Hurricane Beryl Forecast and Weekly Column for July 3rd

Jamaica, the Yucatan, and the western Gulf are next for powerful Hurricane Beryl. But what does it mean for the rest of 2024?

This post is outdated. Click here to read our new forecast as of 5 p.m. Friday.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get comprehensive daily tropical briefings, weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year. If you enjoy reading this newsletter, please consider supporting.

Reality: it hasn’t felt very realistic lately. Hurricane Beryl further deepened the uncanny valley that is life in A.D. 2024 this week, brazenly defying the norms of hurricane history as it plows west across the Caribbean. While Beryl remains a formidable hurricane today and poses a serious threat to the western Gulf of Mexico this weekend, its implications for the season ahead are also sobering.

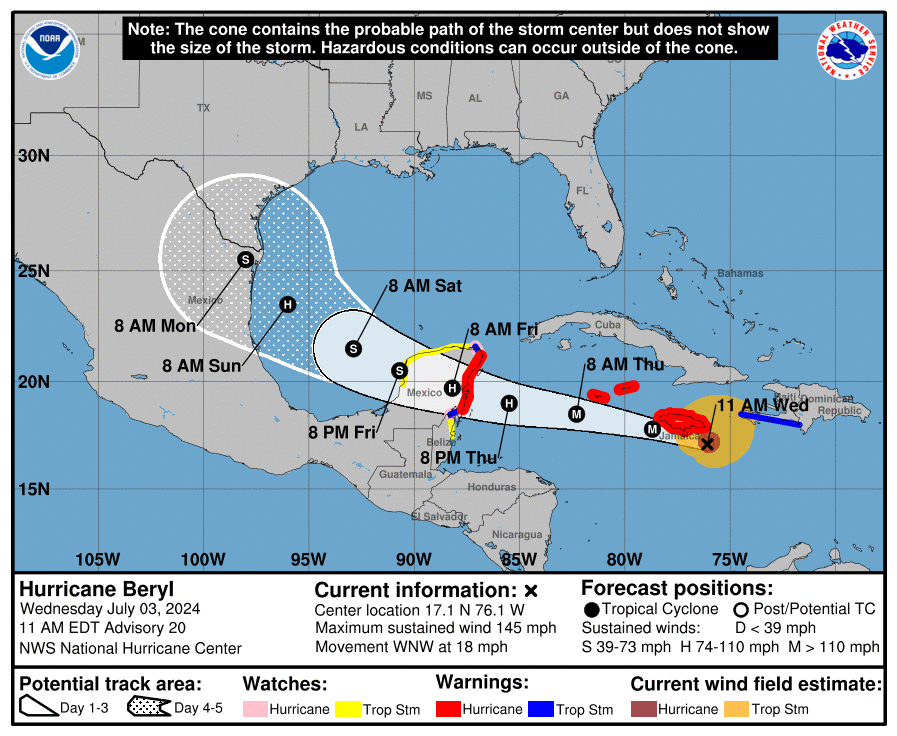

As of the 11 a.m. Wednesday advisory from the National Hurricane Center, Beryl is still a Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph, nearing the southern coast of Jamaica and moving west-northwest around 20 mph. Recent Hurricane Hunter data show that Beryl is finally weakening as increasing wind shear takes its toll, with minimum pressures rising, the formerly clear eye clouded over, and diminished winds on the hurricane’s southern half. Unfortunately, the still-vigorous northern eyewall will pass exceedingly close to southern Jamaica on Wednesday afternoon, and the wind and surge threat there is the most serious in a decade or more.

As Beryl scrapes the mountainous coast of Jamaica, land interaction plus shear spurred by strong low-level trade winds should further disrupt the hurricane’s circulation, and Beryl will likely shed two or three categories by late Thursday as it continues towards the Yucatan peninsula. That still puts the Yucatan coast of Mexico in line for a Category 1 or 2 hurricane landfall, though as of now the worst conditions look to remain south of the more populated Cancun area.

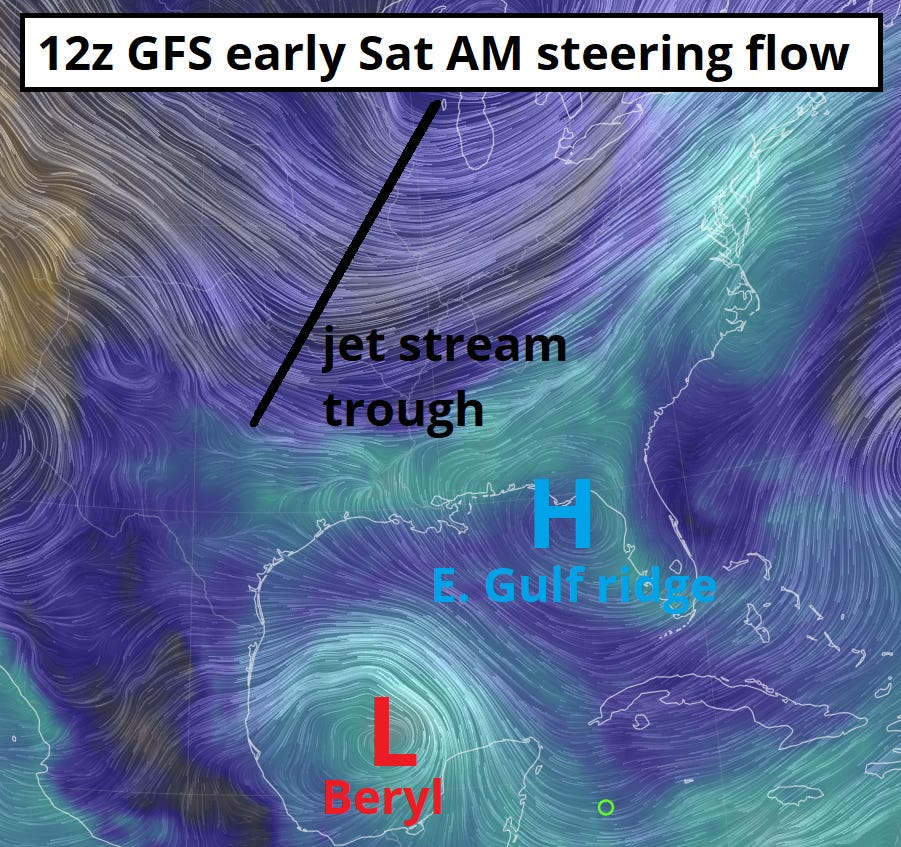

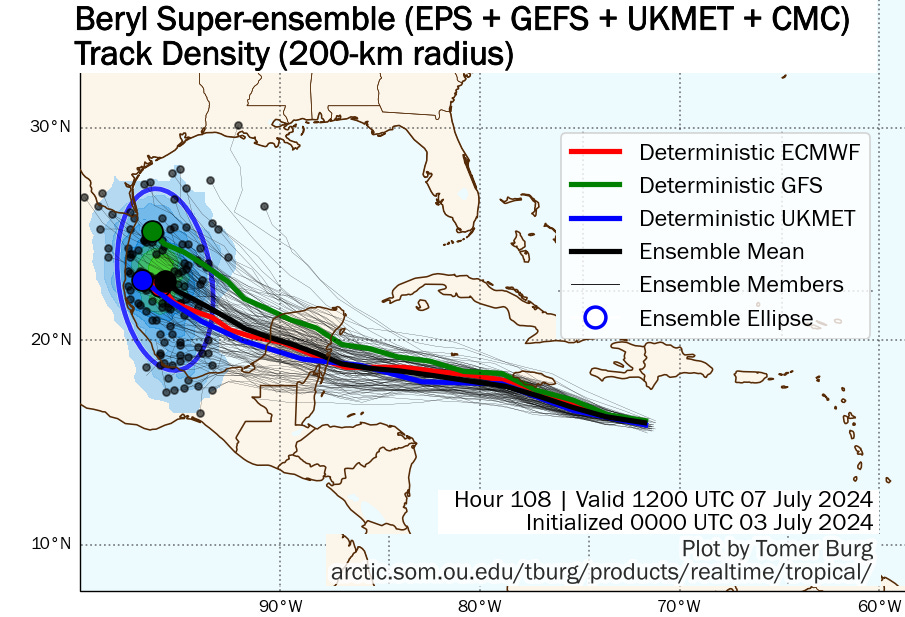

Precisely how much Beryl weakens over the next couple of days is key for the hurricane’s Gulf endgame. A weaker Beryl would likely move westward across the Yucatan, spend more time over land, and probably pass through the southern Gulf as broad, disrupted system. If Beryl doesn’t weaken as much, a developing dip in the jet stream over the U.S. Plains could connect with the storm earlier and impart a more northwestward track into the western Gulf. A protective ridge of high pressure will stay in place over the eastern Gulf, so Beryl remains zero threat to Florida, but a more northerly track would give Beryl more time to reconstitute itself and potentially put Texas in line for a hurricane landfall threat by Monday.

Overall, a track towards the Mexican rather than western U.S. Gulf Coast is the most likely outcome. While model guidance for Sunday’s position for Beryl ranges from the far southern Gulf of Mexico to approaching southern Texas, many of the northern scenarios show Beryl moving over or even north of Jamaica in the short term, which is not going to happen. Interests in Texas should monitor Beryl’s progress, as rain, wave, and rip current impacts are certainly expected there no matter what. However, the most probable outcome is that Beryl makes its final landfall along the central or northern Mexican Gulf Coast by early Monday, perhaps as a strong tropical storm or low-end hurricane. Development prospects for a tropical wave in Beryl’s wake have diminished as the system has choked on Beryl’s exhaust, so thankfully the Tropics should calm down next week.

Of course, it’s hard to trust that Beryl will behave predictably, as its entire history has made a mockery of convention. When Beryl peaked at Category 5 intensity on Tuesday, it became not only the earliest Category 5 in Atlantic history, but both the strongest June and strongest July hurricane on record. This is especially remarkable given that any kind of early-season tropical development is rare in the eastern Atlantic; prior to Beryl’s Category 4 swath of destruction through the Windward Islands, only four hurricanes had ever struck the Lesser Antilles prior to August, none stronger than a Category 1.

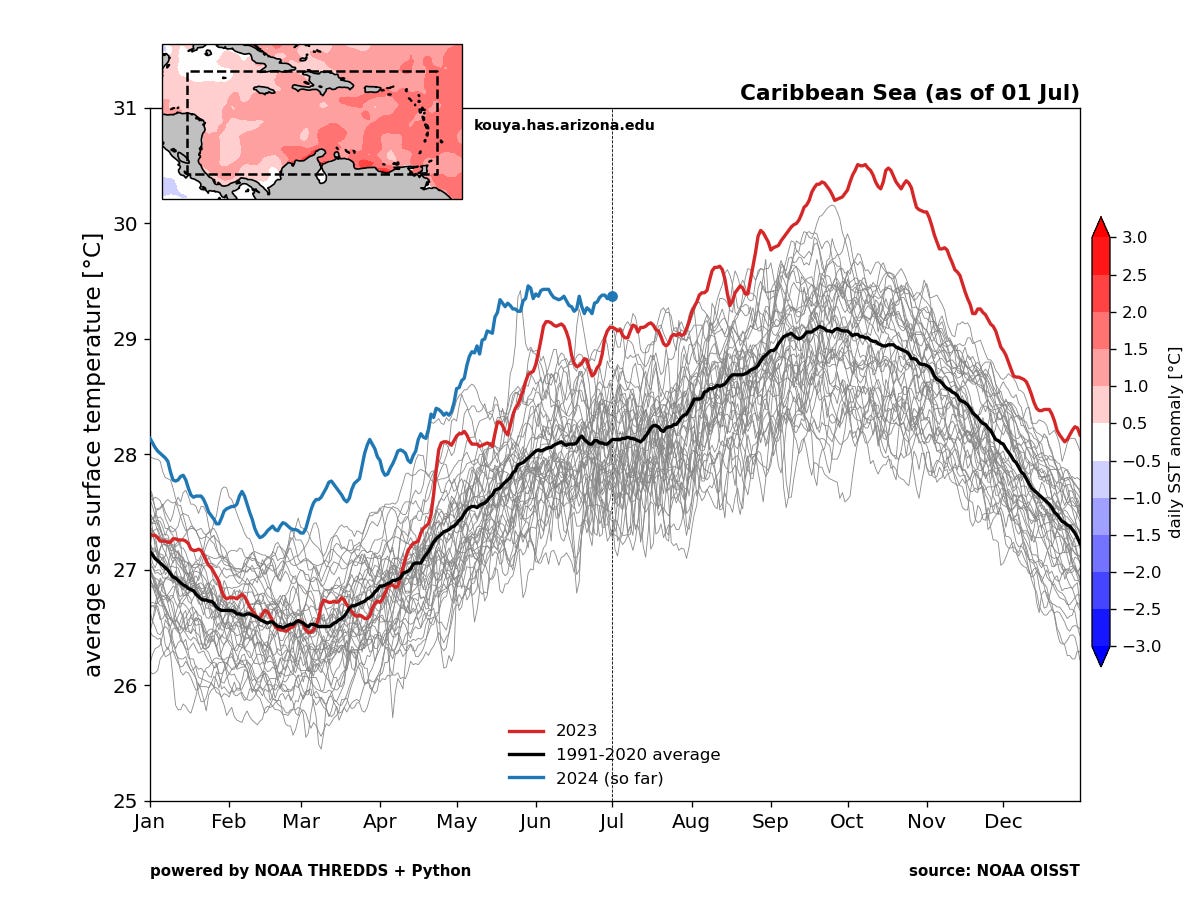

So, why is Beryl a climatology unto itself? Well, just like dogs don’t know Beggin’ Strips aren’t bacon, hurricanes don’t know what month it is on the calendar. All it “knows” is what is in front of it now: waters in the Tropical Atlantic in the middle and upper 80s, temperatures that would be well above normal for the peak of hurricane season in August or September. Atmospheric conditions along Beryl’s path provided favorable low- and mid-level moisture to spur convection and immaculate upper-level outflow to ventilate that strong thunderstorm activity, ideal conditions for a hurricane to rapidly extract the extra thermodynamic potential available to it. Play September games, win September prizes, basically.

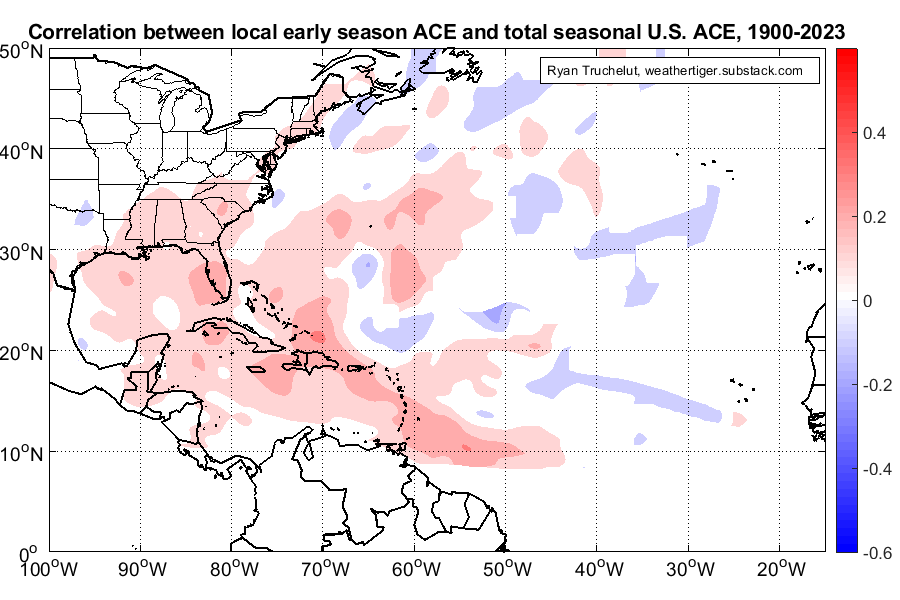

While Beryl is itself a devastating storm, much of the intense agita it has provoked is more about what this norm-shattering hurricane means for the rest of the season. True, there is no relationship between how much total tropical activity occurs before August and how much happens later. However, the blaring exception to the rule is if that activity occurs in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region, the area south of 20N and east of 80W that doesn’t tend to light up until mid-August, but is a common source of many of the strongest and most impactful storms in the peak of the season.

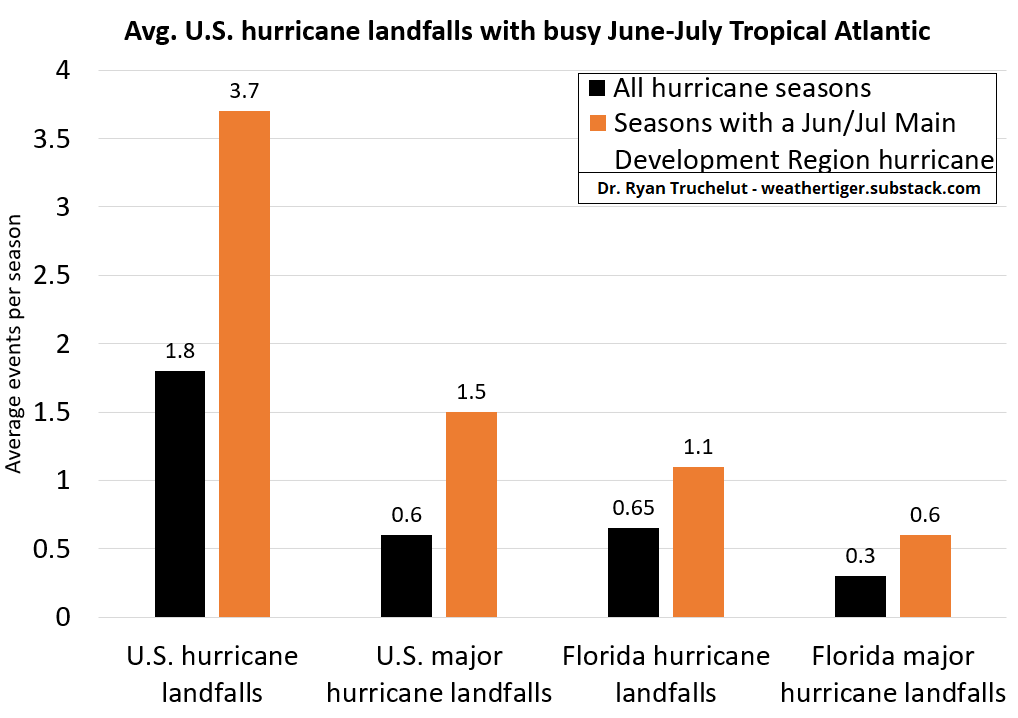

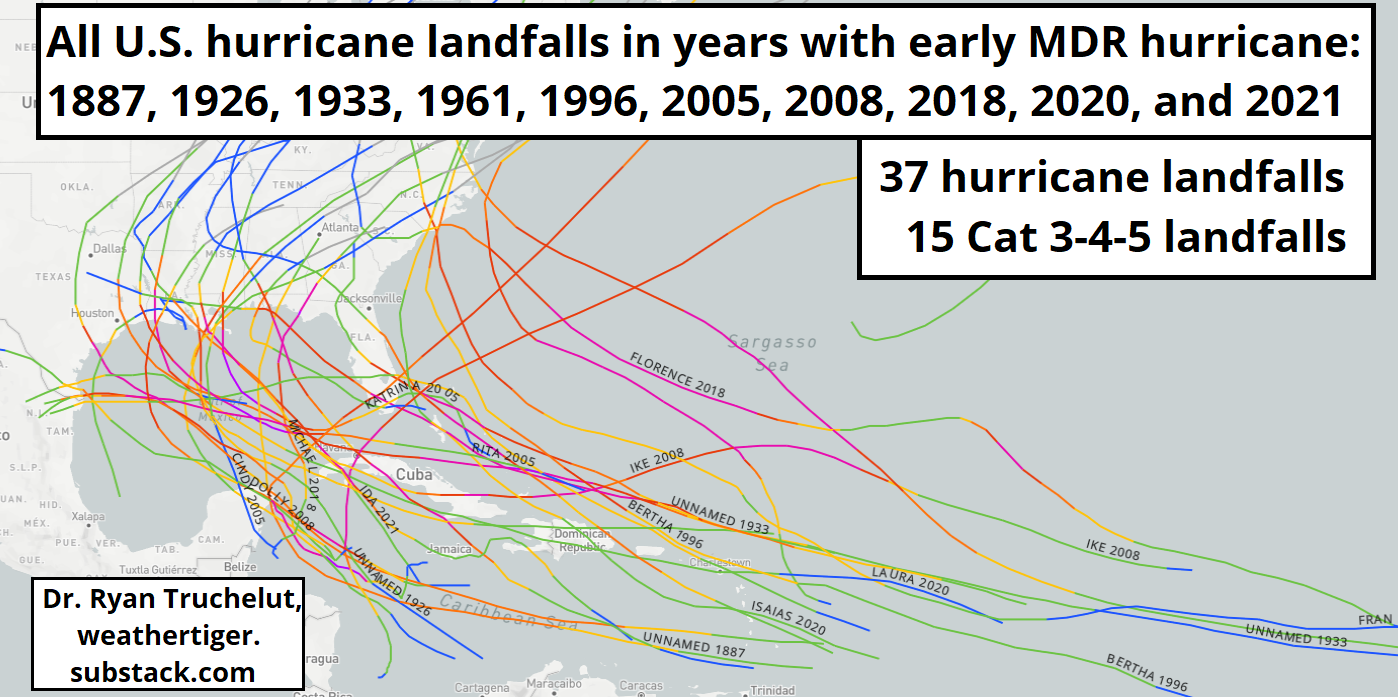

In these areas, significant June or July tropical activity is on average linked to elevated activity both for the season as a whole, and specifically for U.S. landfalls. In the last 150 years, there are ten seasons in which a hurricane formed in the Main Development Region before August: 2021, 2020, 2018, 2008, 2005, 1996, 1961, 1933, 1926, and 1887. All of those years were above-normal hurricane seasons, averaging almost double the long-term mean for Accumulated Cyclone Energy. Thirty-seven continental U.S. hurricane landfalls, fifteen of them major, lurk in those ten seasons, two to two-and-a-half times more than normal. Four of the ten recorded a major hurricane landfall in Florida, with two major hurricane landfalls in Florida in 1926 and 2005.

Now, as we know, the future is not necessarily like the past. Beryl doesn’t guarantee any particular outcome for the rest of 2024, but the numbercrunch on similar historical cases squares with WeatherTiger’s (and everyone’s) expectations for an extremely busy season ahead based on the totality of evidence. That doesn’t mean you need to live in an Inside Out 2 anxiety cyclone for the next four months, but it does mean that you should do the things you can do now to prepare before the inevitable conepanic hits. So, trim those trees, know where you would go if you need to evacuate, make sure your hurricane kits are in order, and as always, keep watching the skies.

I always wonder where these wind measurements come from. I know about ships and buoys and dropsondes however when the storms pass airports I just check the Metar data and there is always a significant difference. I had this discussion with a NHC forecaster after Michael hit Mexico Beach about an actual land station very close that never showed winds nearly as strong. The forecaster took my questions as an afront and got upset that they were being questioned. That interchange did not increase my trust in NHC.