Next Top Model '24: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for August 22nd

Counting down WeatherTiger's 2024 computer model power rankings as the Atlantic remains quiet for now.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get daily tropical briefings, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions.

The statistician George Box once said, “All models are wrong, but some models are useful.” Given Box’s research interests, this quote refers to developing robust industrial quality metrics in the 1960s. It is, however, even more applicable to weather models in 2024, an imperfect but essential part of the hurricane forecast process.

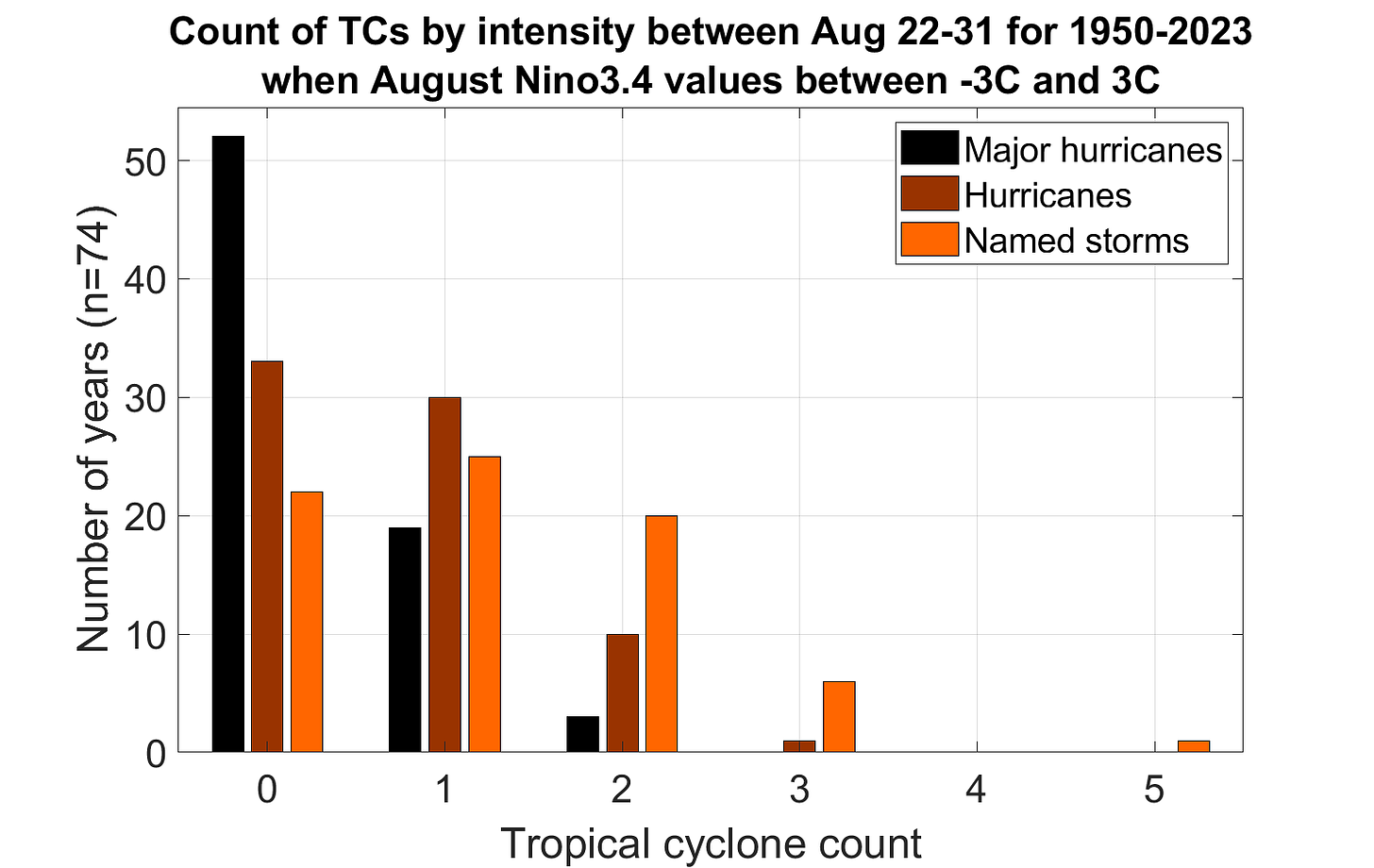

So, let’s talk about the models. In the short term, all numerical guidance is blessedly quiet, indicating no significant tropical threats to the continental United States for the rest of the month. That the Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean are devoid of hurricanes in late August is even more surprising than no one having yet made a Killers/Charli XCX mashup called “Mr. Bratside.1” Usually, one to two named storms form in the Atlantic over the next 10 days, so the fact that I’m only drinking one to two LaCroix per day here at WeatherTiger World HQ is a real shock to the system. But we’ll take it.

The reasons for this delayed peak aren’t the Atlantic’s usual excuses. Weak upper-level winds, a strong African monsoon, and near-record sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region, in isolation, all argue for plenty of storm activity in late August. However, these favorable factors are collectively working against each other for now.

Tropical waves are usually held back by wind shear arising from low-level winds blowing from east-to-west and upper-level winds blowing from west-to-east; this week, the dominant wind direction in each of those layers is reversed. That’s a bizarre but unfavorable configuration, one not likely to last into September. Still, it’s going to be another week or more before tropical waves have a real shot at developing in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region. One feature that to keep half an eye on over the next seven days is some scattered convection north of Hispaniola, which may make its way into the Gulf. However, this disturbance is starting from scratch at the low levels, so any development is unlikely. Look for enhanced rain chances along the Gulf Coast from the weekend into the middle of next week.

Meteorologists can make predictions like that with relative confidence thanks to computers’ incredible facility with repetitive math problems. Models use information about current weather conditions and the physics equations that describe how fluids move to estimate how the atmosphere will change with time. These models are capable of simulating hurricanes, but their approximations of the complex physics in the core of a storm are rough.

Some forecast models are run as ensembles, in which many versions of the same model are made by tweaking initial weather conditions — for example, shifting the starting location of a hurricane by a few miles. These small differences can have big long-term impacts, so the way the ensemble members spread out with time gives a sense of forecast uncertainty. Averaging the opinions of many ensemble members (or many different models) also results in a more accurate prediction.

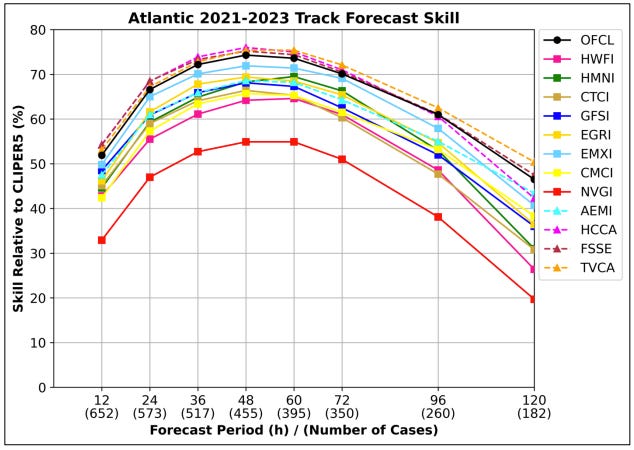

Confusingly, there are a wide assortment of models available to the public and huge differences in forecast skill between them. Building on validation data from the 2023 season NHC Forecast Verification Report, here’s a rundown of hurricane models in approximate order of least to most useful. (WeatherTiger’s 2024 rankings are unofficial and unaffiliated with the J.D. Power & Associates Award for Best Mid-size Luxury Sedan Powertrain Warranty.)

NAVGEM, NAM, and miscellaneous. The NAVGEM, NAM, and various model barrel-scrapings are useful, in that if someone posts their hurricane output, you can be certain they trying to scare you for the clicks or alternatively just have no idea what they are talking about.

ICON. The German ICON is a newer model that occasionally catches on to a trend early, as it did during Ian. For every success, there are several wild misses, which coupled with a limited ability to resolve strong storms makes it unreliable.

Canadian (CMC). The Canadian model is respectable prognosticator of mid-latitude jet stream patterns, which can be useful. However, it doesn’t handle convection—and thus hurricanes—particularly well, limiting its forecast value. Did well at long ranges in 2023.

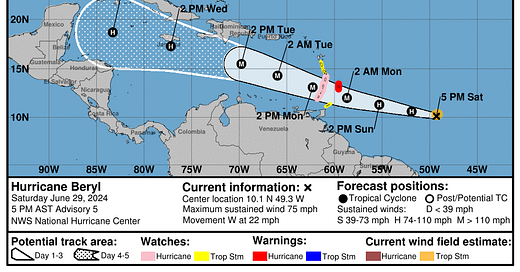

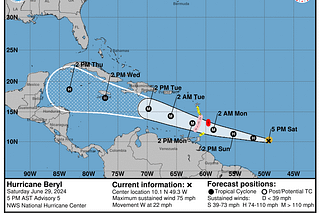

COAMPS-TC. A hurricane-specific model run by the U.S. Navy, COAMPS-TC had a rough 2023 season but caught on early to track and intensity trends with Beryl this year. Drawbacks include limited availability of output and a sometimes-inconsistent schedule of model runs.

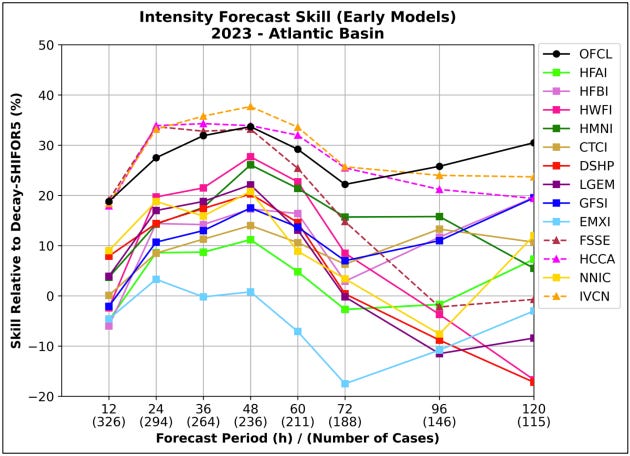

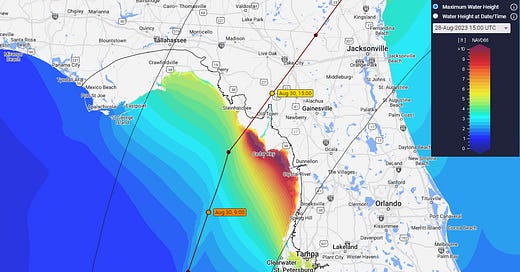

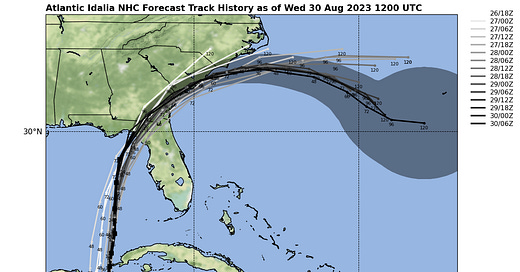

HMON and HWRF. The HMON and HWRF are the older generation of American hurricane models, designed to simulate the complex inner cores of hurricanes. These models are known for a perpetual bias in favor over-strengthening storms in marginal environments; they have also whiffed too far west on Ian, Idalia, and Debby in recent years. HWRF and HMON did worse in 2023 than the newer hurricane models, and are slated for retirement in 2025. Given their bullish biases, look for these models to go to their viking funerals swinging.

British (UKMET). The UKMET ranks second-best in overall global weather pattern forecast errors. For tropical weather, it is an independent opinion worth considering; for instance, it took Ian into Southwest Florida. The UKMET’s short forecast period, delayed ensembles, and limited availability make it a little less useful to forecasters.

American (GFS). The main American global forecast model, the GFS underwent an upgrade several years ago that improved its reliability for hurricane forecasts. The GFS and GFS Ensembles have struggled in the last few years, in particular taking Ian, Idalia, Beryl, and Debby too far west, but over the long-term it isn’t too far behind the Euro in track forecast accuracy. It also outperforms all other non-hurricane-specific models in intensity forecasting.

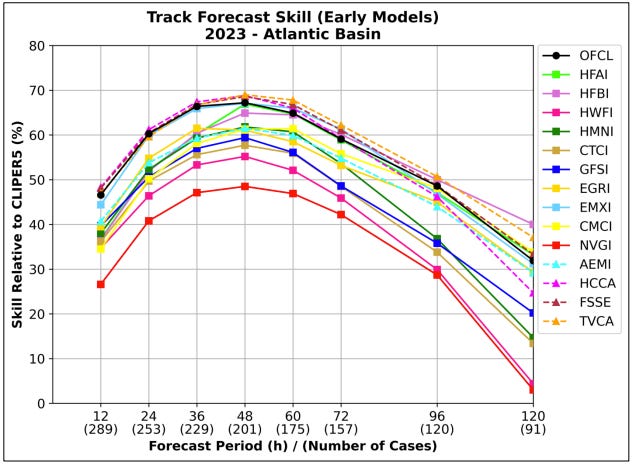

HAFS-A and HAFS-B. The HAFS bros are the next-generation American hurricane models, which moved from experimental to operational status in 2023. HAFS is a major step forward, combining the strengths of global and hurricane-specific modeling, and HAFS-B was the top performer in 2023 at the three- to five-day forecast range. Upgrades to HAFS are continuing, so look for more skill improvements to come. This is the way.

European (ECMWF). The predictive power of the European model for global weather patterns remains unequalled. For hurricanes, “King” Euro has the best average track skill over 2021-2023; it also did relatively well with Ian, Idalia, and Debby, keeping their tracks consistently and correctly east of the American models. Still, kings are human, and the Euro has feet of clay in intensity forecasting.

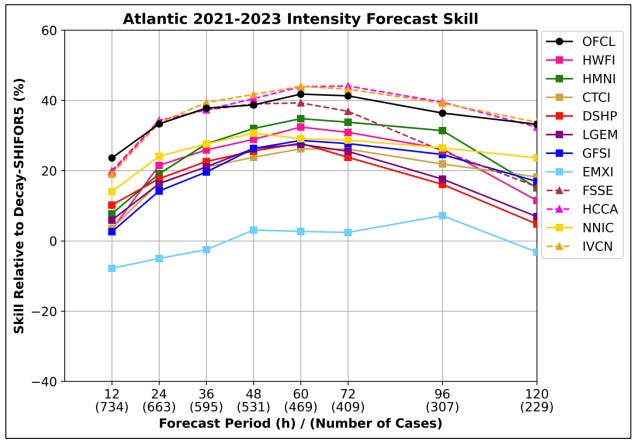

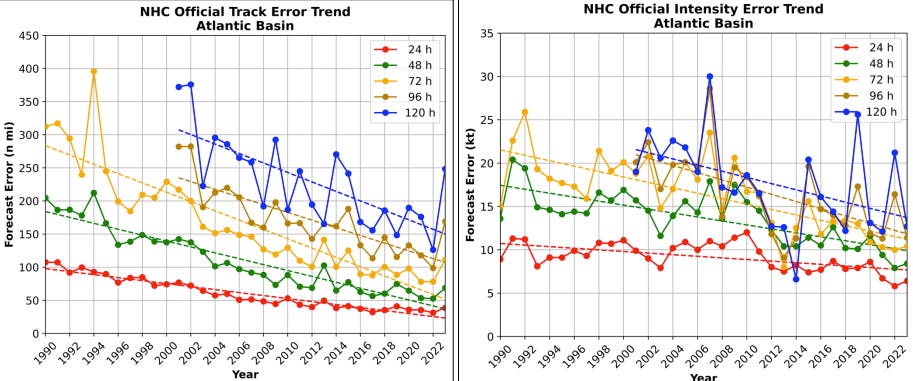

NHC official forecast. Over the past several decades, the National Hurricane Center’s one- to three-day track forecast errors have diminished by 75%, with reductions of about 60% at four- and five-day lead times. Intensity forecasts have also improved, though less dramatically. In the past three years, official National Hurricane Center track and intensity forecasts bested all individual models and equaled the best model blends at all lead times. NHC average forecast errors for the 2023 season were higher than in recent years, mostly due to wackadoo Tropical Storm Philippe’s refusal to curl out to sea in October, so the 2024 cone is a little larger this year than last.

Still, NHC forecasts are far more consistent than any individual model, which typically jump around 75 miles or so each six hours at a four-day lead time. NHC four-day forecasts are not only more skillful than individual models, but shift less than 50 miles on average between advisories. That makes them more accurate than models, and more dependable.

Are models actually useful? The answer is a clear yes for the experts and professionals who are equipped to interpret and assess their output. They probably are not very helpful for the public, particularly as the scariest models find the most eyeballs, irrespective of quality. The good news is, unless you are a professional forecaster, you really don’t need to look at models. While an individual model may outperform the NHC for any given storm, over time the NHC’s meticulous approach wins. Use as directed, and keep watching the skies.

Somebody make this!!

Great information!

“60% of the time, these models work every time.”