B-B-B-Bret and the Jets: The Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for June 20th

Tropical Storm Bret is not a U.S. threat, but it may be a sign of more unusual tropical weather ahead.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused tropical briefings each weekday, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

The word “unprecedented” gets thrown around a lot in this column, and it annoys me. Like Creed Bratton, adverbs, or fats and sweets on the food pyramid, superlative descriptors like unprecedented should be used sparingly. As a hurricane climatologist by training, I prefer to understand the present through the lens of an orderly past.

Yet befitting the weather’s chaotic neutrality, the past is inadequate prologue, and history provides only slant rhymes to an age of perpetual weirdness. Such is the case once again today, as the Eastern Atlantic sees a potential double dose of tropical development far afield of June norms, while the southeastern U.S. suffers under a bizarre jet stream pattern.

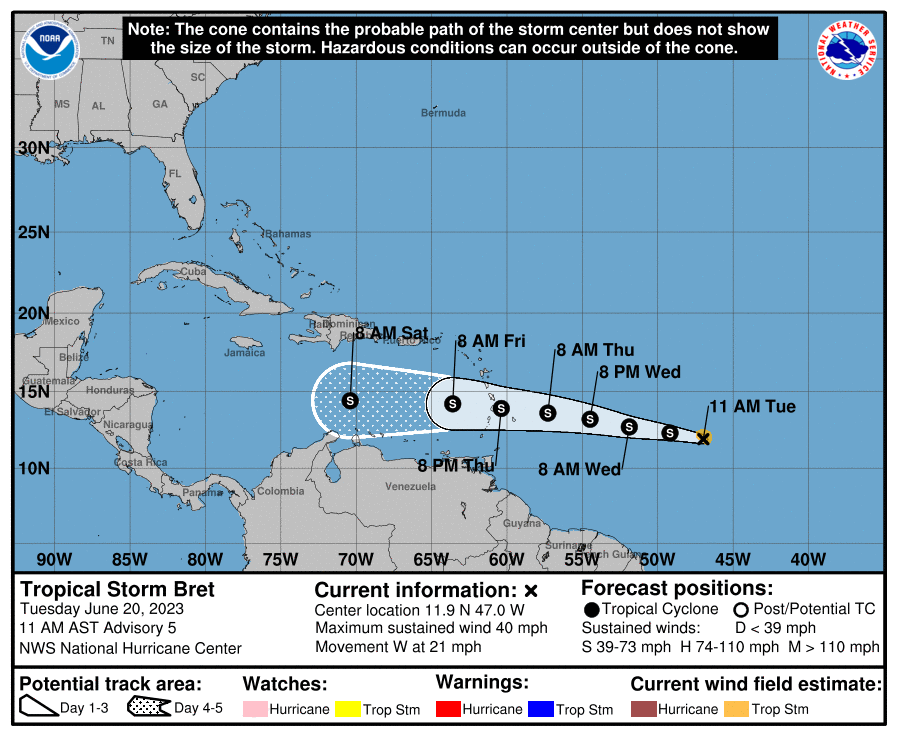

This week’s main offender is Tropical Storm Bret. As of the NHC’s 11 a.m. Tuesday advisory, Bret is about 1,000 miles east of the Lesser Antilles with sustained winds of 40 mph, tracking westward at about 20 mph. This motion is expected to continue into the weekend, and Bret will bring rainfall to the Windward Islands on Thursday and Friday, and potentially to Puerto Rico and Hispaniola on Saturday and Sunday.

Fortunately, Bret is not a threat to the continental U.S. As of mid-day Tuesday, Bret is generating plenty of convection, but the strongest storms are not co-located with the low-level center of circulation, preventing much strengthening thus far. Wind shear will increase as Bret moves into a drier environment; a little more intensification is possible through early Thursday, but Bret should plateau and then weaken thereafter. The NHC is no longer calling for Bret to reach hurricane intensity prior to the islands, and the storm is most likely to dissipate over the weekend in the Central or Eastern Caribbean thanks to unfavorable upper-level winds caused by a trough over the eastern U.S. Remnants of Bret will likely continue west into Central America early next week.

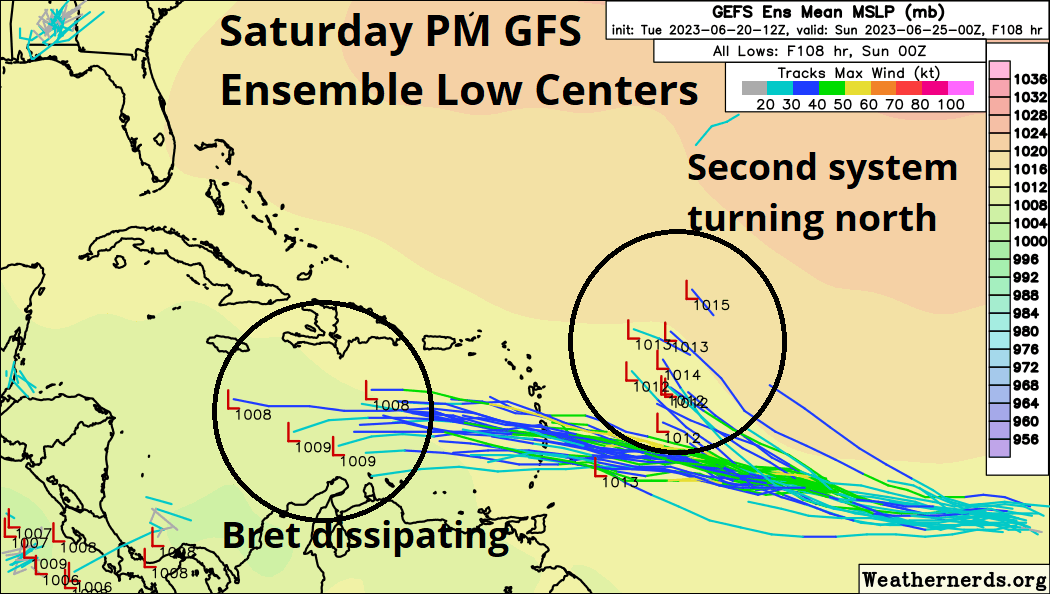

But wait, there’s more! To Bret’s east is yet another well-organized tropical wave, blithely spinning away as if this was early September. Storm activity is a bit anemic with this disturbance (Invest 93L) today, but slow development into a tropical depression or tropical storm is likely by Friday as the wave moves west-northwest through a favorable environment. While the eventual development of Tropical Storm Cindy is probable, this system will turn north over the weekend towards a break in the Bermuda high and should move out-to-sea early next week without affecting land areas.

While the combined impacts of Bret and potential Cindy are expected to be minimal to modest, their very existence is an affront to hurricane climatology. Historical early-season tropical development is clustered in the western Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, with only three cases since 1900 of a storm forming east of the Lesser Antilles in June— the Trinidad hurricane of 1933, Ana in 1979, and the 2017 iteration of Bret. Twin tropical cyclones in the eastern Atlantic in June are, well, unprecedented. Sorry.

And this may not be a meaningless distinction. Years in which the Main Development Region (MDR), stretching from Central America to West Africa, is active prior to mid-July tend to remain busier than normal in the MDR for the rest of the hurricane season. While the relationship is not foolproof, the extreme warmth of the Tropical Atlantic is more likely than not to persist into August and September and give tropical waves a better chance of development in the peak season.

Still, MDR warmth is just one piece of the puzzle, and the same pattern helping create Bret and company is keeping them away from the continental U.S. for now. The last week has been dominated by a strong subtropical jet stream racing from west to east across the Southeast U.S. and into the Atlantic, which has caused the ridge of high pressure (“Bermuda high”) usually over the subtropical Atlantic in the summer months to be quite weak. Weaker tropical trade winds associated with this feeble high have allowed the MDR to heat up to near-peak season levels, while also keeping shear lower than usual. However, the southerly position of the jet is also causing the winds aloft over the Caribbean and western Atlantic that should neutralize Bret and keep a potential second storm away from land.

Closer to home, this bizarre, almost spring-like jet stream pattern dominated by deep cut-off lows over the eastern U.S. is causing significant weather agitation in Florida and much of the Deep South. While daily afternoon thunderstorm activity is typical in June, it’s not typical for Florida to be clocked by organized complexes of severe thunderstorms every 14 hours for 10 days.

The culprit is a rare overlap between both convective potential energy (a.k.a. CAPE, driven by solar heating and abundant in the summer) and strong wind shear (driven by jets, uncommon over Florida in summer). Shear and CAPE are kind of like the Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham of thunderstorms; individually, they can produce impressive work, but when they come together, the results can be truly explosive.

In this case, a sheared environment has caused thunderstorms to be able to sustain themselves over much longer timeframes than usual, triggering damaging winds and the localized rain totals of 6-12”+ or more seen in Pensacola and elsewhere across the Big Bend over the last 7 days. Look for this wet and stormy pattern to wind down for Florida heading into the weekend as the cutoff low finally moves away, the jet stream retreats north, and the atmospheric Mac attack breaks up. (Paid supporters, your three-month Florida temperature and precipitation outlook is on the other side of the paywall.)

Overall, it’s too early for MDR storms and way too early for me to be tapping into Key Lime Lacroix stockpiles to write MDR storm forecasts, yet here we are. The good news is that Bret is not a U.S. threat, but the bad news is that, to the chagrin of meteorologists, we remain well off the beaten path of weather history. What can be done but to keep watching the skies?

July-August-September Florida Temperature and Precipitation Outlook (Subscribers Only)

The latest outlook for Florida temps and precip is for conditions not too dissimilar to an average summer, albeit with a bias towards marginally wetter than average and slightly warmer than normal conditions. The median forecast outcome is about 105% of normal rainfall and average temps +0.8F warmer than long-term norms for July 1 through September 30. One notable difference in our model versus climatology is that the odds of a significantly wet summer (130%+ of normal) is about double the long-term average probability (10% vs. 5%).

I love your reports! I always have a question whenever I hear a fact like, only three tropical storms have formed in the eastern Atlantic since 1900. How do they know this from an era before radar? When did satellite photos of the atmosphere over remote areas of the Atlantic begin? Maybe this would be a good answer to put in one of your posts.

There is a pool of abnormally cold water south of west Africa on the equator. Sort of an Atlantic La Niña. Will this have any effect on this hurricane season?