All Your ACE Are Belong To Dust: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for August 24th

Discussing the causes and effects of a bizarrely calm August in the Atlantic.

If you are not already a supporter, please consider signing up for a paid subscription to WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch. You’ll get Florida-focused tropical briefings each weekday, plus weekly columns, coverage of every U.S. hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions, for $7.99/mo. or $49.99/yr.

Ah, late August. A time when the great voice of the people rises in one accord, delivering a clear, unified message to our leaders: Stop2End.

While “opting out” of the political logorrhea spilling out of our phones is as effective as repeatedly jabbing an elevator’s door close button, perhaps our digital entreaties for something, anything to end are not so futile after all. Nearly three months in, Hurricane Season 2022 has had the uncommon decency to not just stop, but never get going in the first place.

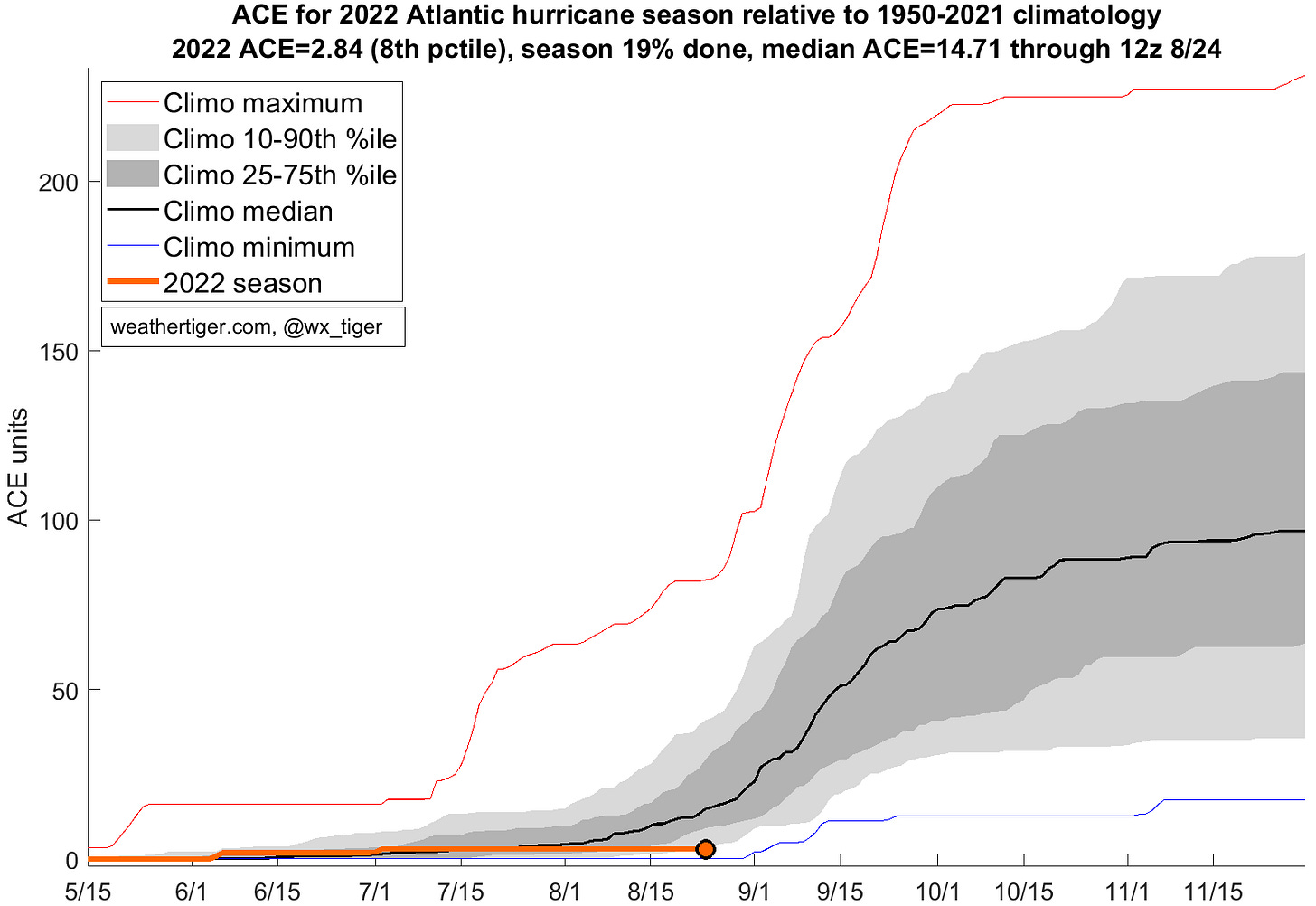

On the 30th anniversary of Hurricane Andrew’s landfall as one of just four Category Five landfalls in the continental U.S., the hard numbers tell a different tale this year. It has been 52 days since the last named storm in the Atlantic, Gulf, or Caribbean. Just six hurricane seasons since 1950 have tallied less Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) than the paltry 2.8 units generated this year through August 25th. That makes 2022 the slowest start to a hurricane season since 1988, so long ago that Nick-at-Nite was airing timeless, quality programming rather than Young Sheldon.

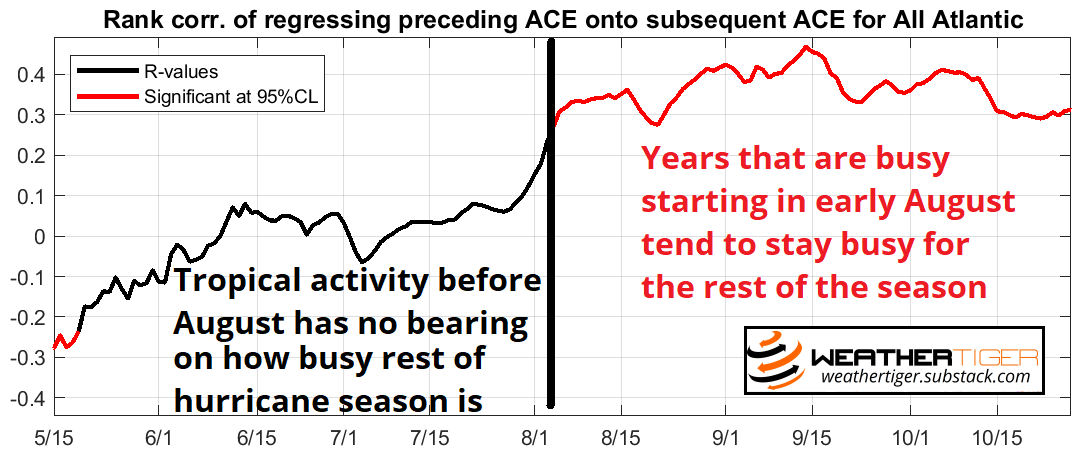

A pacific Atlantic in August has implications for the remainder of hurricane season. While tropical activity in June and July has no correlation with ACE for the rest of the year, there is a small but significant tendency for slow Augusts to be followed by less activity in September and October. This is because an unfavorable tropical environment in late summer can linger into the early fall peak of hurricane season.

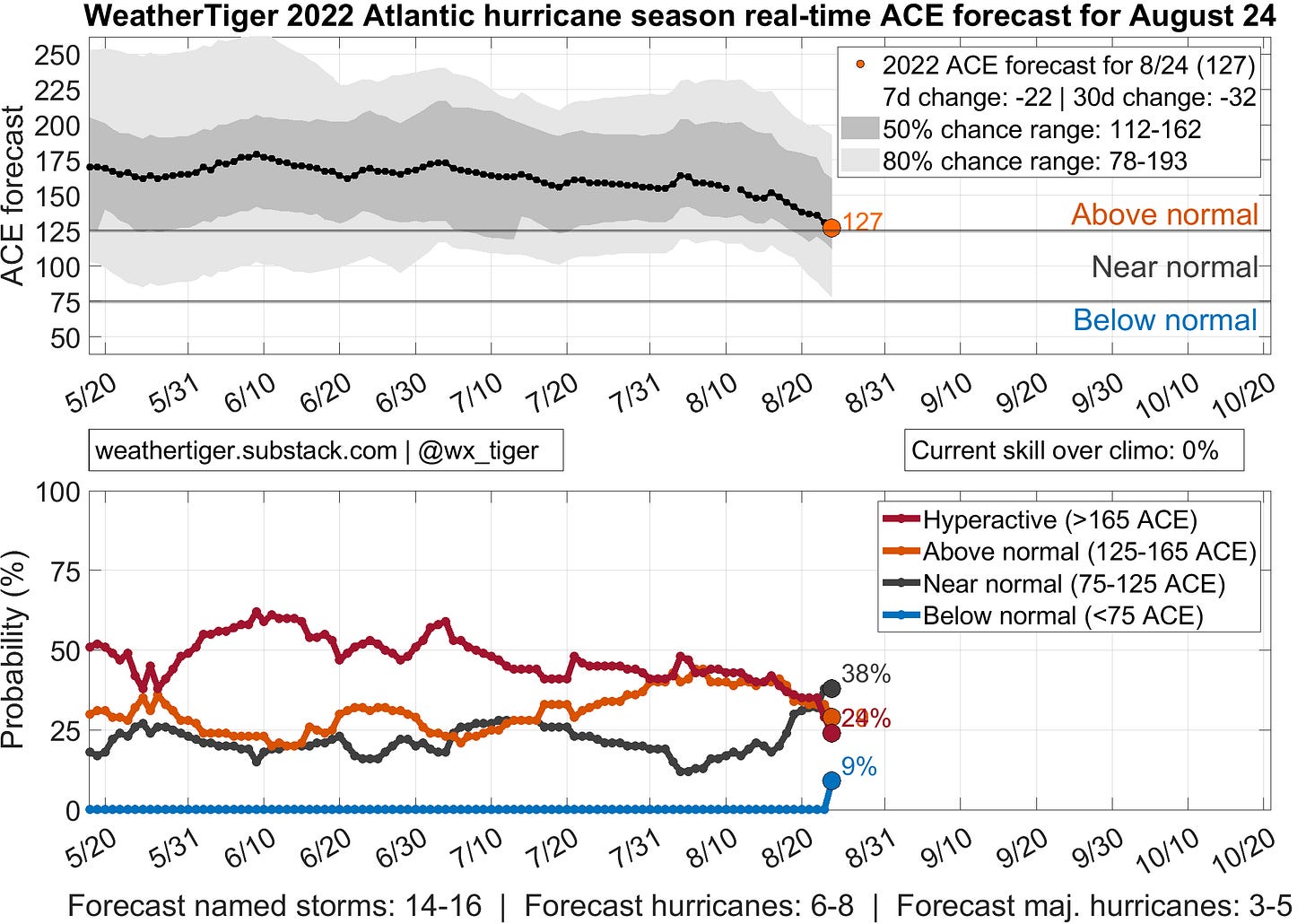

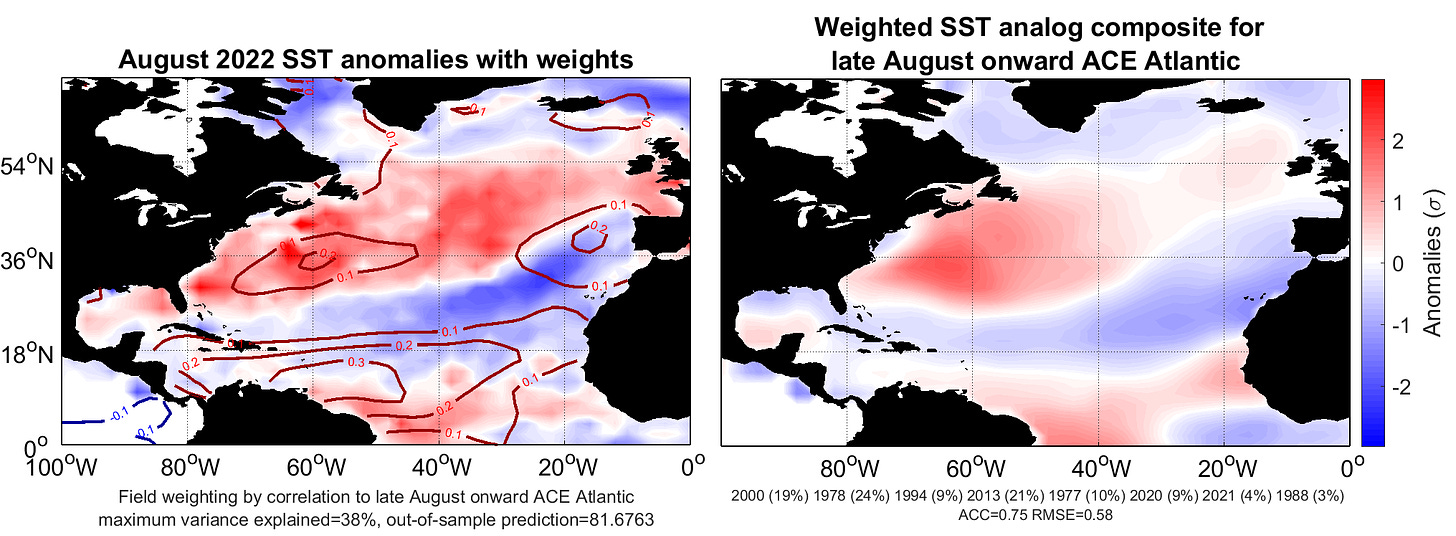

WeatherTiger’s most recent seasonal outlook, along with NOAA’s and pretty much every other forecast group, called for above normal chances of an active season, citing a strengthening La Nina and warmer than average waters in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region (MDR). These factors typically presage favorable conditions for hurricanes to form in the peak of the season.

Keyword: typically. While those factors remain in place, there have been dramatic changes in three key parameters that are more difficult to predict ahead of time and account for August’s inactivity.

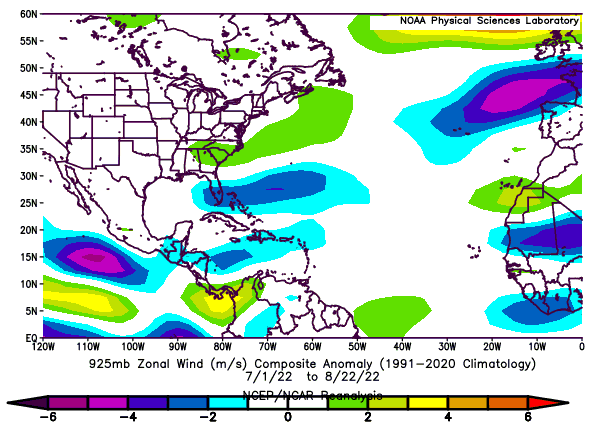

First, the Eastern Pacific Ocean has had frequent hurricanes in July and August, which is unusual during a moderate La Nina. All that rising air from Eastern Pacific storms must come down somewhere, often over the Gulf and Caribbean. This influx of descending, stable air is why busy Eastern Pacific seasons tend to be quieter in the Atlantic. La Nina appears to be finally winning the war in the Pacific, and no hurricanes are expected west of Mexico for the next week or more. That, combined with a supportive pulse of the Madden-Julian Oscillation, might improve the environment in the western half of the Atlantic Basin heading into September.

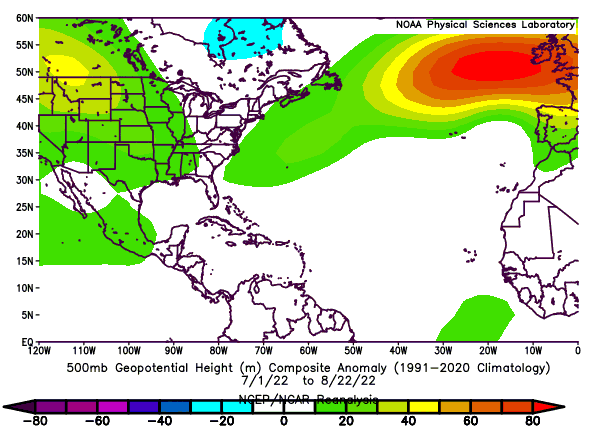

The eastern half of the Atlantic remains a mess. While the MDR remains a little warmer than average, the second issue is sea surface temperatures north of the Tropics have changed dramatically in the last few weeks. The subtropical (20-35°N) ocean has cooled, while the mid-latitude (35-50°N) Atlantic is now experiencing record warmth. Maine lobsters aren’t quite being caught pre-boiled, but it’s close.

Adding this up, the north-south gradient in Atlantic temperatures is much less than normal this year, causing a northward shift in the jet stream. This meant a sweltering summer in Europe, and made it easy for dry, stable airmasses from the mild subtropics to drift into the MDR, where mid-level humidity has been far below normal this August, squelching otherwise healthy tropical waves. This pattern doesn’t look to alleviate in the next few weeks, so eastern Atlantic disturbances will probably keep struggling in September.

The third contributor is the infamous African dust machine. Stronger than normal easterly trade winds over the Sahara have swept copious desert particulates over the Tropical Atlantic this summer. These dust grains warm the mid-atmosphere, increasing the stability of an already dry airmass and preventing convection. Tropical storms organize from these convective building blocks, so from a scientific perspective it is appropriate and necessary to state that in A.D. 2022, all your ACE are belong to dust.

So where does that leave us? Well, with about 80% of both historical Atlantic ACE and Florida hurricane landfalls still to go. The put-up-or-shut-up zone of the most active 45 days of the season starts now and historically contains about two-thirds of total activity. With convection crippled by the dust that keeps on blowing and dry air cutting waves open, WeatherTiger’s real-time seasonal model keeps bleeding, keeps, keeps bleeding ACE each day the Atlantic stays quiet. Nevertheless, the most likely projected outcome is now a near-normal season, with around a 40% chance of 75-125 ACE.

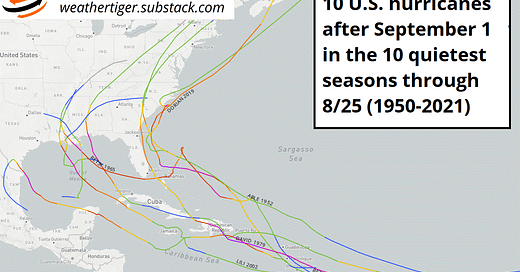

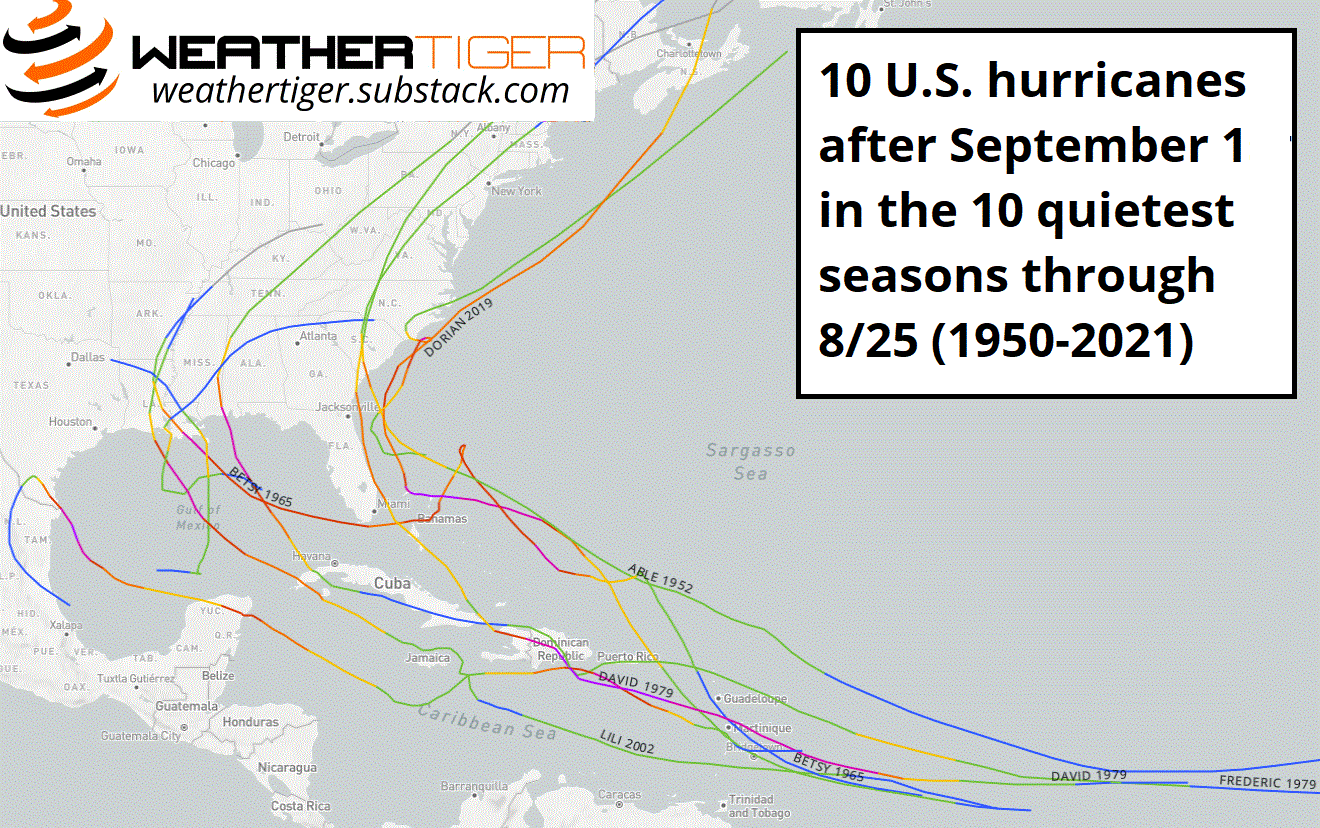

In fact, most of the seasons that started comparably slow to 2022 and then stayed inactive were El Nino years. The ENSO-neutral 2019 season produced a similarly pathetic 4 ACE units through August 25th, and then 128 including Dorian after that. The 1988 season kicked into gear in September and October, producing Category 5 Gilbert and 102 ACE under a La Nina influence. In the 10 seasons since 1950 with the quietest starts through August 25, an average of 1 U.S. hurricane landfall occurred on or after September 1st.

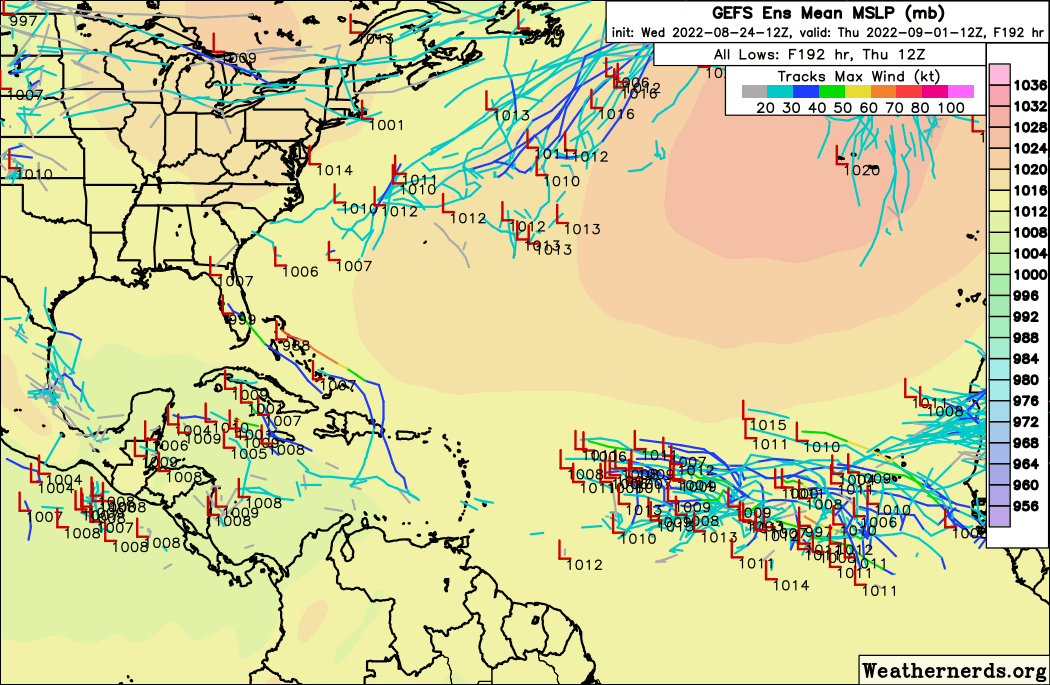

There is no real way of knowing whether the recent calm will continue. Currently, the NHC is tracking two tropical waves between West Africa and the Lesser Antilles. These waves are contending with the same dry airmasses to their northwest that have been an issue throughout August, so development prospects in the short-term remain modest. Models have been repeatedly overestimating development odds 6-10 days out, so a prove-it posture is reasonable. However, it makes sense to keep an eye on the further west wave as it moves through the Caribbean next week. With the Pacific quiet, the Gulf and Caribbean may be a more conducive environment for development than the eastern Atlantic, and steering currents would not preclude a possible U.S. threat if something were to organize.

So, while stop2end remains the text of angry men, the SMS of a people who will not be spammed again, at some point the belated 2022 hurricane season will inevitably start to begin. The example of Andrew shows it really, truly only takes one to make a season miserable, so keep watching the skies.