Summer, Low Landfalls: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for July 17th

A quiet Atlantic offers a chance to contemplate July hurricane history, a month in which U.S. hurricane impacts are uncommon.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

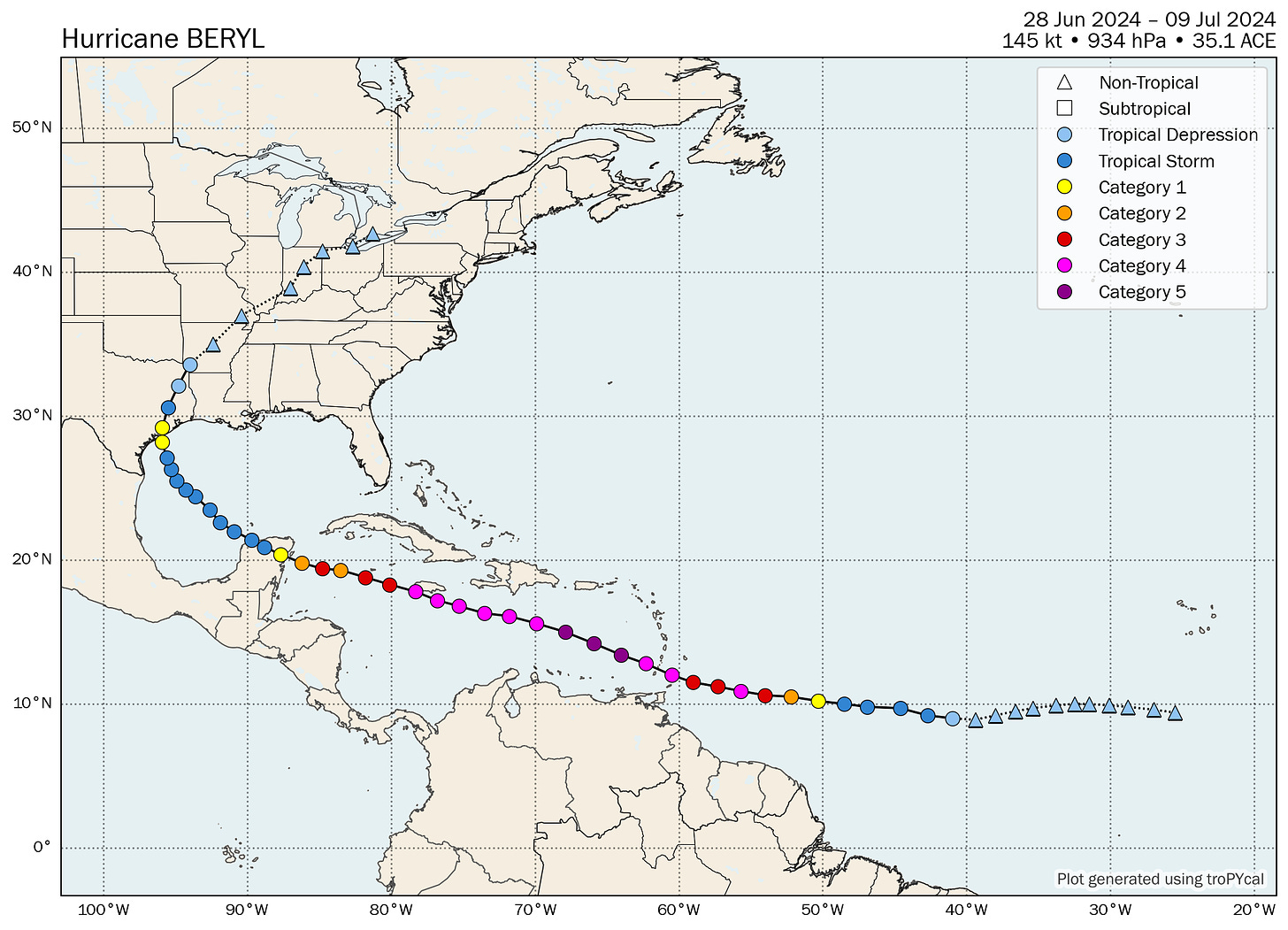

The hurricane climatology adage “June, too soon; July, stand by; August, come they must; September, remember; October, all over” can be traced back to the British Caribbean fleet of the 1800s. While this mnemonic device freed up bandwidth for vigilance against krakens and the zany antics of Johnny Depp, “stand by” is notoriously ambiguous phrasing. In most years, “stand by” might overstate July’s case for tropical activity; in 2024, those ancient mariners’ words were far too passive for the Category 4 landfall on the Windward Islands, Category 2 landfall on the Yucatan peninsula, and Category 1 landfall in Texas from devastating Hurricane Beryl.

Of course, sure as sunshine after the rain, power hasn’t even been fully restored before the murmurings of “where are the hurricanes you predicted?!” begin. The answer is: in July, usually in an ocean other than the Atlantic. To wit, when Apollo 11 was returning from the moon 55 years ago this week, its splashdown location in the Western Pacific had to be shifted 250 miles at the last minute due to a developing tropical disturbance. Meanwhile, the Atlantic hadn’t even seen a named storm to date in 1969.

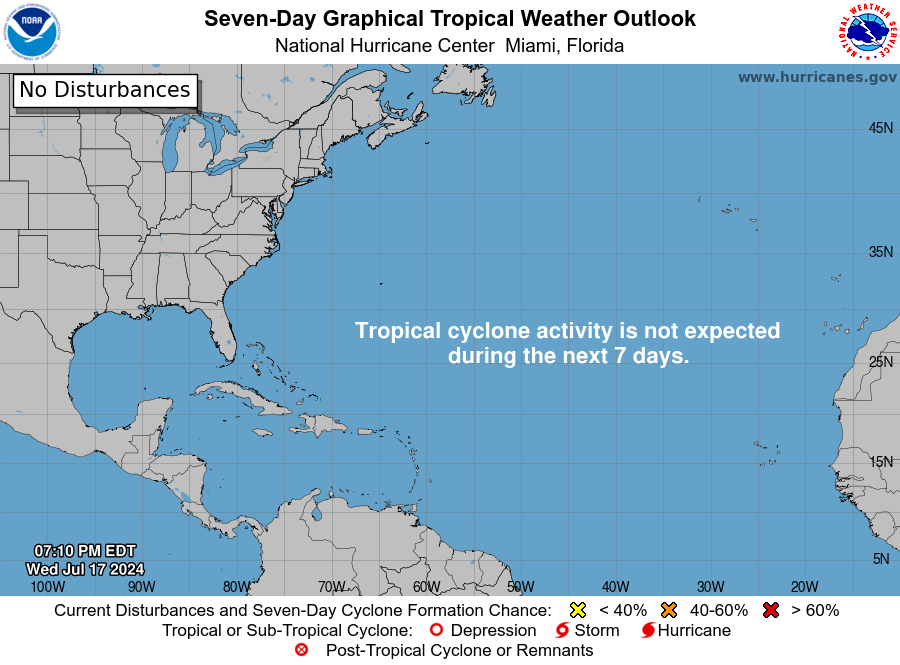

While Beryl was a July hurricane for the ages, the rest of July 2024 looks to uphold the Tropical Atlantic’s languid tradition, as there are no tropical disturbances in the Atlantic, Caribbean, or Gulf with a realistic chance of development over the next week. Some tropical moisture may start to enhance rain chances in Florida starting Monday, but it won’t be anything organized. Saharan dust, high wind shear, and sinking air aloft should remain in place over the Tropics through the end of the month, making any development an uphill battle for the foreseeable future.

In this second entry in our six-part guided tour of hurricane season, we’ll see that July is a month that entails quite a bit of boredom, as well as slap a letter grade and a rewrite on that climatological assessment of the Masters and Commanders of yore. (You can read part 1, June, here.)

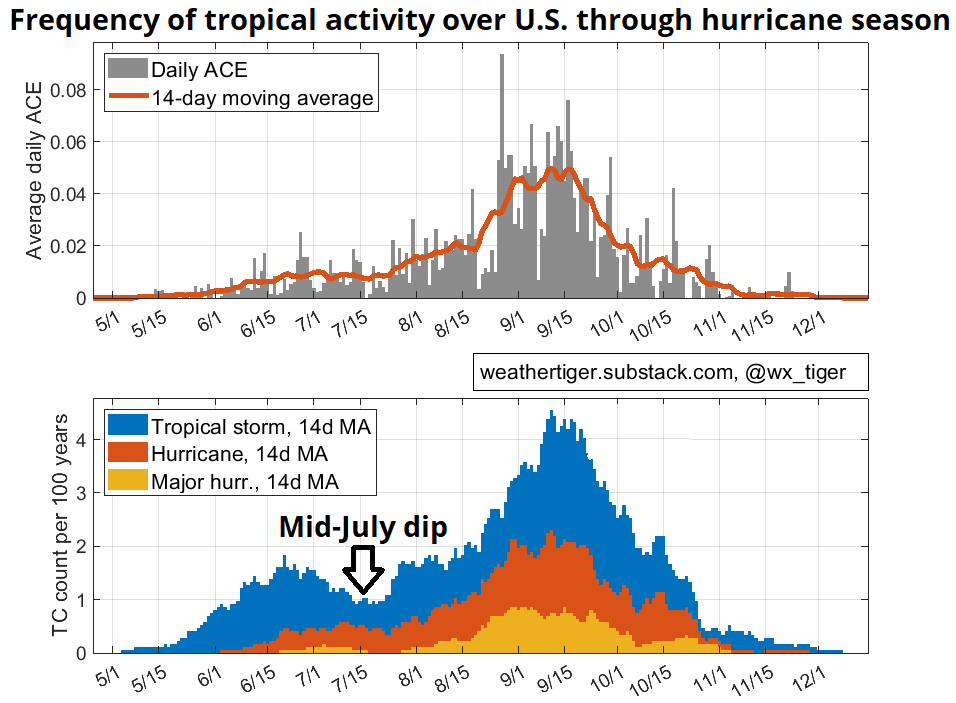

By the numbers: July and September are both months in hurricane season the same way that Earth and Jupiter are both planets in the solar system: it’s literally true, but just as 11 Earths can fit across the diameter of Jupiter, an average September has about 11 times more total tropical activity than an average July. (May is Pluto in this metaphor, but that’s a different column.) July is still very much in the prelude to the late August through mid-October peak of hurricane season.

Here on Earth, at least one Atlantic tropical storm forms in July about 60% of the time. Powerful storms remain unusual, with just nine Category 3 or higher storms, including Beryl, since 1900. Thus, July storms account for less than 5% of historical Atlantic tropical cyclone activity, though they punch above weight at 9% of total U.S. landfall activity. Interestingly, U.S. landfalls are more common at either the beginning or end of July, with a pronounced doldrums dip mid-month. Prime days, indeed.

Where do they come from? That mid-July gap exists for a reason. At month’s end, the primary spark for developing storms is primarily tropical waves, a change from a mix of Central American Gyres, stalled fronts, and tropical waves at the beginning of July. The frequency of the first two modes of development drops off faster than the latter picks up, so there’s typically an opportunity to go to the lobby and have yourself a treat while the reels change. Maps show many more tropical development points east of the Lesser Antilles than in June, but many fewer than in August and September.

Where are they going? As a bridge month between weaker early-season activity forming closer to the continental U.S. and potentially stronger peak season activity forming farther away, July doesn’t play clear favorites with landfall risks. Historical odds do tilt towards the Gulf Coast, especially Texas; there’s also a smattering of past landfalls farther north along the Southeast U.S. coast, though the East Coast of Florida has seen only a couple of hurricane hits in July in the last 170 years. Overall, historical chances of at least one July named storm or hurricane landfall in the continental U.S. are about 30% and 15%, respectively. In Florida, those odds are about 10% for a named storm and 5% for a hurricane. So, July landfall activity isn’t that uncommon, but it’s not exactly the norm, either.

Heavy hitters and worst-case scenarios: Like June, July lags in terms of U.S. major hurricane landfalls, with just three in the historical record since 1851. The most recent of these is Category 3 Hurricane Dennis in 2005, which struck between Destin and Pensacola with 120 mph sustained winds, tied for the month’s strongest U.S. landfall. Dennis caused extensive wind and water damage in the western Panhandle, and its angle of approach, size, and intensity caused record-setting storm surge extending that affected much of the Florida Gulf Coast. Sadly, Dennis caused 15 deaths in the United States, and another 39 in the Caribbean. Between Dennis and Category 1 Hurricane Cindy, which struck near New Orleans, 2005 was the only year with two July U.S. hurricane landfalls.

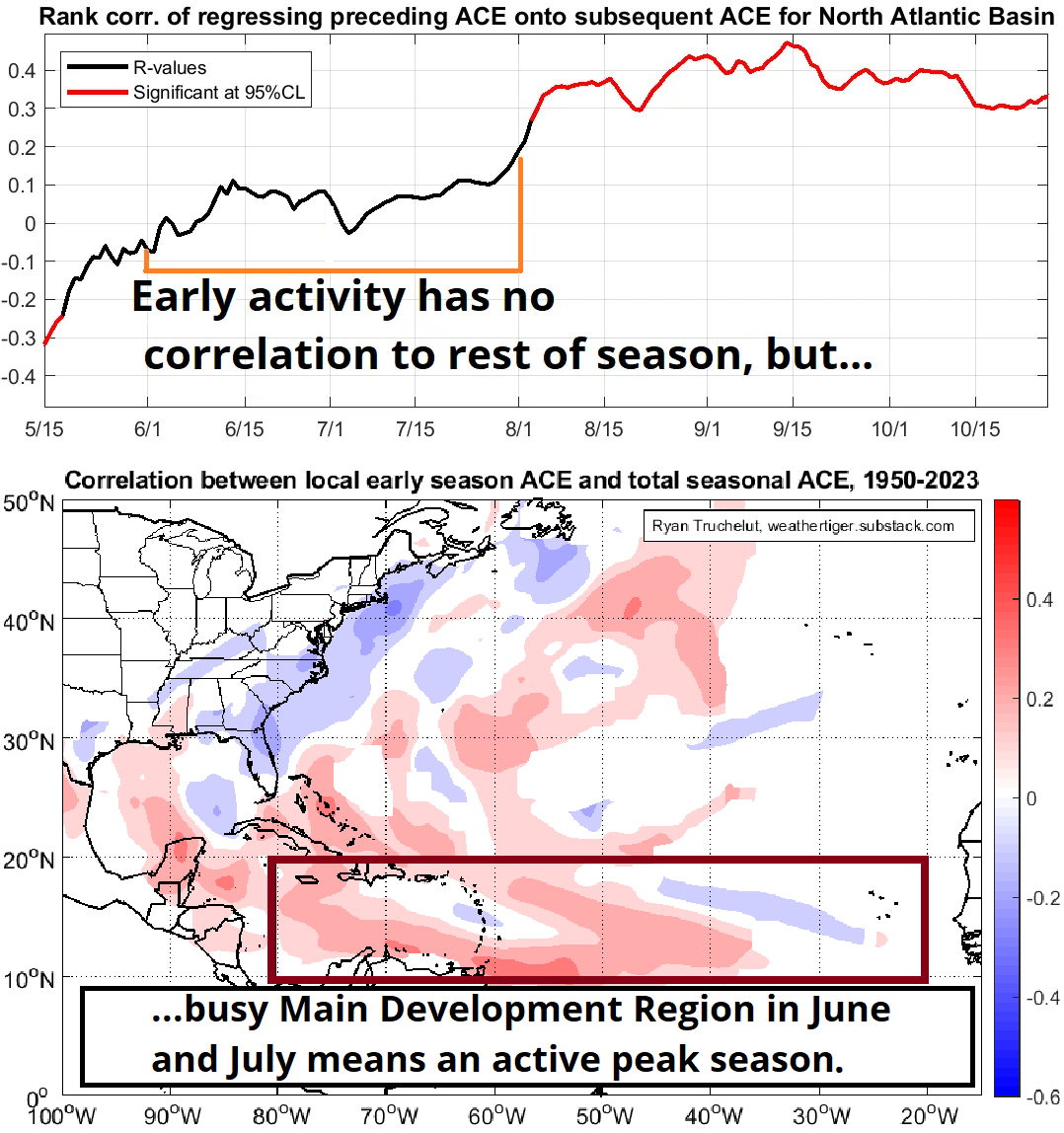

What it means: The total amount of storm energy that occurs over all of Atlantic prior to August does not predict how busy the August-September-October peak of the season will be, but, as I’ve discussed previously, years in which a hurricane develops in the Tropical Atlantic or eastern two-thirds of the Caribbean in June or July are all above average or hyperactive in the peak. The favorable conditions that yielded Beryl are likely to return at some point in August, and that will probably yield an extended burst of hurricane activity. WeatherTiger’s real-time forecast remains for around twice the amount of storm activity in a normal hurricane season.

Bottom line: enjoy the break, but don’t get cocky, kid. Take it from someone who is a big fan of astronaut ice cream and has contracted coronavirus at EPCOT’s Mission: Space on two non-consecutive occasions1, a July in low orbit doesn’t mean we’re not heading for an intergalactic/planetary peak of hurricane season. Stay ready to react.

And finally, grading the mariners: C+. “Stand by” isn’t much of a stance, and neither is awarding the crew of the H.M.S. Pinafore a C+. If you asked me to summarize July hurricane history with a breezy, ambiguous rhyme, I’m definitely going with “July, keep watching the skies.”

Unfortunately, this is literally true! The second time was a few days ago, which explains why this week’s column is late and not that good. Sorry.

Recover soon from Covid! We definitely need you this storm season!

Disney in summer = incubus of viral plague. Hydrate, and keep on truckin’, Doc!