The Weekend State: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for August 29th

Why late August has been so eerily quiet in the Tropics, and how that may change in early September as the Atlantic starts to perk up a bit.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get daily tropical briefings, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions.

A July Category 5 hurricane in the Caribbean. Aurora in Florida. The Houston derecho. An earthquake in Tewksbury, New Jersey. Twin EF-2 tornadoes ripping through Tallahassee.

There’s been no shortage of extreme and rare natural phenomena on our planet in 2024. But now, it’s time for the most unusual, unforeseen, bizarre weather event yet: the Labor Day weekend without an immediate U.S. hurricane threat.

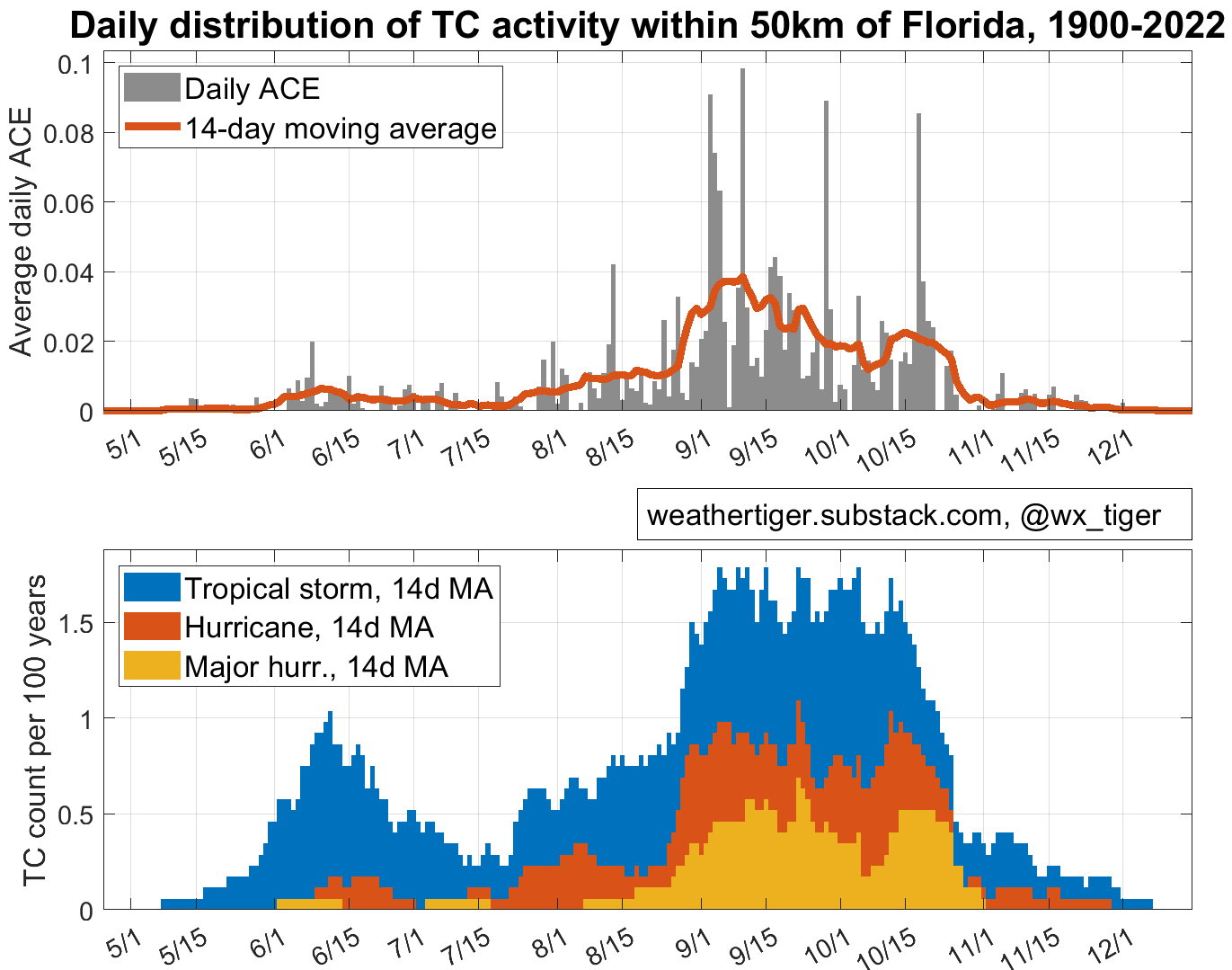

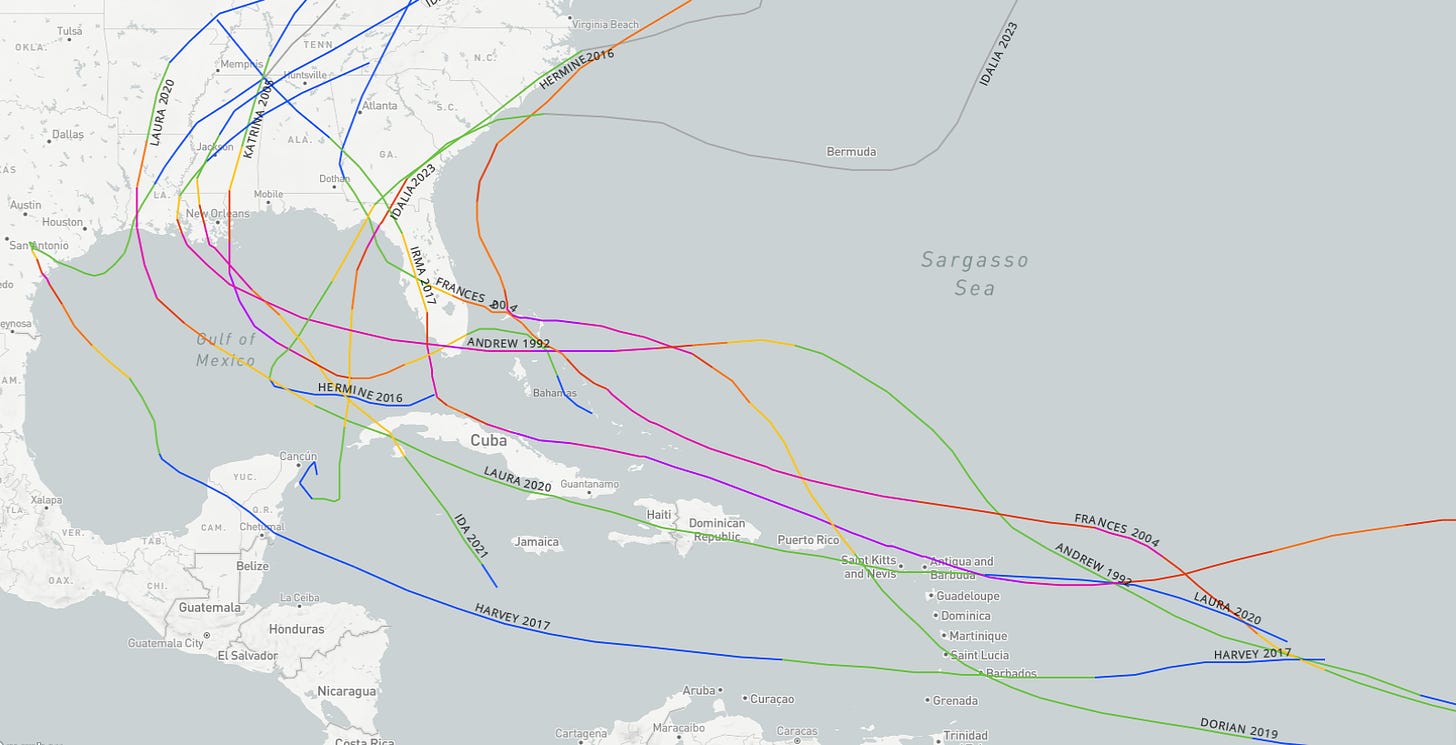

From Frances to Irma to Dorian, Labor Day weekend is typically either a time of maximum agita, or licking wounds following a recent wallop like Andrew, Katrina, Hermine, Harvey, Laura, Ida, or Idalia. The strongest-ever U.S. landfall even bears its name—the Labor Day Hurricane that bisected the Middle Keys with 185 mph sustained winds in 1935.

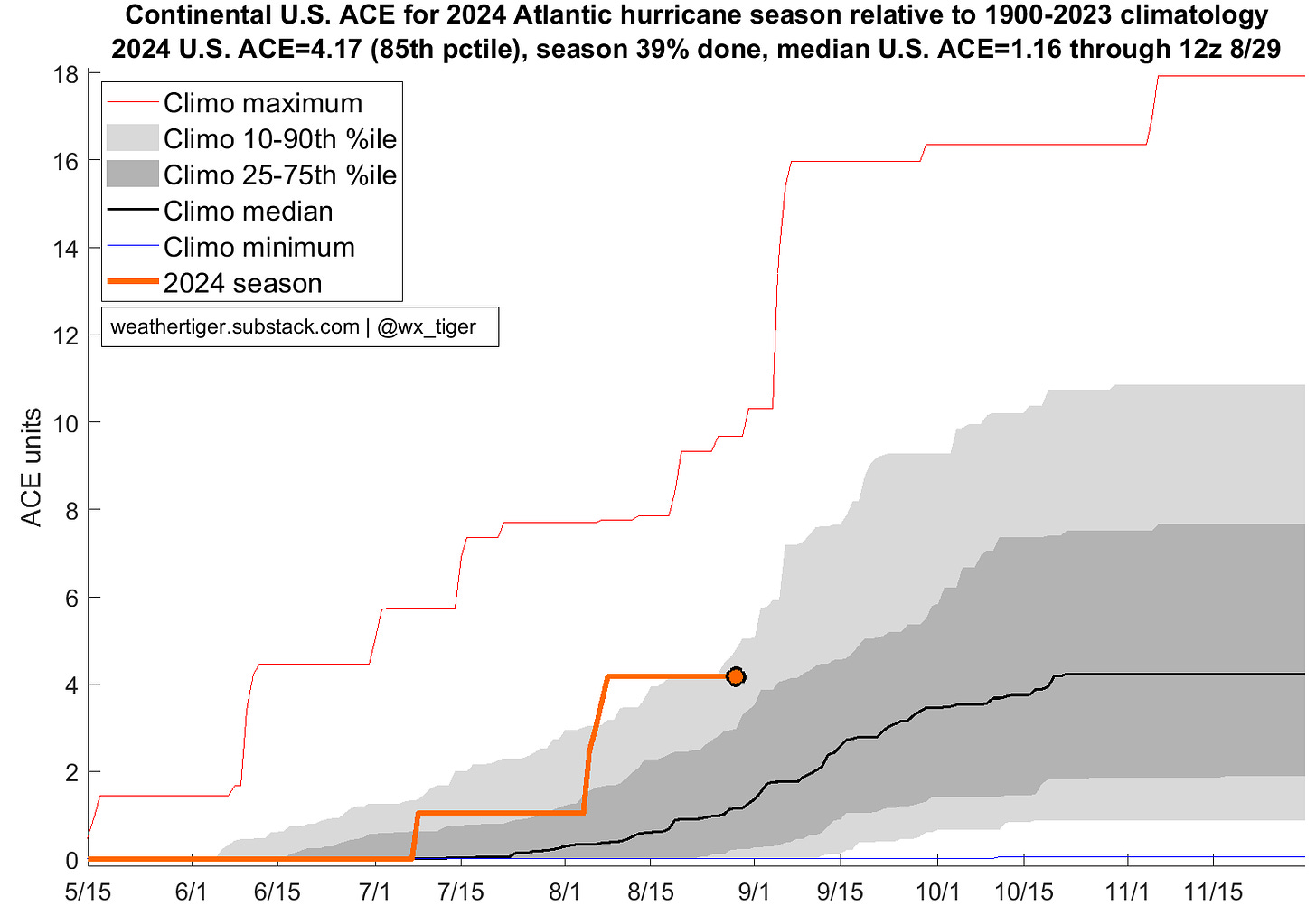

This year, contrary to high expectations, there have been no named storms in the Atlantic since Ernesto dissipated ten days ago. That is a meaningful absence, as about 15% of historical U.S. landfall activity occurs in the two-week period between August 20 and September 2 alone. The fact that we’re neither hunkering up nor down right now doesn’t mean things will permanently stay quiet (more on that later), but opting out of this chunk of hurricane season is valuable.

What’s been killing off potential storms? Well, I can tell you that every hurricane forecaster and researcher is more than a bit flummoxed trying to figure it out. Let’s take a look at possible suspects, murder mystery dinner theater style.

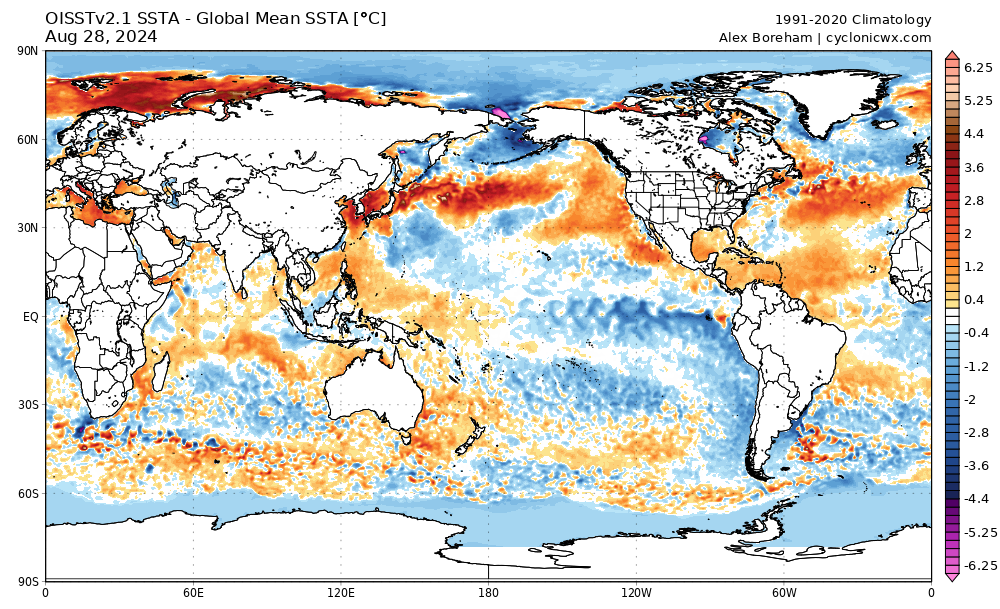

El Nino/La Nina: Generally, an El Nino, or anomalous warmth in the central Equatorial Pacific, means fewer and weaker Atlantic hurricanes, and La Nina means just the opposite. An anticipated 2024 La Nina has been slower to get going than expected, but the Nina/Nino region is still notably cooler than surrounding Pacific, and western Atlantic shear has been low. Doesn’t seem like this is the problem.

Atlantic sea surface temperatures: Over the last couple of weeks, a terminally online brainworm that the Atlantic is “rapidly cooling” has taken hold. This is far from reality, as the Atlantic’s Main Development Region remains tied with 2023 for the warmest ever, and has heated up even more in the last couple weeks. From the Gulf to the Caribbean to the eastern Atlantic, broad and deep warm water is waiting to provide an abundant energy source to any disturbances able to take advantage.

However, there may be a germ of truth in this misconception. A region of the Atlantic along the Equator south of West Africa is a little cooler than nearby waters, which may be pushing another key to hurricane development out of joint.

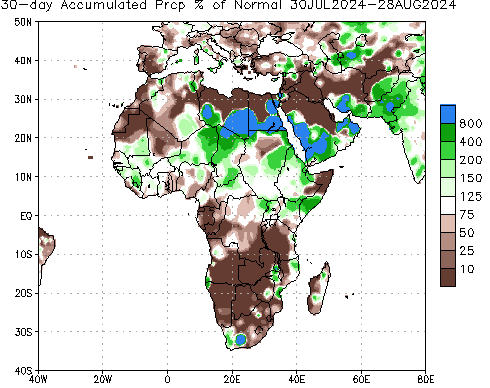

Tropical convection and tropical waves: There have been plenty of tropical waves, the seeds from which hurricanes develop, crossing Africa over the last few weeks. However, possibly because of the higher than normal temperature contrast between sub-Saharan heat and those milder waters south of Africa, the zone of clashing winds those waves follow has been much further north than usual in August. This summer has even brought heavy rainfall to normally parched southern Egypt and Libya, where thunderstorms are as out of place as a Dave & Buster’s at a Florida State Park.

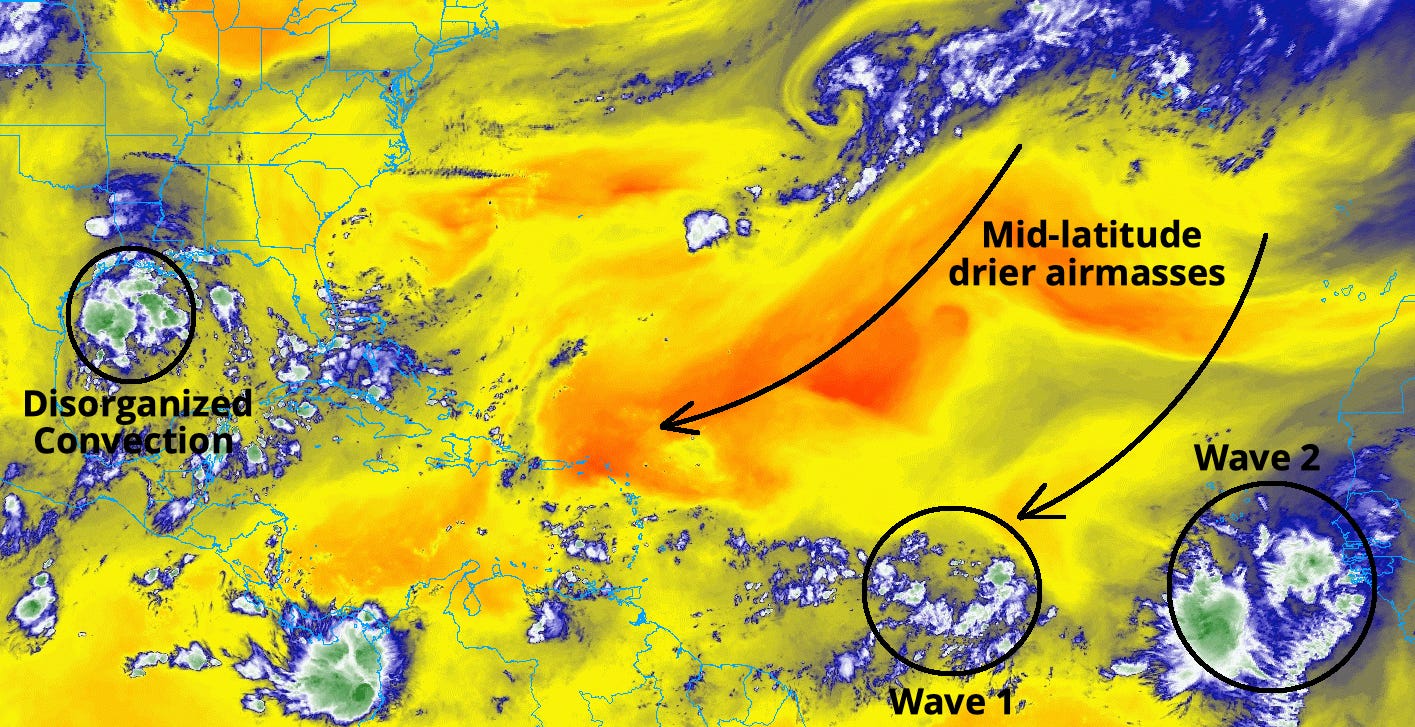

That means rather than smoothly rolling off the coast and proceeding west, farther north waves have gotten tangled up in powerful West African monsoon winds, smearing out their initial rotation and preventing eventual development. Their northward displacement also means waves emerge over cooler waters and closer to the unfavorable influences of mid-latitude weather, bringing us to our final suspect.

Mid-latitude influences: Dry air is a typical problem in the Tropical Atlantic in August, particularly when mingled with Saharan dust. However, desert dust hasn’t really been the hold-up recently, but rather repeated dips in the jet stream over the Northeastern Atlantic that have been handing off huge swaths of bone-dry air to the northern side of tropical waves. This is a pretty atypical pattern for the North Atlantic jet stream, but an effective one in suppressing convection, the building blocks from which storms form. It also looks to hold on a bit longer into early September.

So, is our culprit El Nino in the western Atlantic with shear? Or anticyclonic wave-breaking in the Main Development Region with dry air? The true answer is many factors are likely playing a role, to extents that will take post-season research to untangle. But in general, making a hurricane is like baking: you need flour, sugar, milk, and eggs, plus a heat source to make a cake, and tropical storms need low- and mid-level moisture, favorable upper-level winds, outflow, and warm oceans. For the last few weeks, the Atlantic has been missing its wet ingredients. The result is not atmospheric layer cakes, but dry piles of fail heated to five hundred degrees in the Caribbean Seas.

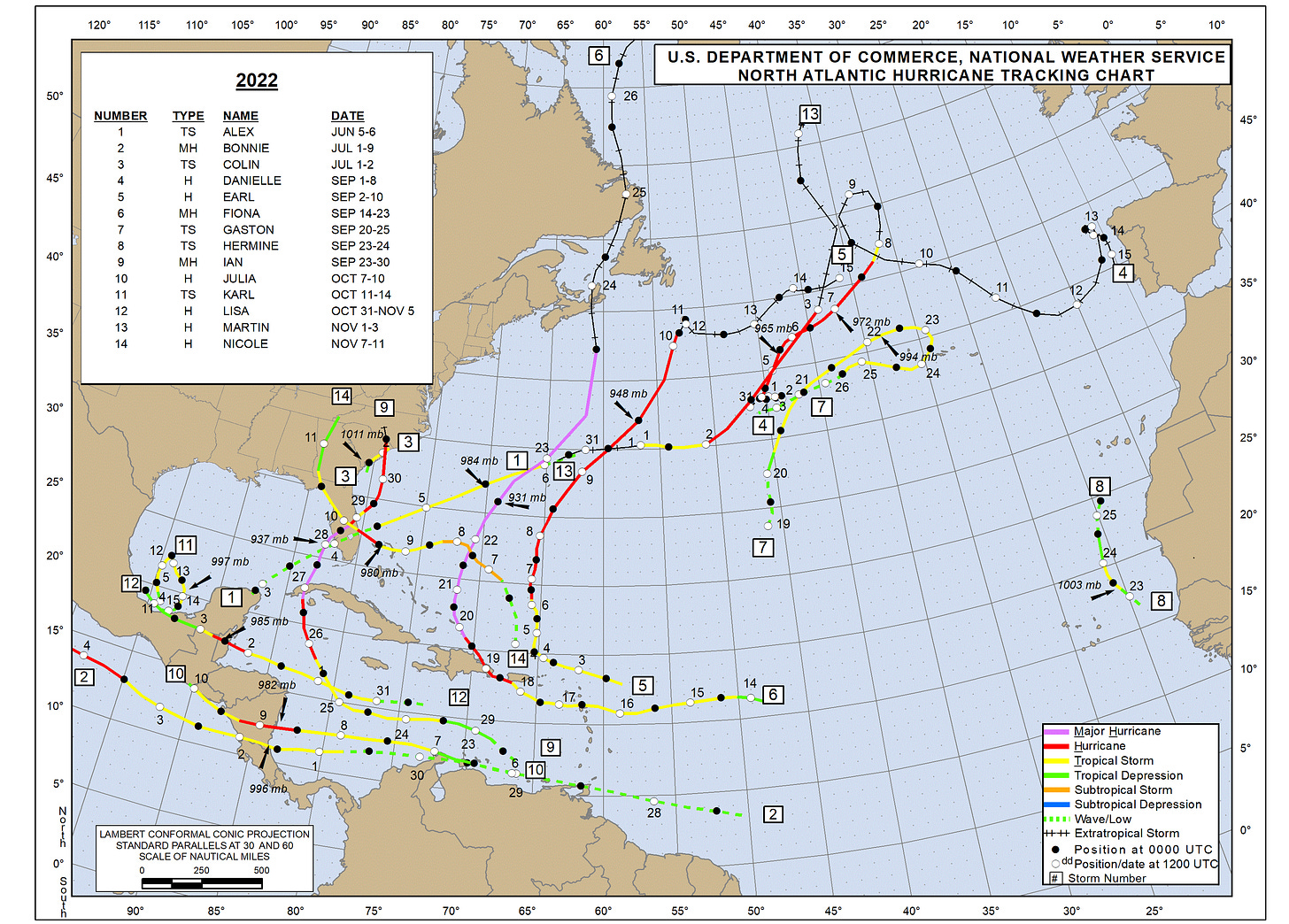

As we head into the peak month of hurricane season, those fast-changing weather factors can pivot on a dime. August 2024 has a number of pattern similarities to August 2022, a month in which above-normal activity was expected and zero named storms developed. September 2022 then brought six storms, including Ian, and ocean heat content is much higher entering September 2024 than two years ago.

In fact, the winds of change may already be kicking up. The National Hurricane Center is tracking a tropical wave in the central Tropical Atlantic that may escape dry air purgatory in the next week, and has some potential to get into the Caribbean and strengthen down the road. It’s not a sure thing by any means, but uncertain steering currents late next week might make this disturbance one to watch in for U.S. interests if it can indeed develop. Models are a little more supportive of eventual organization than a few days ago, so stay tuned. Disorganized thunderstorm activity will also keep the western Gulf Coast very wet over the next 7 days, and additional tropical waves may try to slowly organize in early September.

Could the Atlantic defy the odds and stay quiet in September? It’s possible, but I doubt it. If so, we should be thankful for the rare win. Maybe I’ll do the Will Shortz crosswords that have been sitting on my nightstand for 8 years, or learn to play the banjo instead of just owning a banjo. But keep in mind the climatological frequency of hurricane and major hurricane landfalls in Florida is essentially constant between late August and late October. Around 75% of Florida’s historical storm activity is still ahead, and only a fool would place a bet on the winds blowing fair for all of it. Keep watching the skies, though I won’t blame you for taking off Labor Day 2024.

Love the jab at amusements in the state parks ;)

As a 60-year guitar owner, including finally getting a Martin. A sometimes but not often player. Good luck with the Banjo, don't give up it only takes practice, more practice then after that more practice.