Endless, Nameless: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for October 11th

A non-tropical low brings impacts to Florida while the Cape Verde season goes into overtime in the eastern Atlantic.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

In “Romeo and Juliet,” Shakespeare opines that “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Unfortunately, the pillars of Western literature are silent as to whether the functional equivalent of a weak tropical storm without a name is just as annoying, merely 83% less anthropomorphized. Yet that is the weather situation Florida and the northern Gulf Coast finds itself in today, as a frontal low brings similar rain, severe weather, and wind impacts as a quick-moving, weak tropical storm.

This system originated a couple of days ago as a tropical disturbance in the southern Gulf, and has since rolled up the remnants of Eastern Pacific’s Tropical Storm Max and merged with a potent stalled front over the northern Gulf of Mexico. As fronts divide warmer and cooler airmasses and, by definition, tropical cyclones must be free of temperature gradients across the storm, structurally this low does not qualify to be named as a subtropical or tropical storm by the NHC. (Naming rights may be available through the International Star Registry, if any of you aunts and grandmas out there are looking for easy Christmas gift ideas.)

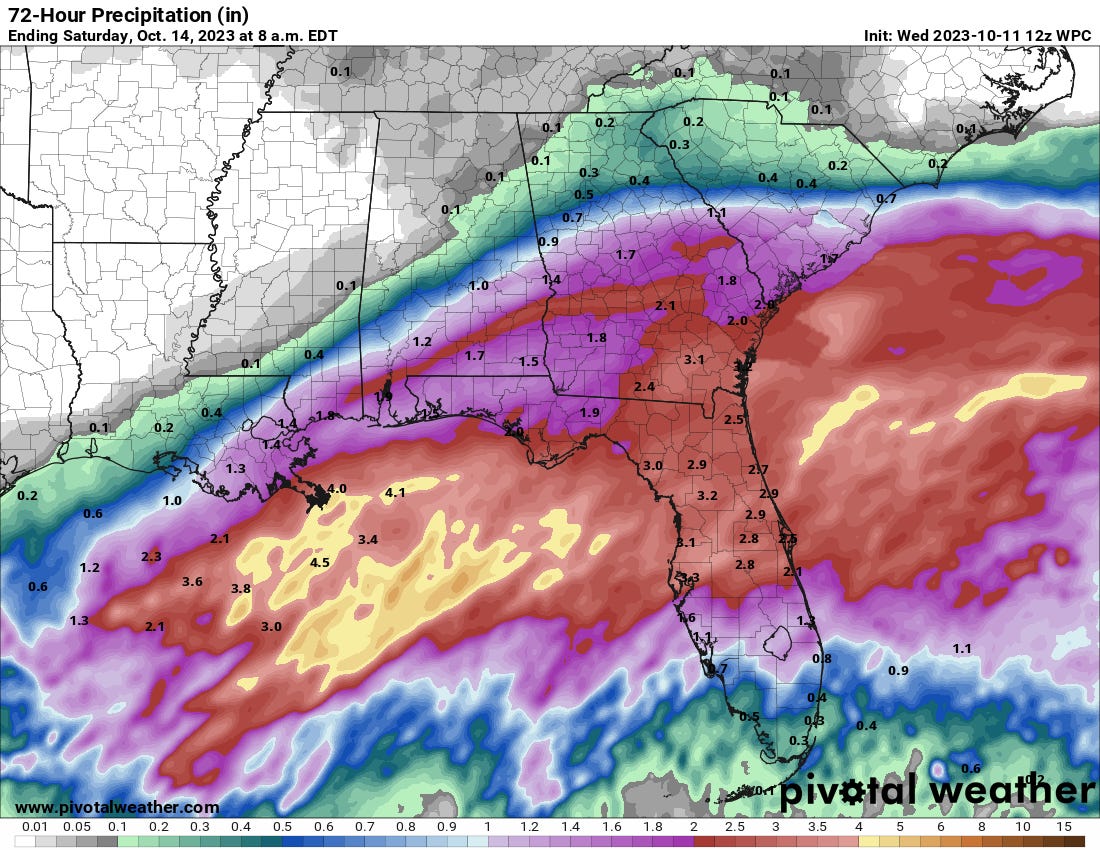

Structural strictures aside, nasty weather is nasty weather, and Florida will have that to deal with over the next few days. Precip is already spreading across the northern Gulf Coast as of Wednesday afternoon, and eastern Louisiana, North and Central Florida, and South Georgia are expected to see 1.5-3”+ of intermittently heavy rain through early Friday. Rainfall will be heaviest overnight Wednesday into Thursday with clearing by noon Thursday in North Florida, and Thursday evening in Central Florida. North-central Florida is also at a particular risk of seeing a few tornadoes or severe thunderstorms.

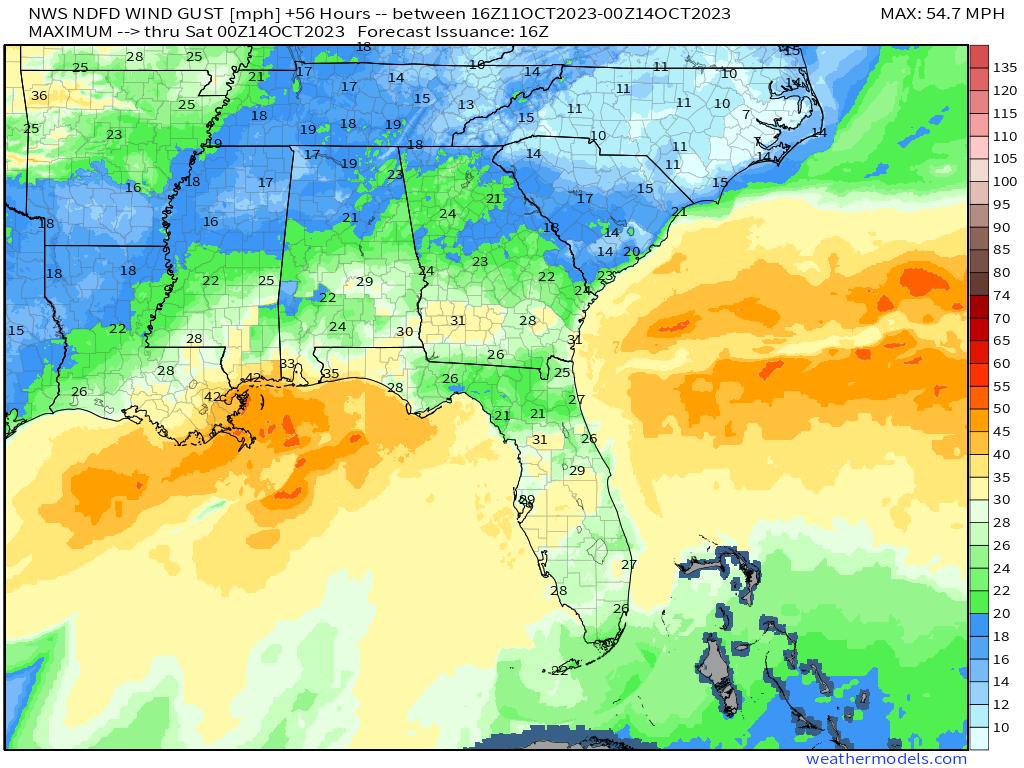

This no-name low won’t be any kind of damaging wind event inland, although I wouldn’t rule out toppling a few 12’ skeletons with occasional wind gusts above 30 mph. Wind gusts along the immediate coast and offshore may exceed 40 mph along the central and eastern Gulf Coast, and Gale Warnings are in effect from eastern Texas to the Big Bend. Onshore winds may also cause elevated tides around a foot above normal for Panama City east to Tampa. In general, expect weather conditions in Florida through Thursday to be consistent with a nameless irritant, but nothing more.

Elsewhere in the Tropics, the Cape Verde season goes on, long after the thrill of cyclogenesis is gone. Tropical Storm Sean has developed about 1,000 miles west of Africa, which is the farthest east a named storm has ever formed in the Tropical Atlantic this late in the year. Don’t expect much from Sean, as it will likely weaken below storm strength and return to being of the dead in a few days as it moves west-northwest into a region of higher shear and dry air.

Sean may not be a season wrap for the eastern Atlantic though, as a wave to its east, Invest 94L, is also generating quite a bit of convection as it moves south of the Cabo Verde Islands. Steering currents will be slow in Sean’s wake, and it may take a week or more for this wave to eventually approach the Lesser Antilles, should it hold together.

Environmental conditions will be marginal as the usual late-season shear axis takes hold in the eastern Atlantic, but some development of this wave is possible over the next 5 to 7 days. As the 2023 hurricane season kicked off with two unusually early June storms in the eastern Atlantic, the strange attractive factor of ending it symmetrically with two late Cape Verde storms says don’t count this wave out.

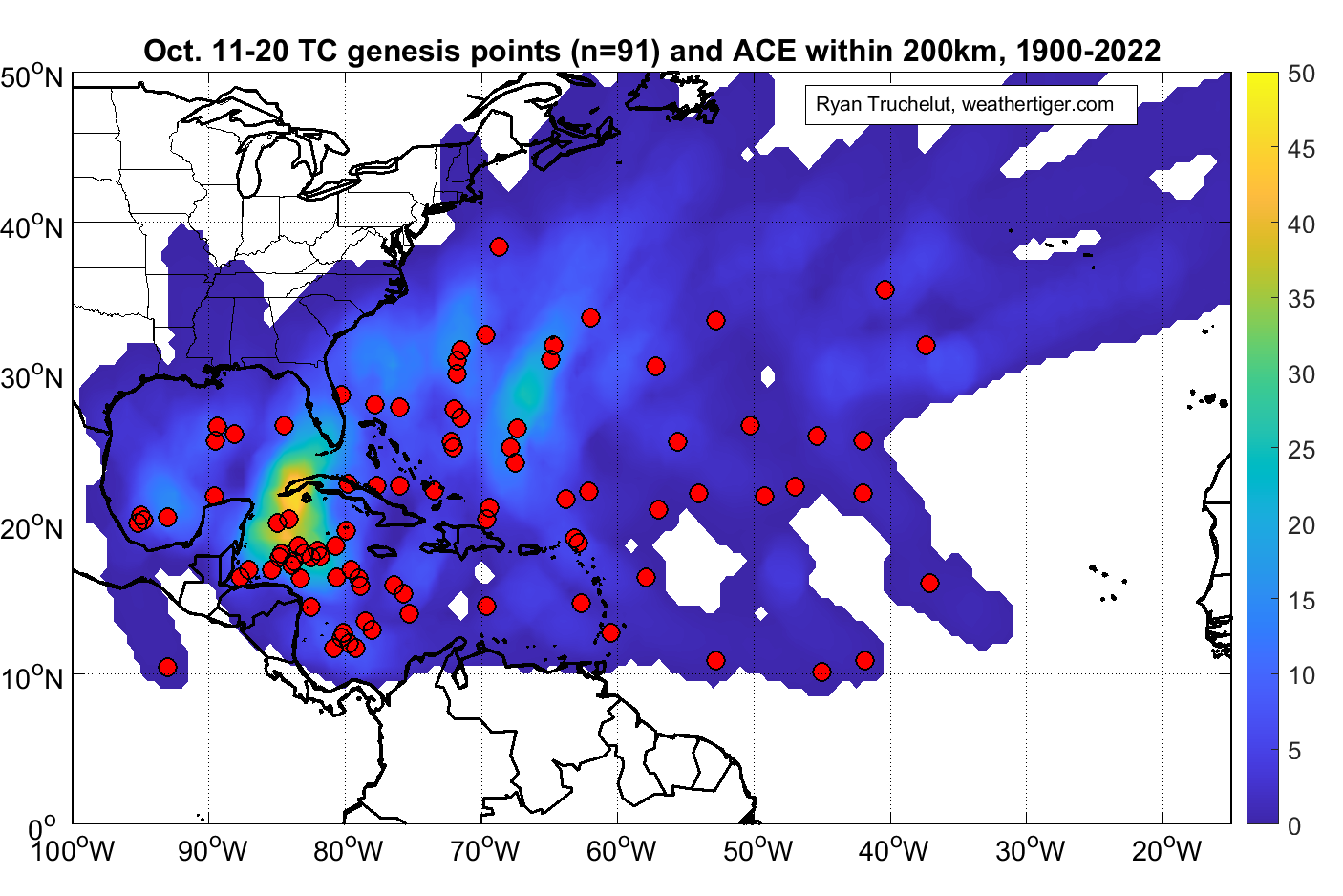

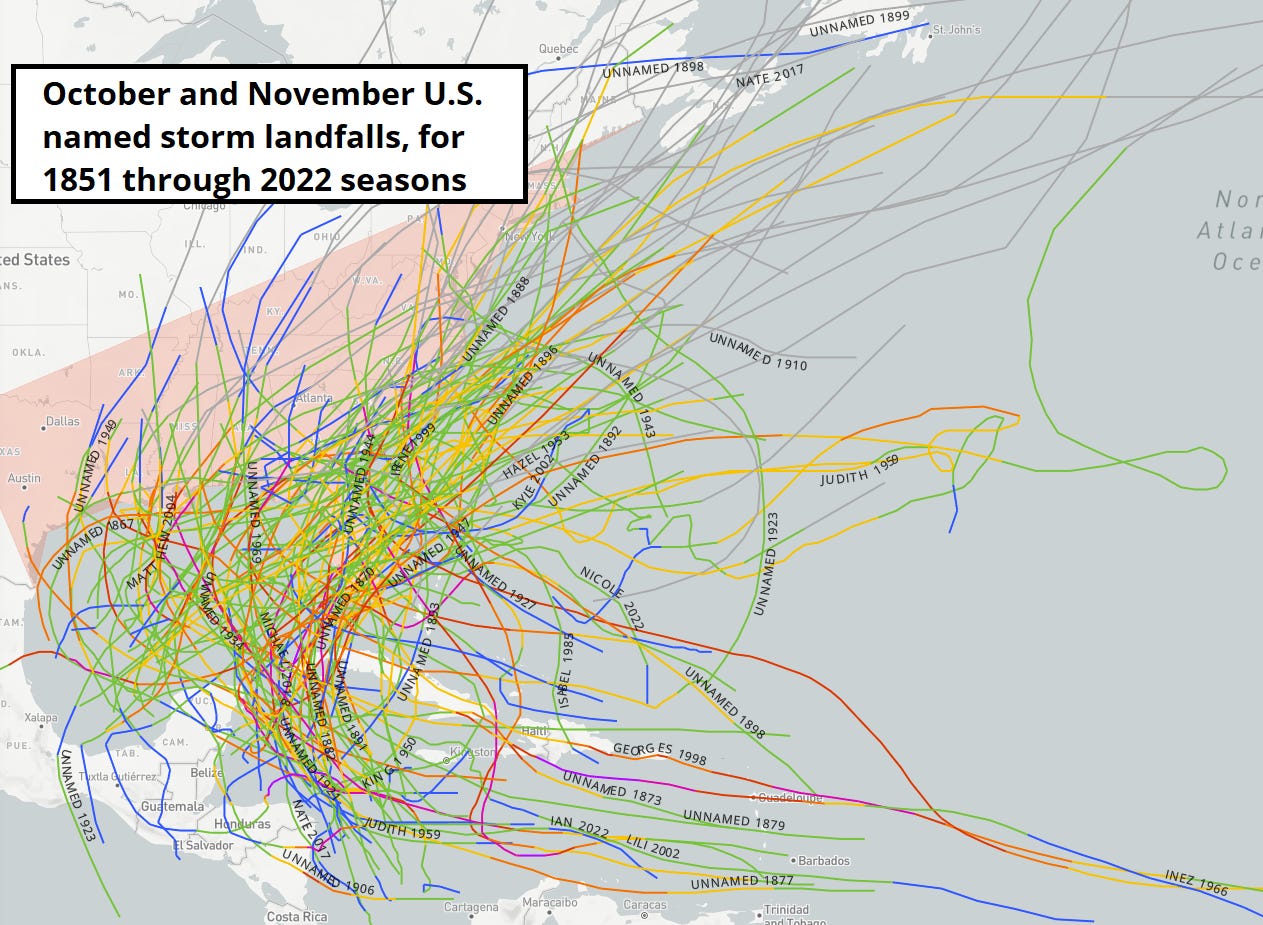

The eastern Atlantic isn’t usually where we focus our attention in the final 20% of hurricane season, as most storms that have made landfall in the continental U.S. in October and November develop in the western half of the Caribbean or in the southern Gulf of Mexico. The good news is that there is nothing going on in the Caribbean today, and a dry airmass is likely to keep things that way for the near future.

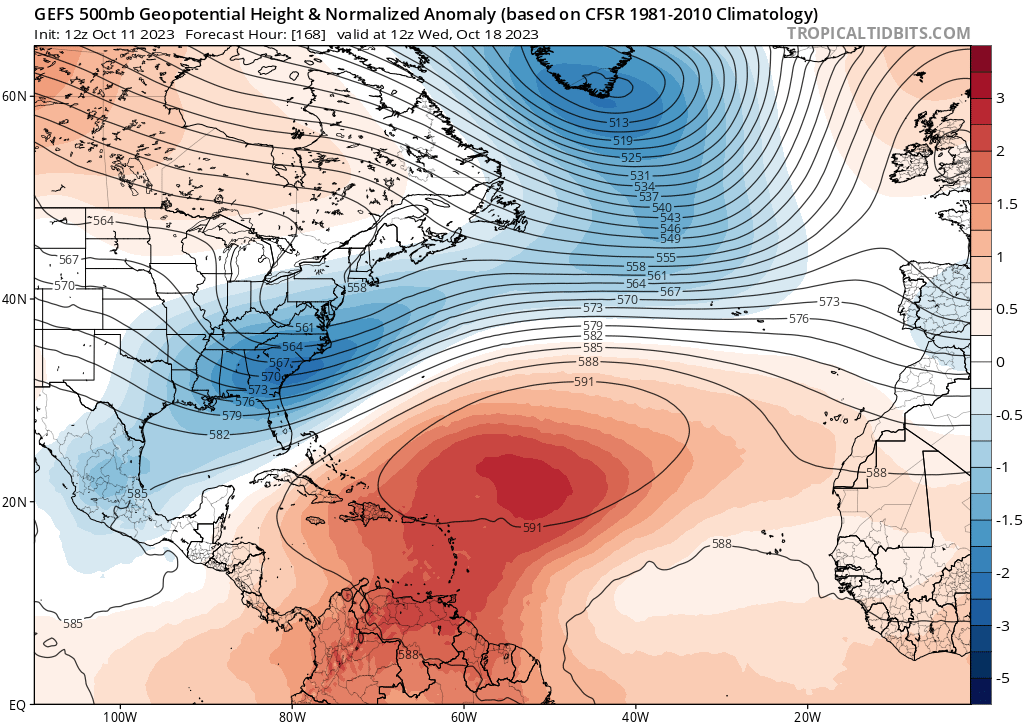

With long-range modeling indicating that a persistent East Coast dip in the jet stream will deliver frequent cold fronts across the Southeast U.S. and into the northern Caribbean for the next couple of weeks, the windows for any potential tropical threats to Florida are quite limited. At this time of year, tropical storms sometimes develop on the tail end of stalled fronts in the Caribbean, then move back north towards the Gulf Coast ahead of the next front. However, that process takes time, and the fronts over the upcoming 10 days are likely too close together to allow a tropical system to congeal.

Still, the Caribbean remains much warmer than average, and with wind shear there favored to be relatively low in the second half of October, I’d be a little surprised (but not shocked) if nothing developed in the Caribbean or Gulf for the rest of the year. Even so, that wouldn’t necessarily translate into a landfall threat, as the historical rate of U.S. landfalls drops off dramatically starting around October 25th.

Of course, Florida has had a tropical storm (Eta 2020) or hurricane (Nicole 2022) landfall in two of the last three Novembers, and if I don’t mention Category 2 Hurricane Kate’s landfall near Cape San Blas on November 21, 1985, you will e-mail me about it. Those storms and late October pattern uncertainty mean that it is still too early to call time on 2023. Overall, for now I’ll take hurricane season being endless in the eastern Atlantic if it stays nameless in the west. Keep watching the skies.