan before storms threaten. In the meantime, here’s hoping for a respite from needing to activate those plans in the season ahead: I’ll be watching, blow-by-blow. Keep watching the skies.

Pay-per-view: Florida landfall odds (supporter exclusive)

Greeting, subscribers! As always I appreciate everything you do to make this newsletter possible. As WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch continues to grow, I am looking for new ways to add value for you, so don’t hesitate to drop me a line at ryan@weathertiger.com or to get in touch via Substack Chat or Notes with feedback.

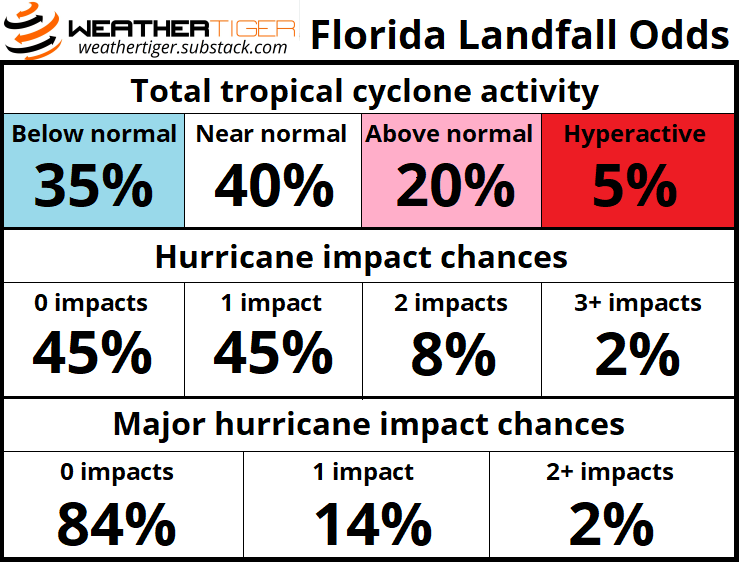

One change in 2023 is going to be the addition of subscriber bonus content at the end of the weekly columns. (Maybe not every week, but at least half.) Today’s bonus is a look at the output from an experimental variant of our landfall model focused only on tropical activity over or near (within 50km) of Florida.

This model isn’t quite ready for the real-time treatment, but I will be updating it a few times through the year, and perhaps even upgrading and/or adding additional zones as we go. No specific promises, other than to keep you posted.

In any case, WeatherTiger’s modeled Florida landfall probabilities for 2023 are in some ways optimistic, and others not so much. The categorical landfall odds are similar to those for the U.S. as a whole, perhaps just a touch less active. One bright spot is that the chances of a Florida major hurricane impact are about 1-in-7 in 2023 compared to about 1-in-4 in an average year. Not impossible, but less likely than not.

On the other hand, this experimental model does not want to give Florida the year off. The chance of no hurricane impact anywhere in Florida this year is a little less than 50%, compared with a baseline of 57%. Conversely, the odds of 1 impact somewhere in the state are also a little less than 50%, versus about 30% historically. Two or more hurricane impacts come in at around a 1-in-10 chance this year against a 1-in-6 chance in climatology.

It’ll be interesting to see how this experimental model performs this year. Don’t forget that paid subscribers can exclusively monitor daily updates of U.S. landfall probabilities at our 2023 real-time modeling page.

Thanks so much. We used to have a home on Cape San Blas and "yes" the bad weather used to always hit us there. THANKS FOR ALL YOU DO!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Hoping your info and forecasts show Naples area specially ….Really like your approach and ability to simplify so we understand!!

Dan Gillen