Regressions, Part II: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for August 10th

In Part II of WeatherTiger's seasonal outlook, digging into how steering currents may shape up for the peak of hurricane season.

If you enjoy this outlook, consider supporting WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch by signing up for our comprehensive coverage of what looks to be a busy 2022 season. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, weekly columns, full forecasts of every U.S. hurricane threat, and our real-time seasonal hurricane outlook for $7.99/month or $49.99/year.

From the heart (and no, I am not referring to Hard Equations And Rational Thinking), I believe August to be the worst month of the year. Heckish heat and sauna humidity continues, despite the good part of summer, in which creating small, colorful explosions in the sky is socially acceptable, being long past. Kids are making grim countdown calendars for the 288 days until summer vacation; the rest of us reckon with a dispiriting 112 days left in hurricane season.

From the tropical perspective, August is not the absolute worst, but it certainly is the on-ramp to the most dangerous portion of the season. About 25% of continental U.S. landfall activity occurs in August, second to the 45% or so that takes place in September. So far, the U.S. has been unscathed, and there are no threats over the next seven to ten days. The only tropical disturbance worth noting is a tropical wave in the eastern Atlantic struggling mightily against a bone-dry airmass. Even on the off chance this wave slowly develops, steering currents will hustle it out to sea early next week.

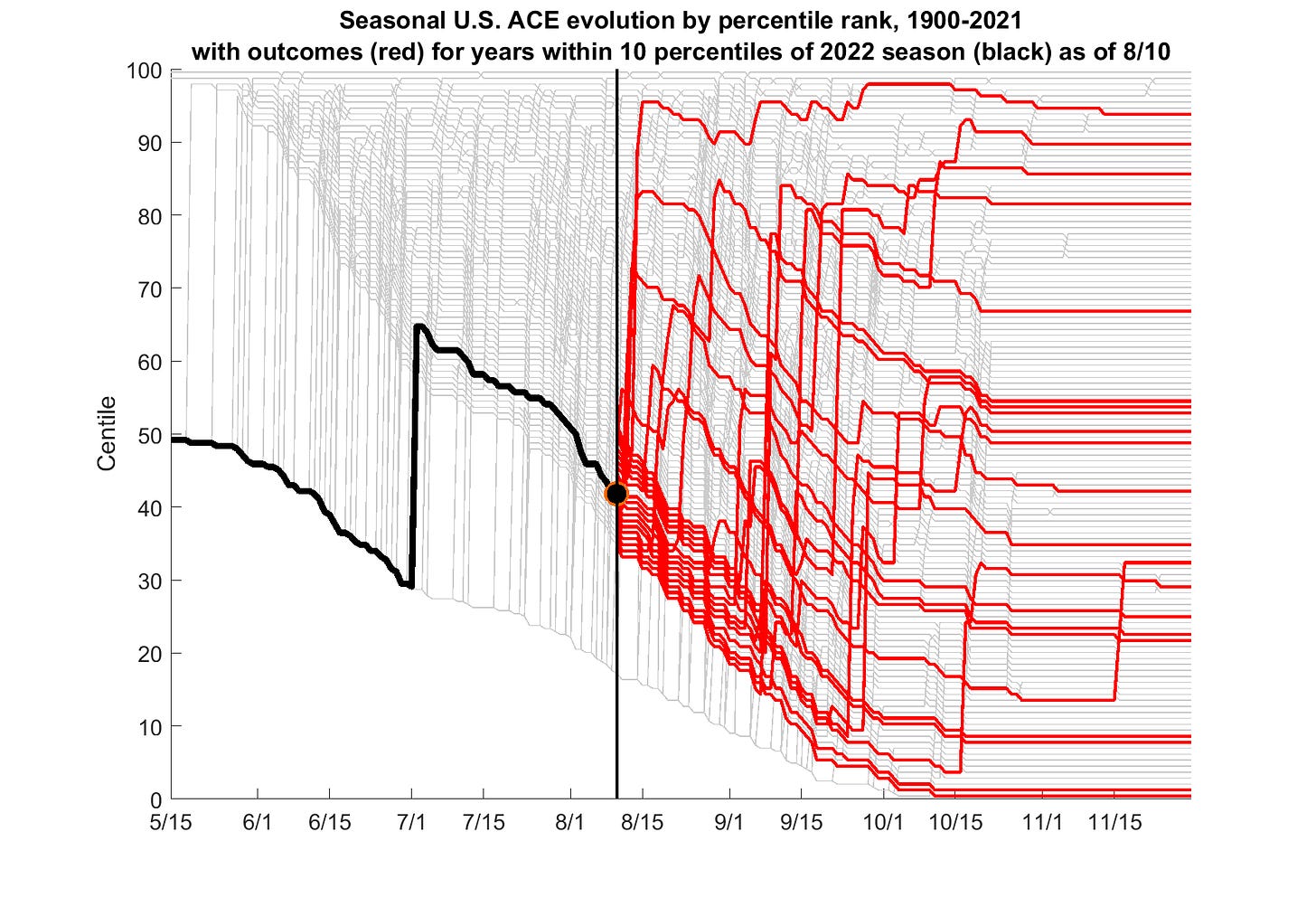

That slow start doesn’t mean much. Of the historical hurricane seasons best matching 2022’s leisurely pace, half of them finished above and half below the normal level of U.S. landfalls for the full year. Much more meaningful are the predictors like La Niña and Tropical Atlantic ocean temperatures that I discussed in WeatherTiger’s updated season outlook last week, which continue to point to net Atlantic hurricane activity about 50% higher than the average since 1970.

Of course, where those hurricanes develop and track is important, as similarly active years can have wildly divergent impacts. In 2004, nine Atlantic hurricanes led to six U.S. hurricane landfalls and $60 billion in damage. In 2010, twelve Atlantic hurricanes caused zero U.S. landfalls and less than $250 million in losses. No one sits around the campfire and recounts the legends of the 2010 hurricane season.

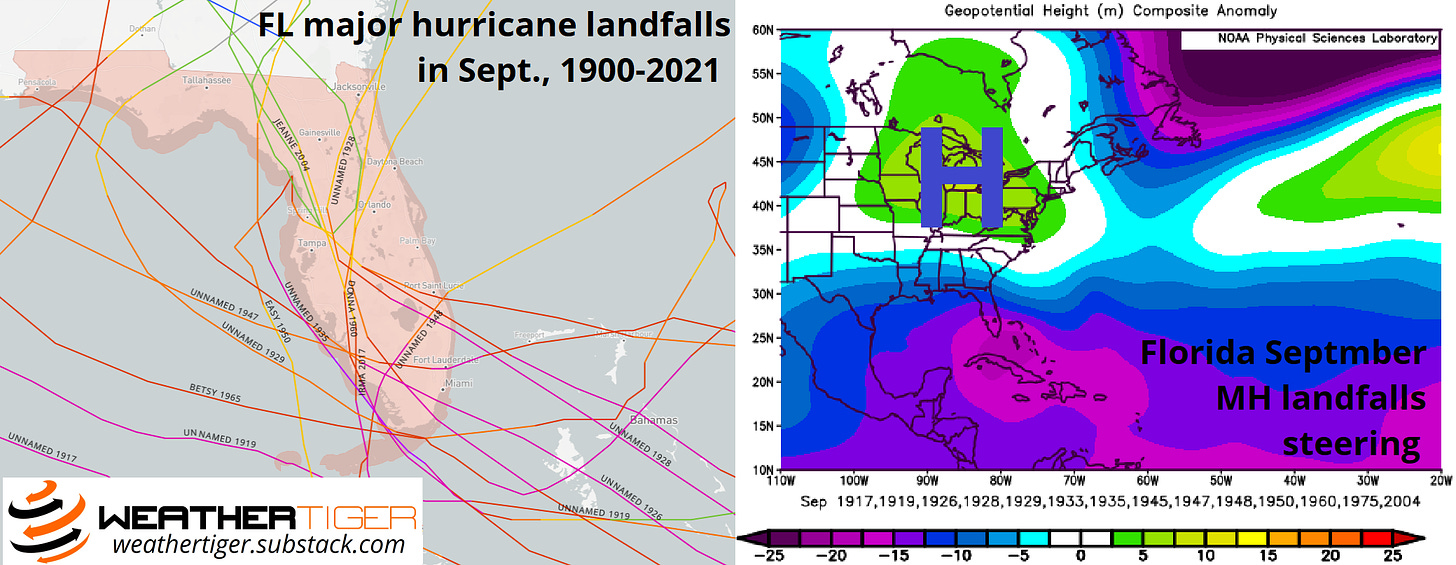

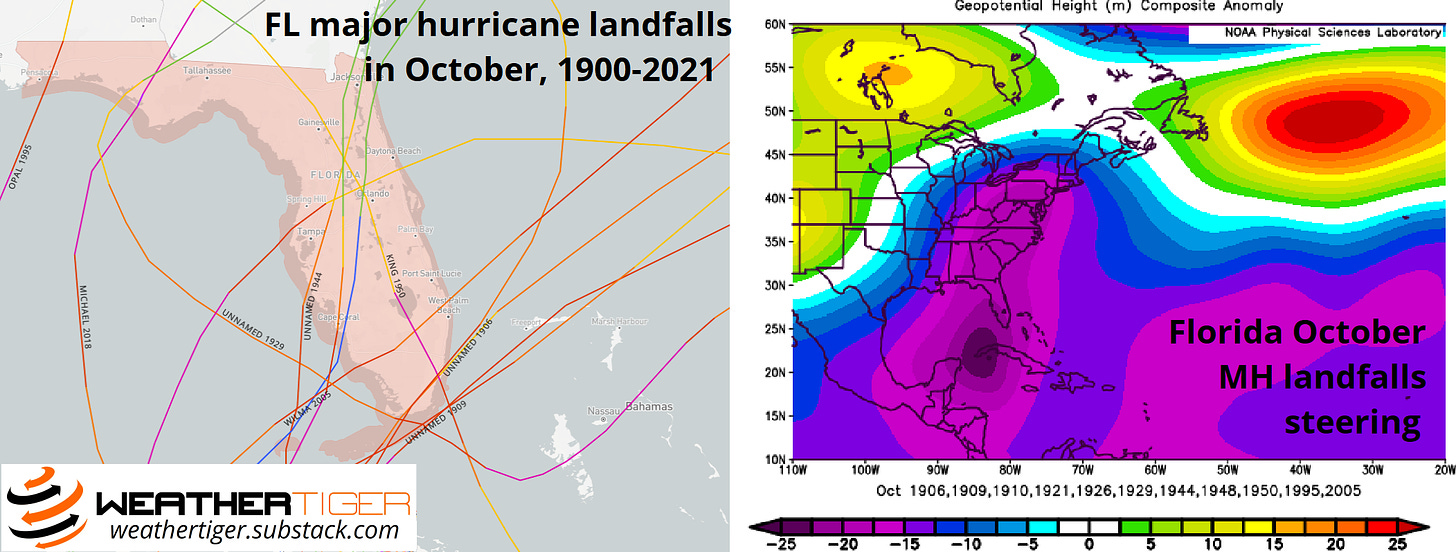

What makes for a dangerous steering current regime? For Florida’s two busiest months, the average locations of high pressure ridges and low pressure troughs for years in which major hurricanes struck the state tell the tale. In the 16 Septembers since 1900 with a major hurricane landfall in Florida, there is an increased tendency for strong, persistent high-pressure systems aloft to set up over the Great Lakes and Eastern Seaboard. The clockwise windflow around this “blocking” high pressure ridge steers hurricanes developing in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region west-northwest across the state and prevents northward turns east of Florida.

In October, the favorable pattern is just the opposite. The 12 Octobers since 1900 with Florida major hurricane strikes have a tendency for more high-pressure blocks in eastern Canada, the southwestern U.S., and the north-central Atlantic, favoring upper level troughs over the Midwest and eastern U.S. to steer hurricanes north out of the Caribbean and toward the Gulf Coast.

There are a couple of sea surface temperature configurations that make the development of these two distinct blocking regimes more or less likely. El Niño and La Niña certainly play a role, while other mid-latitude climate modes like the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), a pattern of ocean temperature anomalies in the northeast Pacific, also have a key influence.

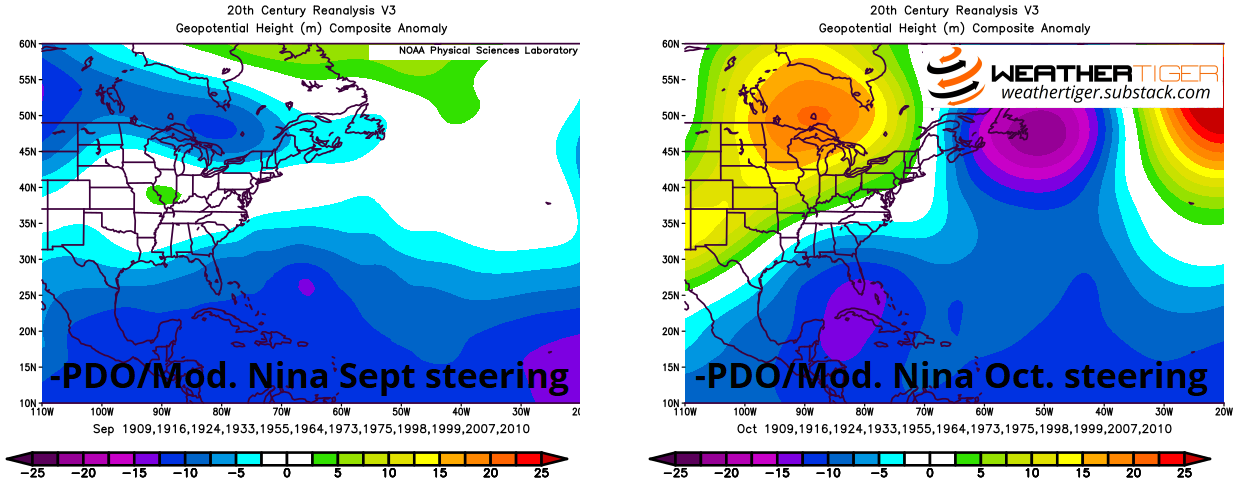

If you read my dissertation (note: do not do this), you’ll find that phases of the PDO in which the coastal waters off the U.S. and Canadian west coasts are cooler than normal, as they were through much of summer 2022, make eastern U.S. blocking ridges less likely. And, indeed, the Septembers with moderate La Niñas (like 2022) and cold phase PDO tend to have a steering pattern close to the opposite of Florida landfall years, with troughing over the east-central U.S. offering an open ocean escape route for Cape Verde hurricanes.

However, moderate La Niña and cool PDO Octobers do tend to see blocking develop over Canada and the southwestern U.S. In fact, the composite of historical moderate La Niña and cool PDO Octobers is a very good match for the steering currents observed in years in which Florida experienced a major hurricane in October, with similar positioning of ridging and troughs.

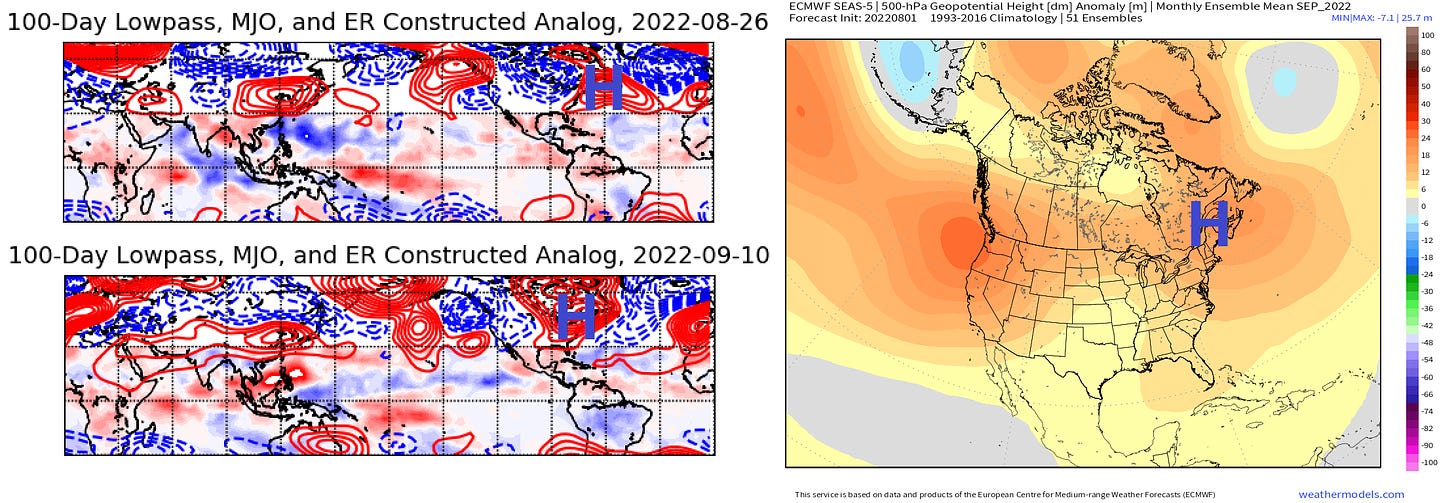

The twist in 2022 is that while La Niña and cool phase PDO tend to go hand in hand, the formerly colder than average ocean temperatures in the coastal northeastern Pacific have warmed considerably in the last few weeks, and the PDO has recently taken on a bit more neutral look at the moment. A northwestern U.S. heat wave through mid-August may further reinforce this trend. Should cool phase PDO be waylaid in September, all else equal, this could indicate higher chances of more persistent eastern U.S. blocking during the peak of the season.

Some analog and long-range modeling indicates that blocking may start to develop over the western Atlantic in the last week of August, and blossom over the Great Lakes through the first half of September. This would be a worrisome steering pattern for the historically most active weeks of hurricane season, should it indeed develop.

Of course, steering patterns are literally capricious zephyrs, and landfall risk outlooks have modest historical skill. WeatherTiger’s predictive algorithm projects around 6 units of ACE to occur over the continental U.S. during the remainder of the season. A normal year would have about 4 more units of U.S. ACE after mid-August.

That means landfall risks are above normal for Florida over the next few months, and there are some shadows on the cave wall favoring a worrisome steering regime in September. As ever, it would be surprising to get through the next 10 weeks without at least some major tropical intrigue for Florida or the rest of the continental U.S.

So, be prepared for whiplash when the quiet regime ends, and don’t be shocked if August plays to its demotivational strengths by the end of the month. However, there’s nothing tropical to worry about in the near future, so like a cat clinging to a laundry line, hang in there, baby, and keep watching the skies.