May Bees Don't Fly in September: Hurricane Watch Column for Sept. 5th

There are plenty of areas to watch in the Tropics, but no serious threats as 2024 splits from September hurricane history.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, plus coverage of every U.S. hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions.

Hurricane Season 2024 has fallen. Can it get up?

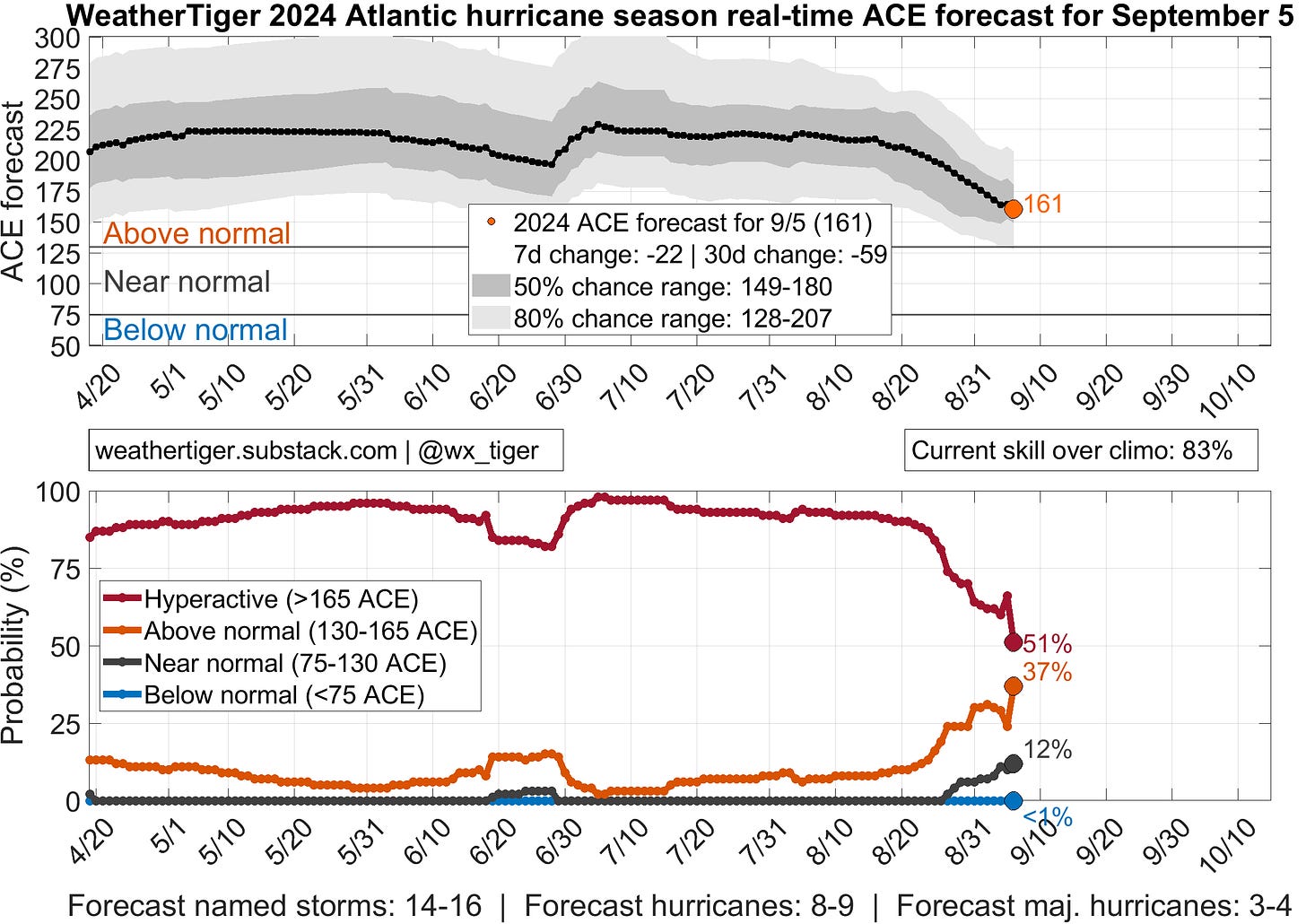

The second week of September is the climatological peak of Atlantic hurricane season. Accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), a measure of the cumulative strength and longevity of storm activity, hits the historical 50% mark about September 12th, as does Florida’s landfall activity. The continental U.S. reaches the halfway point for landfalls a little earlier, around the 5th, due to impacts tailing off more quickly in the western Gulf and New England than they do in Florida.

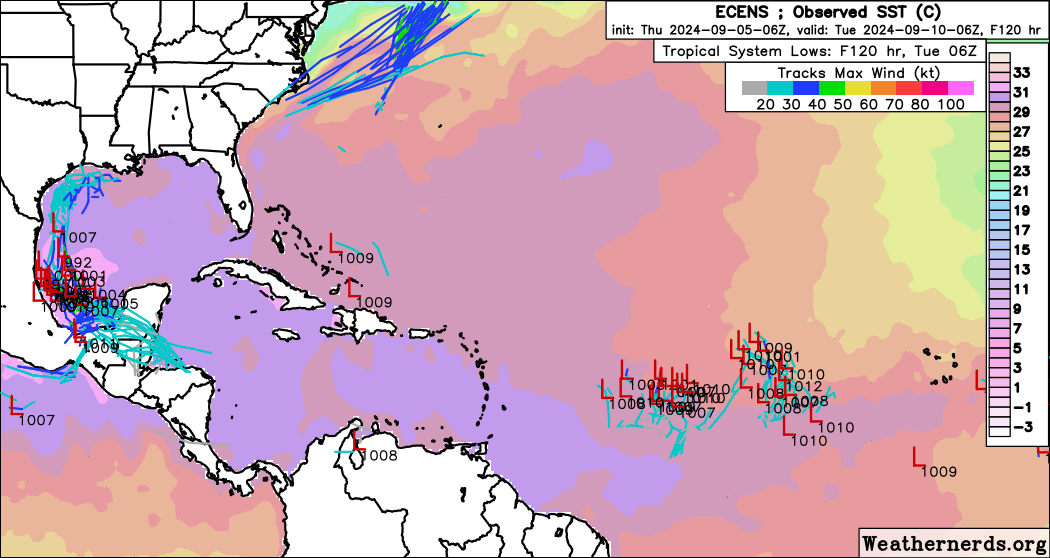

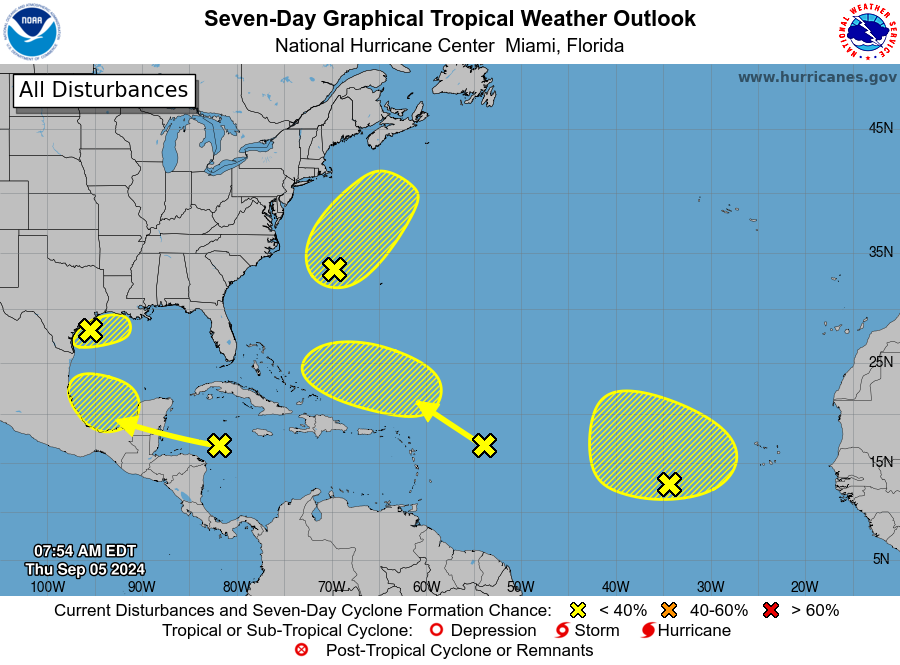

This year, the view from the mountaintop is strangely desolate. With no named storms forming in almost four weeks, the Tropical Atlantic looked so abandoned in late August that a Spirit Halloween superstore almost moved in. Today, there are a passel of areas of modest interest in the Tropics, but nothing suggestive of a major hurricane threat to the U.S. in the works. In fact, there is a clown car of five disturbances in the NHC’s Tropical Weather Outlook as of Thursday morning, though none with higher than a 30% chance of eventual development in the next week.

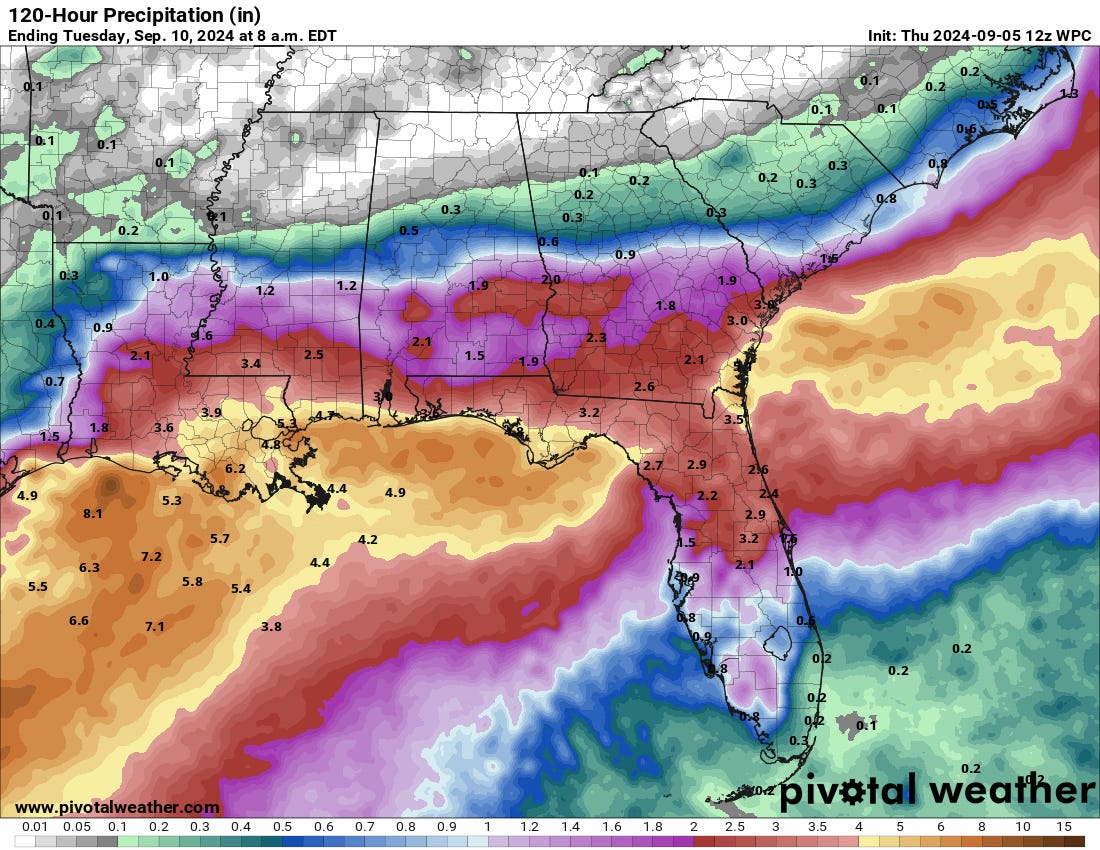

Only two of these features are relevant to U.S. coastal interests. The first is a knot of convection in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico southeast of Houston, which has been spreading heavy rainfall to coastal Texas and Louisiana since late last week. This weak area of low pressure is tangled up in a stalled front draped along the Gulf Coast, and its moisture will spread east over the next few days, increasing rain chances in Florida.

Development of a depression or weak named storm over the upcoming couple of days is plausible—this is September and the Gulf after all—but nearby shear should keep the system disorganized and prevent it from being something other than a rainmaker for the Gulf Coast. Look for 2-6” of precipitation from coastal Texas into northern and central Florida over the next five days either way.

That unfavorable environment will probably split that disturbance in two in a few days, with one piece heading east and one south. The southern piece may merge early next week over the far southern Gulf with a tropical wave currently in the western Caribbean, then mill about for a while. There is potential for this combined system to drift back north at some point next week, though strong upper-level winds expected across the northern Gulf should prevent anything other than another sloppy rainmaker from occurring. Still, in September 2024, this is thankfully what passes for something to watch in the Tropics at long range.

The other three systems are inconsequential. A frontal low several hundred miles east of the Outer Banks may briefly take on subtropical characteristics and steal a name before being swept northeast and out-to-sea over the weekend, and a pair of tropical waves in the eastern Atlantic’s Main “Development” Region will fight a losing battle against shear and dry air into next week. The westernmost wave has some chance of development east of Florida in the middle of next week.

So, we’ve got a lot of maybes on the map, but to quote Laura Ingalls Wilder, “May bees don’t fly in September.” This is the time of year when major hurricanes are common in the Tropical Atlantic, and the fact there are none today and no realistic expectation of one in the next week or more takes a huge bite out of the odds of a hyperactive hurricane season. WeatherTiger’s real-time seasonal model has plunged over 60 ACE units in the last month, and that steep decline will continue without powerful and persistent storms developing in the second half of September. (Check back each day for updated predictions here, including to see how U.S. landfall odds are shifting.)

Will they? Well, there’s no strong evidence to support that right now. There are, however, indications that the surprisingly hostile environment suppressing storm development in the Tropical Atlantic for the past several weeks will become less unfavorable in about 10 days. As I discussed last week, the hold-up is probably due to the overlap of tropical waves coming off of Africa unprecedentedly far north, while an unusual and persistent weather pattern in the eastern Atlantic drives dry air south into the path of those waves. That’s not a pattern we’ve really seen before in the Tropics over an extended period of time during peak season, which is why none of the seasonal models, including ours, anticipated it.

However, waves shift south in late September as the African monsoon weakens, and models are indicating that the dry air intrusions may tail off as well beyond the 15th. That could indicate better chances of a strong hurricane or two in late September, which would be historically typical. Alternatively, it could mean Atlantic tropical activity finds another new, innovative way to fail in 2024. In terms of risk, delaying development is excellent, as the chances of tropical waves making it all the way across the Atlantic and threatening the U.S. decline as the month goes on. There are plenty of historical major hurricanes in late September. Not all, but most curve north into the open Atlantic.

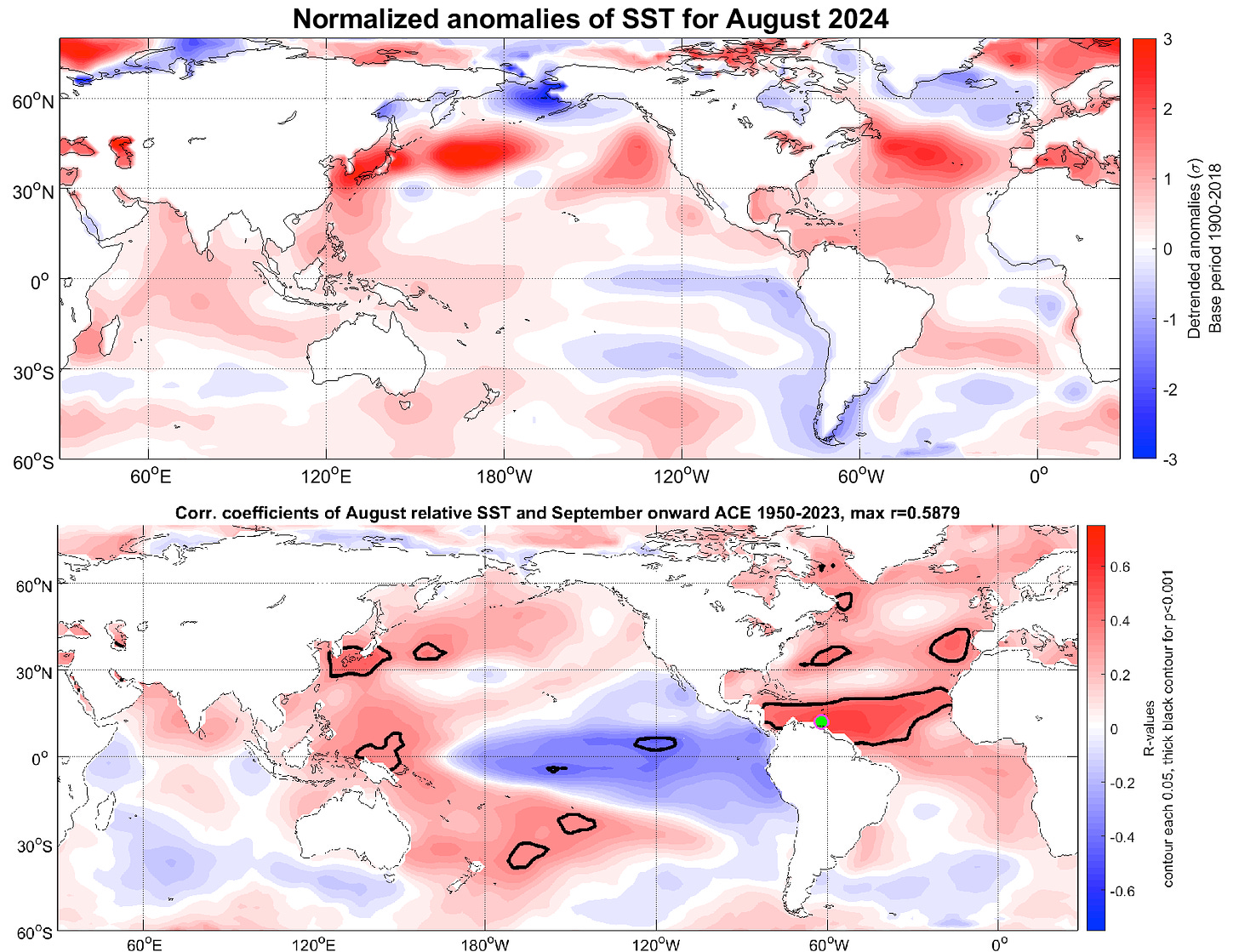

That said, there’s still a long time to go. The rules of what makes for an active hurricane season may have been abruptly swapped out in 2024 like Apple products changing their charging cables, but the strongest historical predictor, ocean temperatures, continues to signal that the hurricane season will more than likely flip to being active at some point. In the meantime, enjoy the unusually clear view from the peak and keep watching the skies.