WeatherTiger's Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook for August 2023

The Atlantic and Pacific continue to suggest very different outcomes for the season ahead.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused tropical briefings each weekday, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

Part I: Overall Activity

Originally published August 1, 2023.

August always arrives with a whiff of impending disaster. Fourth-graders who have eschewed summer reading in favor of Roblox must hastily identify the setting and main characters of The Giver by Lois Lowry. Miami Dolphins fans attempt to stay positive while knowing yet another eight-win season lies ahead. Many are once again completely unprepared for the existential terror of National Clown Month.

And of course, we all must reckon with the imminent, savage heart of hurricane season.

Like the setting of The Giver, recent hurricane season peaks have been downright dystopian. Six Category 4 or higher landfalls have overwhelmed the Gulf Coast over the last seven years; all six struck between late August and early October, the chaotic two-month period into which two-thirds of historical U.S. landfall activity is crammed. All told, the last three years have brought a numbing 26 total named storm and 11 hurricane landfalls, tallying $235 billion in U.S. damages.

So far, the 2023 season has been a nice reprieve, at least in terms of U.S. impacts. While there have already been five named storms racking up about three times normal activity to-date, these systems have had the uncommon decency to avoid the U.S. coastline. That’s fortunate indeed, as about 60% of seasons have a U.S. impact from a tropical storm or hurricane before August.

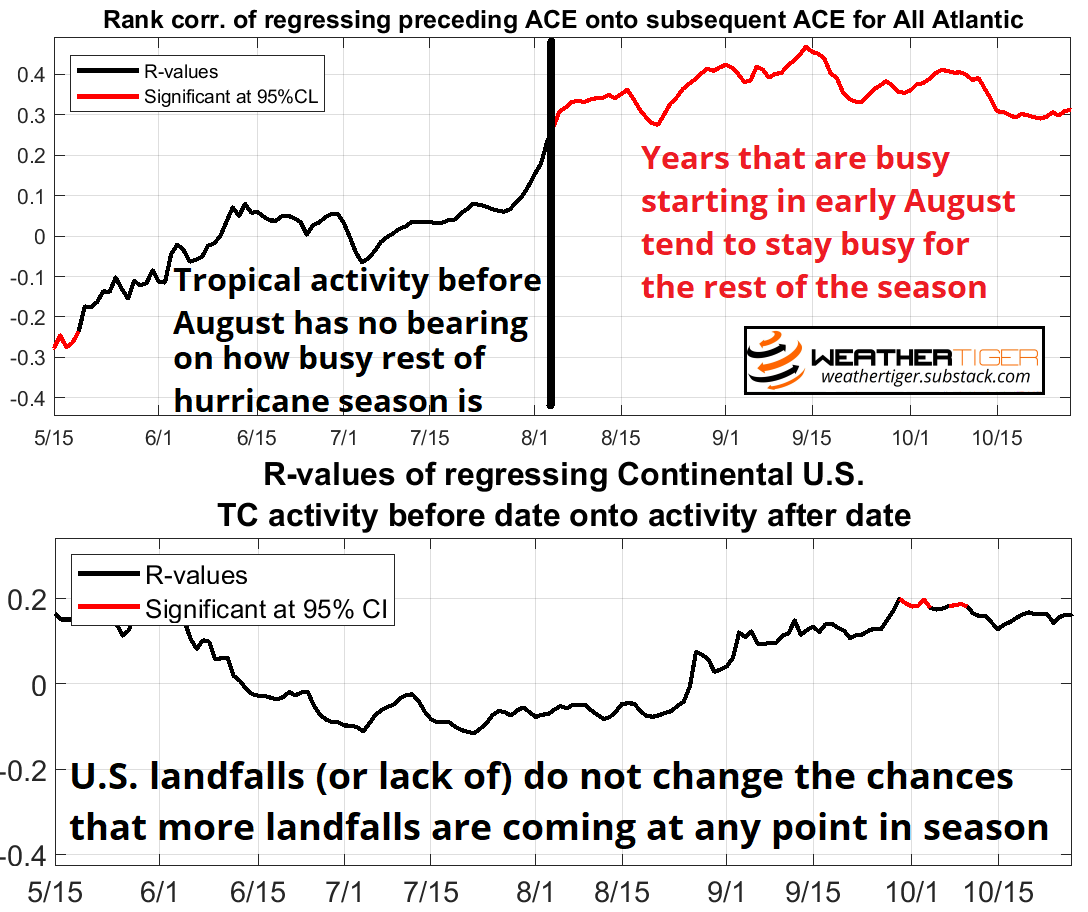

However, past performance does not predict future results: there is no relationship between U.S. landfall activity prior to August and how many landfalls occur in the rest of the season. An early season hurricane doesn’t mean more are coming in the peak months, and vice versa. For overall activity, a busy August in the Atlantic corresponds to only a marginal increase in the odds of an active September and October, while June and July, like Jim Cramer, have no predictive power.

The Forecast

Will our early luck hold out? If you’ve read WeatherTiger’s previous seasonal outlooks or follow our real-time probabilities, you know it’s hard out here for a seasonal hurricane forecaster. The two most reliable predictors of tropical activity, Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and El Niño/La Niña, suggest divergent outcomes for the 2023 hurricane season. That chasm has expanded further this summer, and is now the size of the gap between the palettes of Barbie and Oppenheimer.

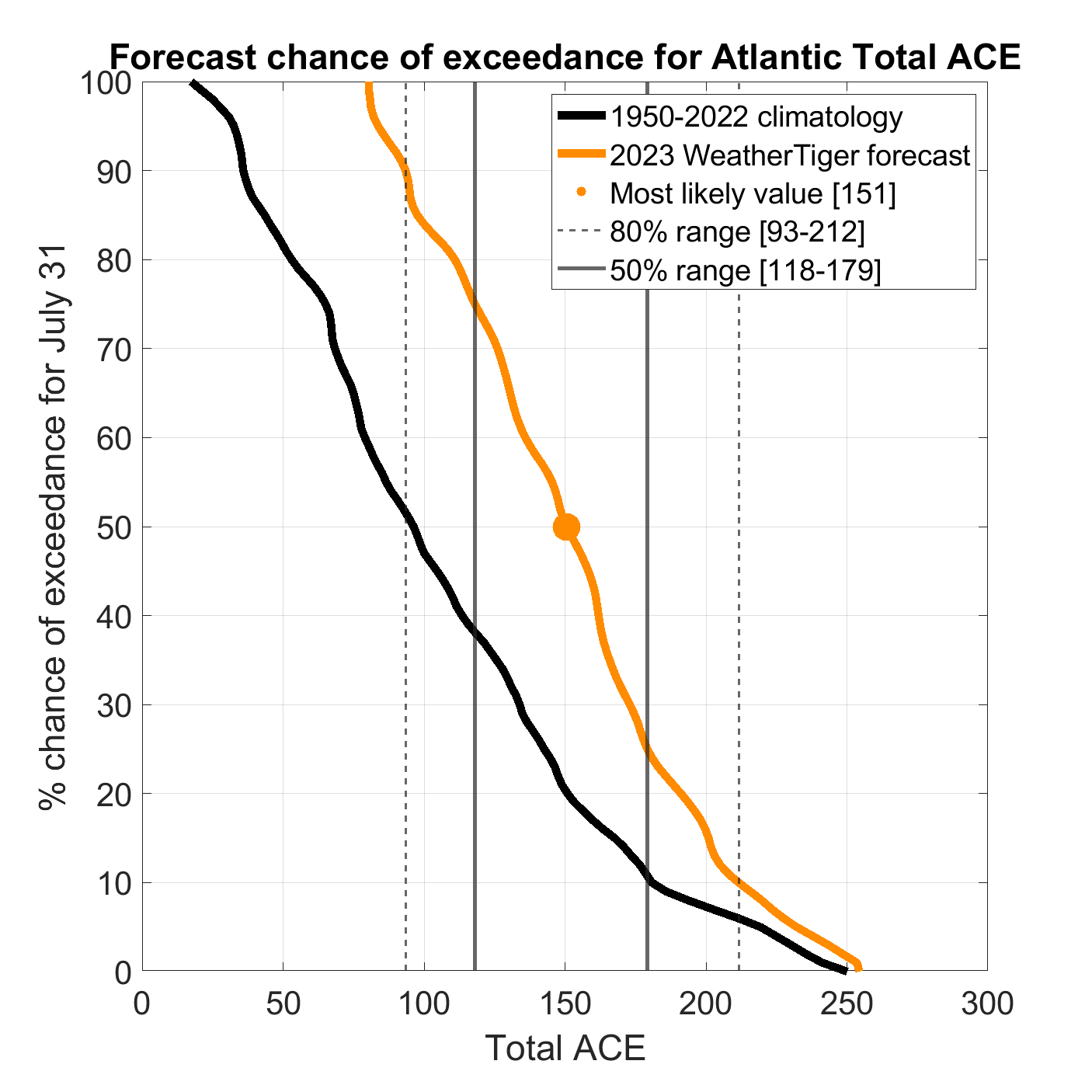

WeatherTiger’s real-time seasonal forecasting algorithm has been making sense of this as best it can, though only a fool would be confident in what comes next. As of early August, our model now projects a most likely outcome of around 150 units of Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), which is about 50% above the average season’s 100 ACE units.

That corresponds to a 30-35% chance each of a hyperactive (>165 ACE), above average (125-165 ACE), or near normal year (73-127 ACE), and a less than 5% chance of a below normal (<73 ACE) season. These odds may continue to shift as the peak approaches, and you can monitor WeatherTiger’s daily ACE model runs in real-time here.

This is a significant adjustment in the direction of more activity over the last two months. Our model has packed 50 ACE units onto its forecast since late May, including 15 ACE units that have already occurred, boosting the odds of an above average season from 25% to 35% and the chance of a hyperactive season from just 5% to 35%. We’re not alone. Predictions from Colorado State, the European Center, and others have all been revised higher, and NOAA and additional groups may follow suit in the next week.

Going El Niño

You might think that the cause of that change is another predicted El Niño event failing to launch, but that’s not the case. El Niño got rolling as projected early in the summer and has since intensified to a “moderate” event, with SSTs averaging more than 1°C above normal in the Equatorial Central Pacific and models projecting more strengthening to come.

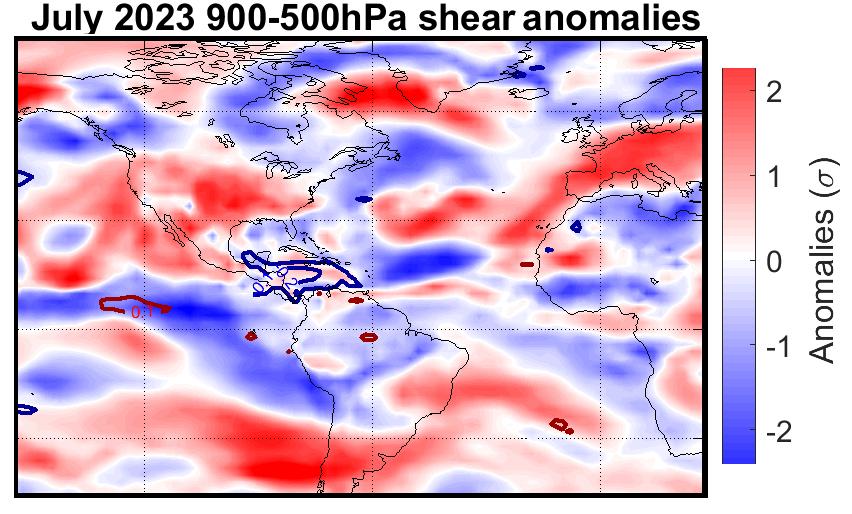

El Niños create storm-shredding upper-level wind shear over the Caribbean and Gulf and mean fewer Atlantic hurricanes. While Niño 23’s grip on the world’s weather is not ironclad yet, wind shear in the Caribbean was, as expected, stronger than average in July (above). These shearing winds tend to persist once established, which is one continued argument for a milder season.

Atlantic Heat

The issue is Atlantic SST anomalies have gone from ridiculous to sublime in the past two months. Summer SSTs between Central America and West Africa and north towards western Europe are a top predictor of seasonal activity, as loosely defined by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) index. The AMO hit all-time record warmth in June, and the June-July average is almost certainly above the recent benchmarks set in 2005, 2010, 2017, and 2020. Those four years averaged almost double the Atlantic tropical activity of a normal season.

Yet bringing the Pacific back into the fold, none of those years are strong analogs. Each of those four seasons had either a mature or developing La Niña, which acted to also keep the upper-level winds in the Atlantic more favorable for hurricane activity than normal. The takeaway, as shown by the colorful dots below, is when the Atlantic is this hot, hurricane seasons are above normal (orange) or hyperactive (red). When the Pacific is this hot, hurricane seasons are near (gray) or below normal (blue). Earlier, WeatherTiger’s model was calling for a draw, but is now projecting that the Tropical Atlantic has become so warm that the thermodynamic runaway train will win out over unfavorable upper-level winds, and it will be a busy season.

And maybe that is true. It wouldn’t surprise me, and we should be prepared for it as individuals and as a society. But the internal model signals are deeply mixed, and as a seasonal hurricane forecaster, I’m skeptical of the utility of seasonal hurricane forecasts this year. None of the techniques were designed to work this far outside the normal range of variability of key inputs, so the potential for large forecast errors is higher than usual.

My Final Thoughts

Because of all this, if I had to pick, I’d take the under on WeatherTiger’s own model. Hurricanes form when all the necessary meteorological conditions for development are in place, not just some of them, and very busy seasons happen when those raw ingredients are consistently present in August, September, and October. Given the robust El Niño, predicting a hyperactive hurricane season in 2023 feels a little like saying you can bake a cake without flour by turning the oven up to 700°.

Overall, taking summer El Niño and AMO conditions together, 2023 is simply off in its own universe, where the Atlantic is hot, the Pacific is hot, UFOs clog the skies and no one cares, and superconductors work in a sauna but only on the Internet. It’s a lot, and recent experiences have not built trust we’re heading anywhere good. Objectively, odds of an active season have risen, but there’s a lot going on beneath the surface. Next week, I’ll discuss WeatherTiger’s U.S. landfall modeling, and where hurricanes might predominantly form and track this year in part two of our outlook (subscribers check below for a sneak peek). In the meantime, kids, remember to impress your teacher by putting your summer reading book report in a professional clear plastic binder, and keep watching the skies.

Part II: Landfall Risks

Originally published August 10, 2023.

The French painter and philosopher Paul Gauguin once asked, “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” As a humble scientist, I leave the middle question for humanities majors to ponder, but will point out that where hurricanes are likely to develop and then move is an under-discussed aspect of seasonal prediction. As Gauguin’s South Pacific home base of Tahiti is almost never impacted by tropical cyclones, maybe the guy was on to something.

Where hurricanes come from and go is important, as seasons with similar overall activity can have divergent human impacts. In 2004, nine Atlantic hurricanes caused six U.S. hurricane landfalls and $60 billion in damage. In 2010, twelve Atlantic hurricanes caused zero direct hits and pocket change losses.

Busier seasons, on average, do yield more U.S. landfall activity, but the relationship is weaker than you’d think. Even if you knew with metaphysical certitude how much Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) was going to occur in the Atlantic before the season started, you could only predict about one-third of the year-to-year differences in how much ACE happens over the continental United States. The rest of the variability stems from where storms develop, where they move, and, to be honest, a lot of dumb luck.

Last week, I discussed why WeatherTiger’s August hurricane season outlook has shifted more active since spring, with an uncertain forecast for net Atlantic activity about 50% higher than average. The primary culprit for this is across-the-board, Quiznos-level toastiness in Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs), with a pepper bar of especially picante oceanic warmth in the Gulf of Mexico. We’re not alone in noting this trend, with the consensus of seasonal forecasters rising from roughly 130 to 160 ACE between early June and today.

This week, I’ll dig into the thornier question of when and where that activity may pop up. Like grappling with Gauguin’s ontological quandaries or locating a Quiznos in 2023, that’s a tough task. But we do these things not because they are easy, but because they are toasty.

Where do they come from?

If seasonal hurricane forecasting is already a hard problem, predicting U.S. landfall risks is tougher than leather. A first step in that direction is to understand how U.S. impact risks vary with storm location; as shown below, a random storm in the eastern Tropical Atlantic has about a 10% chance of reaching the U.S. as a hurricane, while one in the Gulf or Caribbean has a 30-40% chance of eventual U.S. hurricane landfall. Storms in central or eastern subtropical Atlantic are of no concern.

That historical analysis has the logical conclusion that a tropical system developing closer to the U.S. coastline has a better chance of making landfall. There simply is a much wider range of tracks that will cause a problem for a storm in the Gulf versus one near west Africa. However, storms usually develop in the eastern Atlantic only in August and September; early in the season and again in October, the environment in the Cape Verde region is unfavorable, and tropical development clusters in the higher risk regions closer to the U.S. coast. For this reason, June, July, and October account for around one-quarter of total ACE, but punch well above weight at over 40% of historical U.S. ACE.

This year, however, the shoulder season is a little less of a worry. Grimace’s Birthday and Shark Week have passed without incident, and a strengthening El Niño reduces odds of late season landfalls.

Per WeatherTiger’s analytics, the years that are the best historical matches to current El Niño conditions (and other key global dimensions of compatibility) are 1939, 1951, 1965, 1972, and 1997. In these five seasons, lower-level winds between August and October blew more strongly than normal out of the east, and more strongly out of the west at upper levels. This sharp change in the direction and strength of winds with height meant more wind shear (unfavorable for hurricane development) over the Caribbean, southern Gulf, and Lesser Antilles. As such, little tropical activity was noted there, and no U.S. hurricane landfalls occurred in October in any of those years. Interestingly, shear is already above normal in the Caribbean in 2023, and expected to stay that way into late August.

On the other hand, average upper- and lower-level winds in 1939, 1951, 1965, 1972, and 1997 were normal in the eastern Tropical Atlantic and southwestern subtropical Atlantic. With extreme ocean warmth in these areas and no historical signal for more inclement upper-level winds, areas east of 50°W or north of 20°N may be the preferred zones for storm formation this season. While these development regions are historically less risky for U.S. landfalls, the risk is, of course, not zero.

Where are they going?

The historical probability of U.S. hurricane landfall is not only dependent on where storms form, but the pattern of steering winds that move them about once they develop. With August and September accounting for two-thirds of Florida’s major hurricane landfalls and October likely hobbled to some extent by El Niño’s wind shear, it is the potential steering regime over the next six to eight weeks that is of the greatest interest in 2023.

All of Florida’s 20 major hurricane landfalls in August and September since 1900 approached from the south or east and initially struck the Keys or southern half of the peninsula. Three days prior to these landfalls, there were strong, amplified high-pressure systems aloft over the western Atlantic and Eastern Seaboard. The clockwise windflow around these blocking ridges steered the storms west or northwest and prevented a turn into the open Atlantic. Furthermore, strong troughing over the U.S. Plains and central North Atlantic were also present to keep the ridge itself from sliding out of position.

The top analog years to 2023 do not show a close match to that inauspicious steering pattern. In August of 1939, 1951, 1965, 1972, and 1997, protective troughing was generally located over the U.S. East Coast, a pattern that so far has been repeated in 2023. However, in September, the analog steering pattern is more mixed, with indications of intermittent Southeastern or mid-South ridging. This signal is weaker and further southwest than the nightmare highs preceding catastrophic Florida landfalls, but it does hint that the door could be open for potential hurricane threats to the U.S. coast at intervals.

However, since development may focus on the eastern half of the Atlantic, many storms would also have to negotiate a potential trough in the central Atlantic plus wind shear obstacles before threatening the U.S. coast, which history shows is a tall order. Some analog and long-range modeling projects occasional high-latitude blocking in September, but overall the indications for the steering regime in the peak season are not particularly alarming.

What are we?

So, we’re looking at a 2023 hurricane season with more overall activity than normal, predominantly developing at an atypical remove from the U.S. Steering wind risks are a push, and the final quarter of the season will likely be calmer than average. Unlike most other seasonal outlooks, WeatherTiger has developed a predictive algorithm that integrates the various components of landfall frequency into a specific projection of how many units of ACE will occur over the continental U.S. A normal year would have about 4 more units of U.S. ACE after mid-August.

However, our U.S. landfall risk model is coming in below this, at around 2.5 to 3 U.S. ACE units. This is interesting, not only because it diverges from our above-average overall activity forecast, but because WeatherTiger’s U.S. landfall projection declined in July and early August. Much of this decline simply reflects that about a quarter of U.S. landfall risks are now behind us, but it may also indicate that steering winds and preferred development locations aren’t particularly conducive to threats in 2023. Even so, our forecast translates to a 70% chance of at least one and a 40% chance of two or more U.S. hurricane landfalls this season. As a final note, our landfall model projected above normal landfall risks in 2022, which unfortunately was accurate. Here’s hoping for above-average forecast accuracy for below-normal landfalls in 2023.

In closing, the Tropics remain quiet, and are likely to stay that way for another week. Still, we know well that hurricane seasons can be nowhere to be found, then suddenly everywhere, like pickleball in 2023 or Quiznos in 2003. While there is hope that the potentially active peak months ahead may not translate into destruction, it only takes one to moot that whole thesis, so keep watching the skies.