Five Years' Time: A Hurricane Michael Retrospective

Five lessons from Category 5 Hurricane Michael, five years later.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

At 12:30 p.m. Central Daylight Time on October 10, 2018, the inconceivable happened in North Florida: a Category 5 hurricane landfall.

Michael was one of the strongest handful of hurricanes ever to strike the continental U.S., just the fourth Category 5 on record, and the first Category 4 or higher landfall ever in Florida north of a line from West Palm Beach to Charlotte Harbor. The five years since Michael’s 160 mph winds and 14’ storm surge seemingly rended the fabric of space and time have brought slow healing to the ravaged towns of the Forgotten Coast and Apalachicola River Valley. Thankfully, the worst-affected areas have had the opportunity to recover without another hurricane landfall since 2018.

Yet a cataclysm like Michael is never really over, echoing for decades to come in the altered lives, scarred land, and twisted billboards of the Central Panhandle, and in the ways it permanently transformed how hurricanes are prepared for and predicted. As we look back across the five-year gulf of time separating us from this Category 5 monster, five key lessons and changes spurred by Michael come to mind.

Watch the NHC, not models

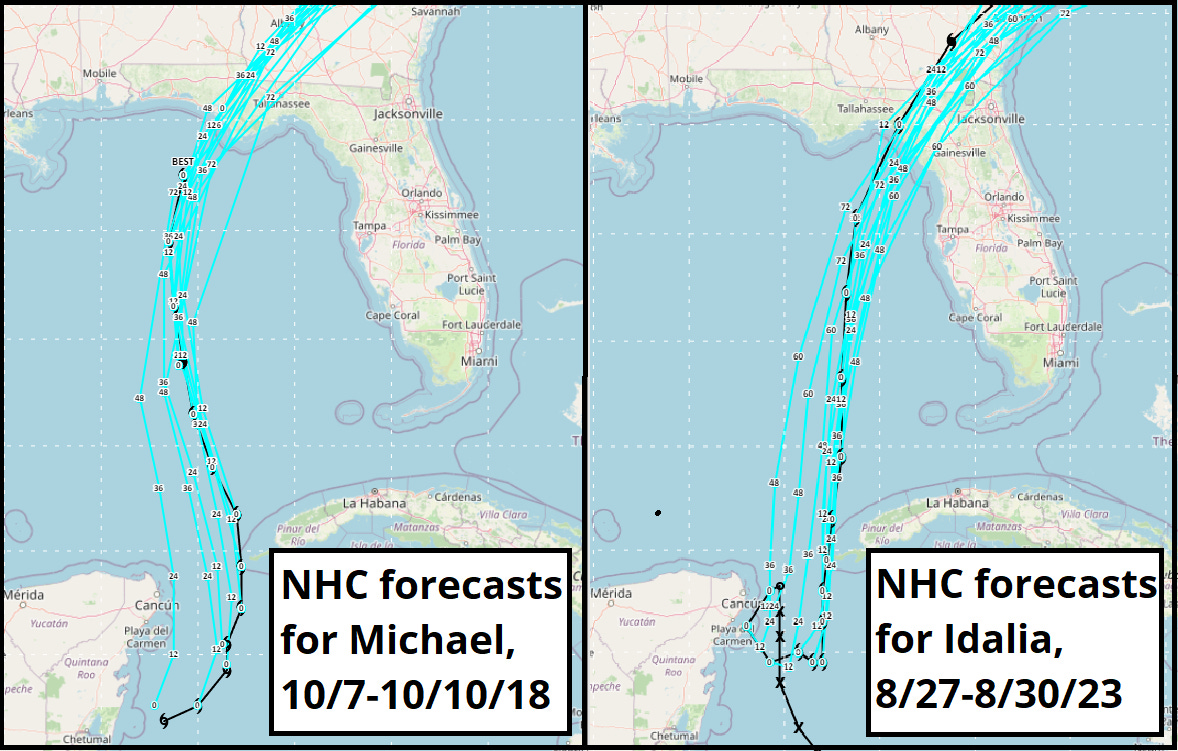

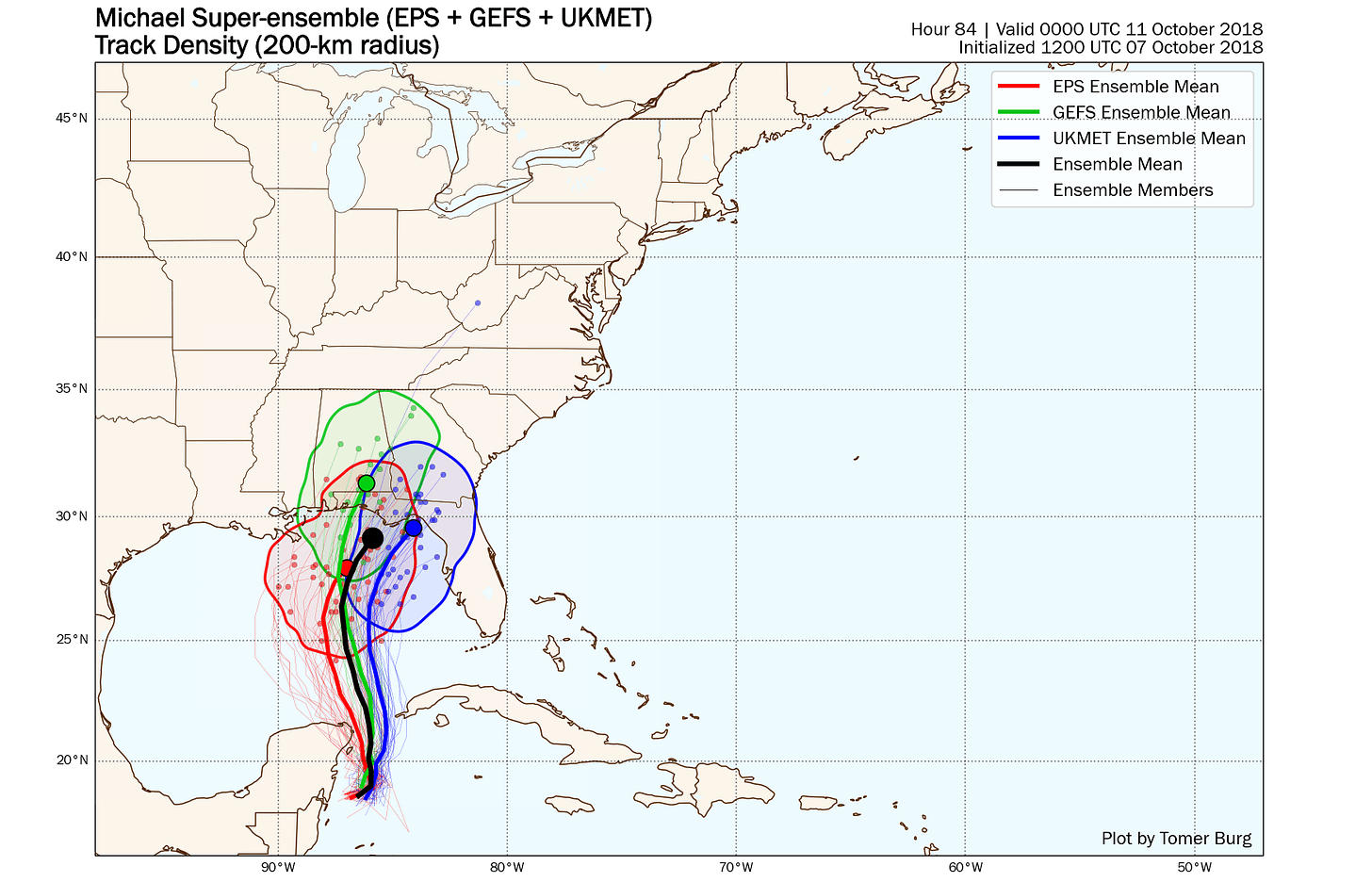

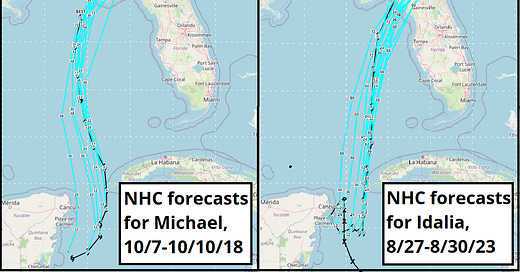

Consistency is a hallmark of National Hurricane Center track forecasts, not individual hurricane models. Despite a wide spread in model guidance, once Michael became a tropical storm on the morning of October 7, the NHC never wavered in predicting eventual landfall in either Bay, Gulf, or Franklin County. (Michael’s precise landfall point was Tyndall Air Force Base in eastern Bay County, about 10 miles west of Mexico Beach.) More recently, each NHC track forecast for Idalia predicted a landfall location in Levy, Dixie, or, correctly, in Taylor County.

Point being, in any storm there could be an individual model with a slight edge on the NHC’s forecast accuracy, but there is little consistency in which model that is from storm to storm. As they did in Michael and Idalia, the human experts at the NHC leverage real-world observations and their knowledge of the models’ idiosyncrasies to produce an optimized, stable forecast. Obsessing over the six-hourly vagaries of the 12z Canadian, 06z ICON, or 17z Magnavox model is far more likely to give you ammunition to confirm your bias—whether that bias is to overreact or underreact to hurricane threats—than to aid decision-making and preparation when time is most of the essence.

Life comes at you fast

While Michael developed in a common region for October hurricane formation, it differentiated itself from the masses of late-season Caribbean storms by intensifying from the moment it developed until landfall. Between October 7 and 10, Michael’s maximum sustained winds failed only once to increase by at least five miles per hour each six hours, leaping over 120 mph in total over three days.

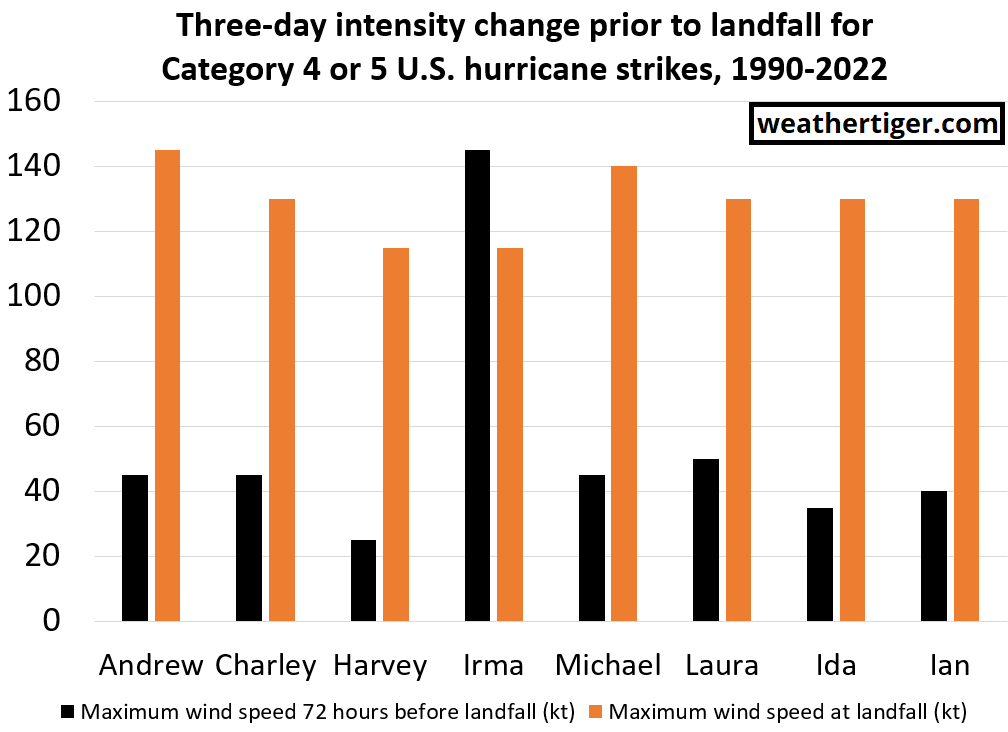

While rare overall, extreme intensification in the run-up to landfall is a shared trait of the most destructive hurricanes. Of the eight Category 4 or 5 hurricanes to have struck the continental U.S. since 1990, seven were tropical depressions or tropical storms three days before landfall. Andrew, Charley, Harvey, Michael, Laura, Ida, and Ian all saw sustained winds increase by at least 90 mph in the 72 hours before reaching the U.S. coast, while only Irma did not.

Limited lead time is the norm for catastrophic hurricanes. The reality of living on or near the coast is that you need to be nimble and able to react at short notice to protect life and property.

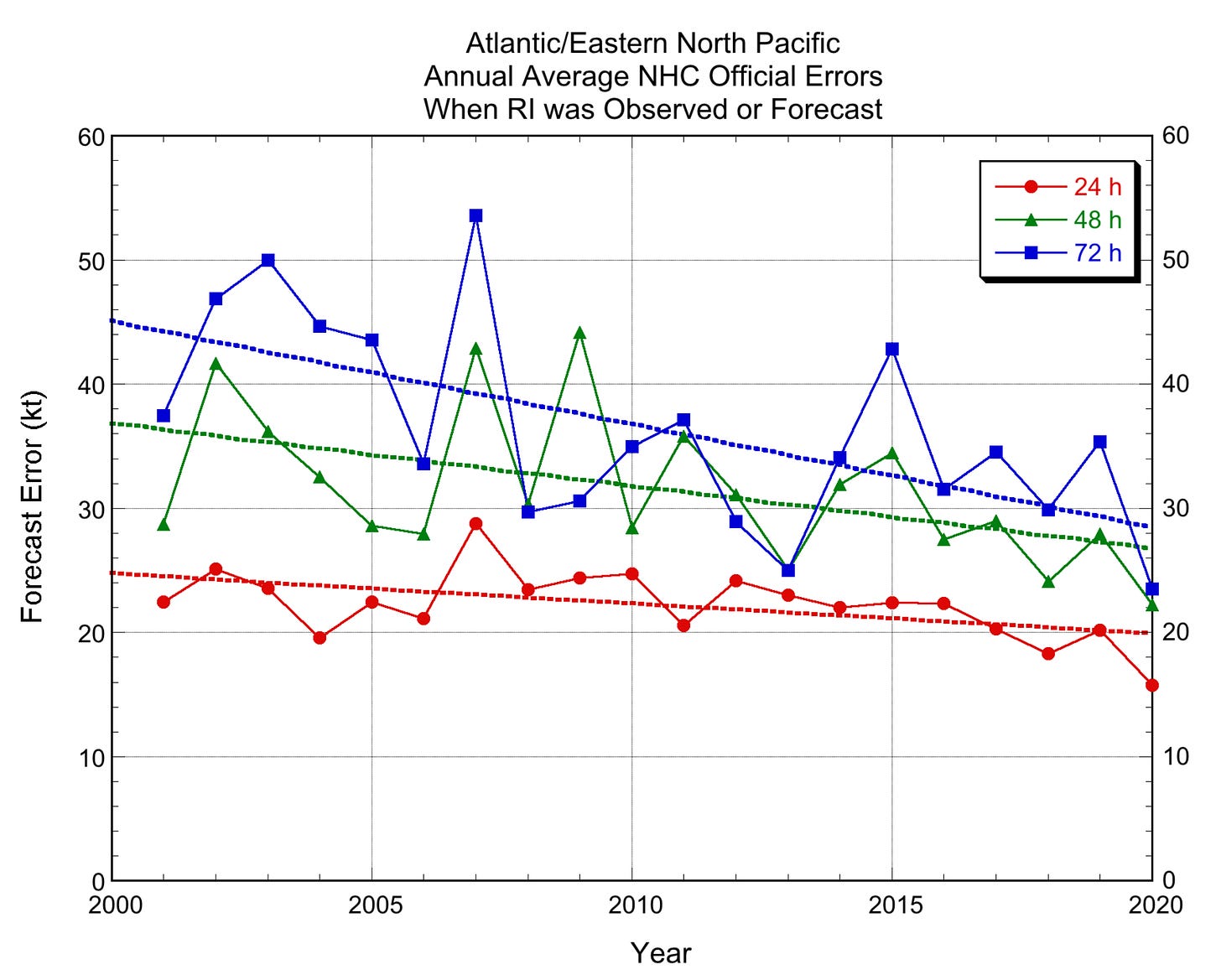

Rapid intensification forecasts are improving

The good news is that Michael itself has contributed to extending that lead time a bit. NOAA research flights and Air Force Hurricane Hunters gathered extensive data from Michael as it strengthened, and that data was used to better understand the mystery of hurricanes’ inner cores and develop the next generation of track and intensity models, like the now-operational HAFS model suite.

The wild beast that is rapid intensification hasn’t been fully domesticated in the last five years, but there have been gains. Sixty hours prior to Michael’s landfall, the NHC intensity forecast had it peaking as a Category 2; sixty hours prior to Idalia’s landfall, the NHC accurately projected that a peak of at least Category 3 intensity was “increasingly likely.” Rapid intensification will always be challenging to predict, but thanks to hard work from hundreds of aviators, researchers, and forecasters, a tragedy like Michael contributes to mitigating future tragedies.

The future is not like the past

Unfortunately, meteorologists need to continually up our game, because hurricane seasons are throwing curveball after curveball. As I said immediately after Michael, what happened was so far beyond hurricane history’s worst-case scenario for North Florida that I had trouble accepting Michael actually happened. In 2023, with 5 more years of sustained weirdness under our belts, most people are further down the path of accepting that hurricane seasons of the future will not be constrained by history.

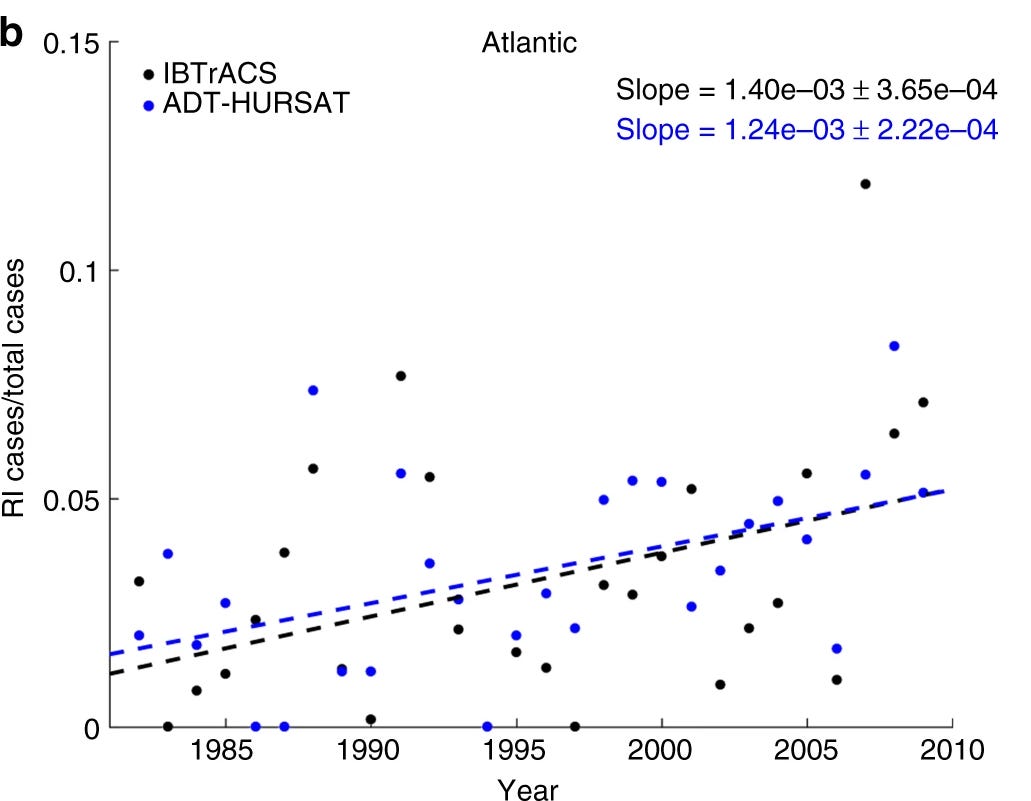

While scientists aren’t sure whether there will be (or already are) changes in how favorable the atmospheric environment or steering currents are for producing landfalls, there is ample observational evidence and a strong physical argument that Michael-like rapid intensification events are more common now than even a few decades ago as oceanic heat content rises. Several studies suggest that the net severity of hurricane landfalls may continue to trend higher, particularly on the Gulf Coast, even as there may or may not be more landfalls overall.

Thank a fire ranger

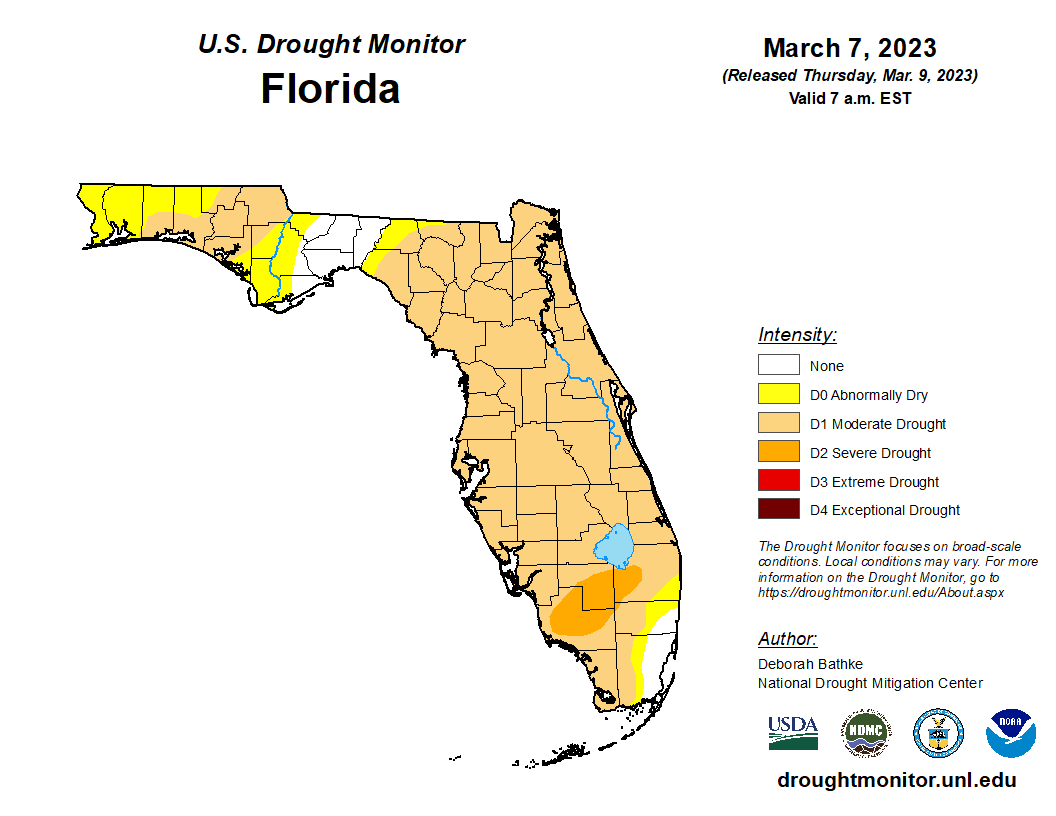

Michael blazed a trail across a heavily wooded part of Florida and Georgia, felling an estimated 70 million tons of timber. Despite this treepocalypse and three intervening years of drought-inducing La Ninas in the intervening time, North Florida has seen some wildfires but largely escaped the kind of residential-area conflagrations seen elsewhere in the last few years.

Why? Well, thank the Florida Forest Service. Florida is one of the most aggressive states in permitting and performing prescribed burns that reduce the fuel available to wildfires and support the health of fire-dependent ecosystems. It’s easy to not think about disasters that don’t happen, but creating fire lines around populated areas and proactive management of the Panhandle’s flattened forests post-Michael may well have prevented another crisis.

Looking out at the Atlantic this week, there’s no indication of another Michael in the making. Eastern Pacific moisture will overspread the Florida Gulf Coast this week, but any serious U.S. threats this season are unlikely until at least the second half of October. The waters of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea are calm, if unnaturally warm. In the Panhandle, Michael has receded to an unpleasant memory for most, still a daily reality for some.

I don’t know if North Florida will ever see another hurricane as extreme as Michael in our lifetimes, but someone will. Given the probable return period of a Category 5 to the eastern Gulf Coast, it might happen in three weeks or 300 years. As we wait, all we can do is internalize whatever scientific and societal lessons can be gleaned from this horrific storm.

And, perhaps, we are learning. Five years after Michael, Hurricane Idalia’s wind and surge thankfully caused no direct deaths on the Florida Gulf Coast. In five years’ time, who knows how much more hurricane forecasting and risk mitigation may improve: hopefully, not via repetition. Keep watching the skies.

I really enjoy your all of your articles and appreciation your knowledge and devotion. Thx for making our lives a little safer every day. Mark Hoffman

Excellent discussion and proof that following a few individual models is a form of ‘wishcasting’ that only adds hype to those commercial interests that feed off it. The men and women of the NHS are always the best and most reliable experts to follow. Thanks for this post!