Stump the Tiger, Ian Edition: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for October 26th

Answering Ian-related reader mail and cone quandaries, and watching for possible development in the Caribbean heading into next week.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused tropical briefings each weekday, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

As an unseasonable chill settles on our Home Depot 12-foot Lawn Cthulhus, the days of hurricane season dwindle down to a precious few. This week marks the anniversaries of the 1921 Tampa Bay Hurricane and 2020’s Zeta, the final historical major hurricane landfalls on the calendar; in the past 172 years, only 13 tropical storm and 7 hurricane landfalls have occurred in the continental U.S. on or after October 27. Overall, less than 3% of net U.S. tropical impacts are still ahead.

Hurricane season isn’t over, but to quote the Beatles, it’s getting very near the end. Unfortunately, activity tends to drag out in La Nina years, and 2022 is no exception. While there’s nothing rapping at our chamber door this spooky season (side note: Poe underestimates wind as an adversary), there are a couple of disturbances worth monitoring in the upcoming week.

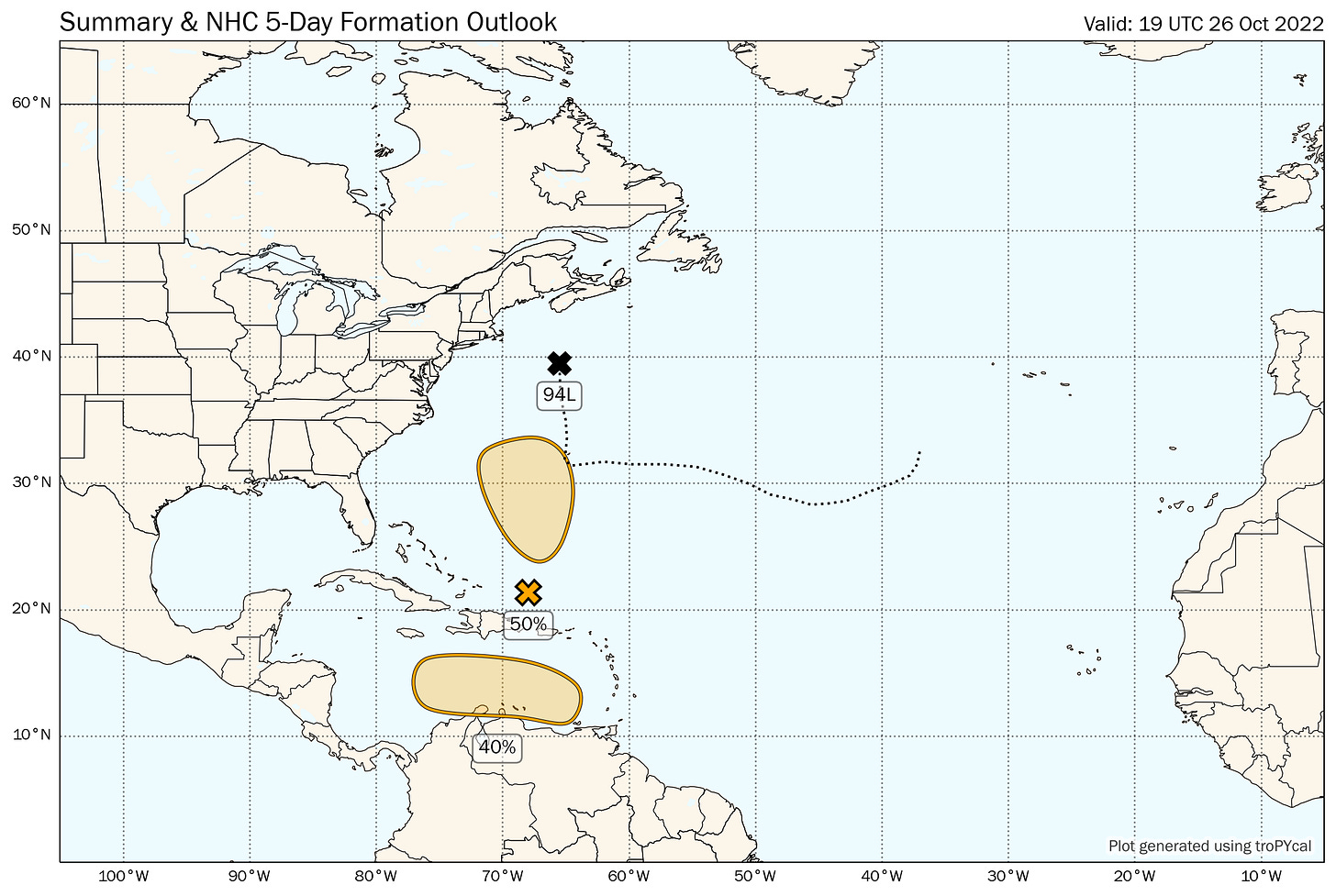

The more innocuous of these is a trough of low pressure southwest of Bermuda, along which a subtropical depression or storm may spin up in the next few days. While short-lived development is possible, this system is not a threat to the U.S., and conditions will turn more hostile early next week. Anything forming here is likely to be swept out to sea while weakening or dissipating in 5 to 7 days.

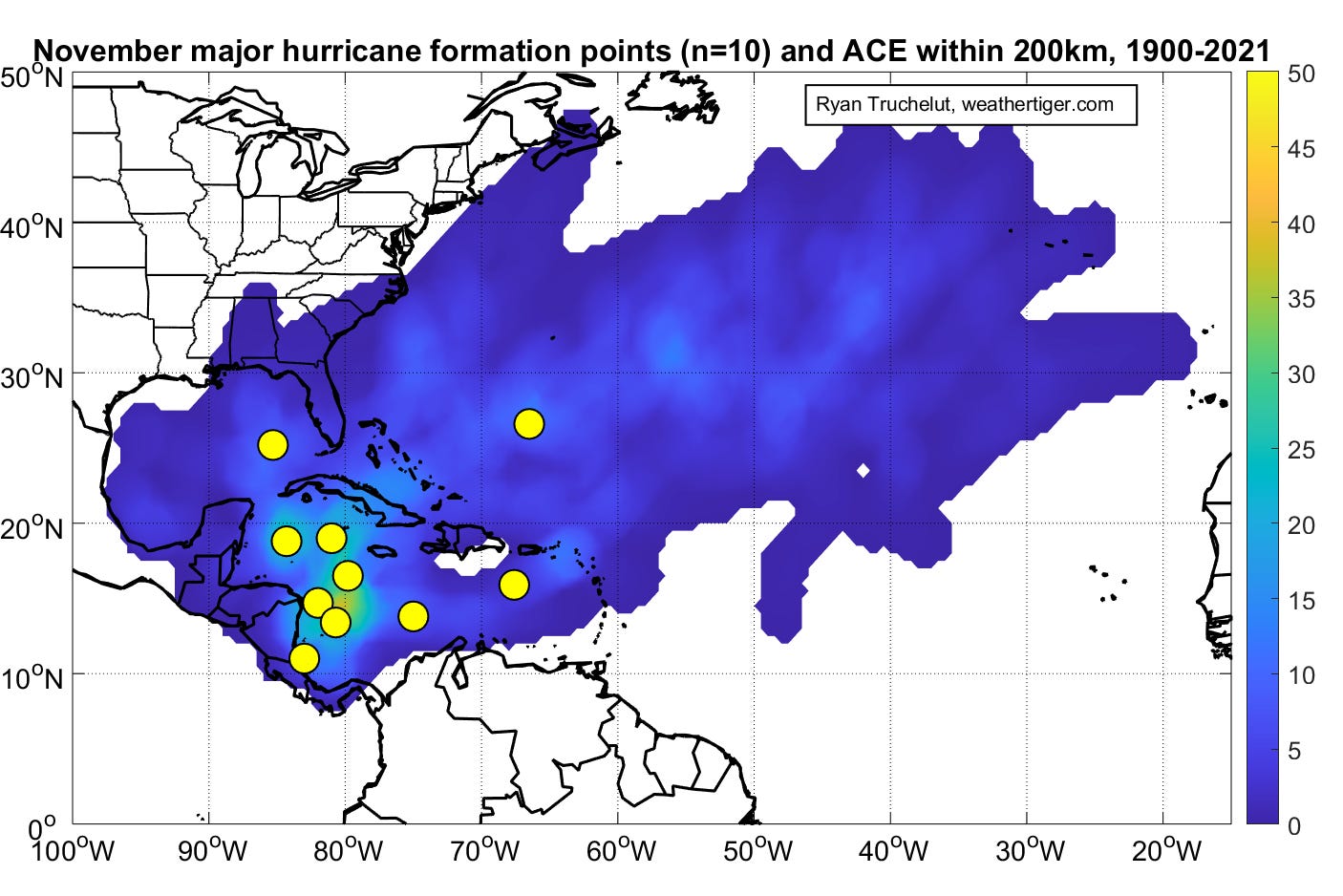

Slightly more concerning is a tropical wave in the eastern Caribbean Sea bringing heavy rain to Puerto Rico and the eastern Antilles today. Shear is expected to diminish, and the outflow environment improve as this wave tracks over the warm and deep waters south of Hispaniola and Cuba, so there is realistic potential for development in 3 to 7 days. Eight of November’s ten Category 3+ storms since 1900 have developed in the Caribbean, so climatology indicates there is plausible intensity upside if the circulation can consolidate and stack quickly.

Models support eventual development of this system, with most favoring a westward track towards Central America. The good news is high pressure positioned over the Southeastern U.S. next week makes a turn north into the Gulf unlikely. However, November tropical activity is known for bizarre tracks, like Hurricane Eta’s eta-shaped path in 2020, so I’ll keep an eye on it in case the western Caribbean steering environment swerves again.

With this wave probably someone else’s problem, WeatherTiger is powering down for a long winter’s catnap in a beam of sunlight near a heating vent, and this will be the final scheduled column of 2022. In celebration of my very particular set of skills (hopefully) no longer being required, I asked last week for your questions about Hurricane Ian. You all responded with a plethora of thoughtful quandaries, insightful and/or zany ideas for cone reform, and genuine concern for the physiological and environmental consequences of excessive LaCroix consumption. To the mailbag!

Q: I have a question on when the NHC (or NOAA or whoever is responsible) makes the final determination of Ian’s category, wind speed and storm surge. I seem to recall that Michael was posthumously declared a Cat 5 several months later, after damage and data was analyzed. -Missy, Fort Myers Beach

A: Hi Missy, you are correct that Michael’s maximum sustained winds at landfall were revised from the real-time estimate of 155 mph up to 160 mph, or Category 5 strength, in post-analysis. After the hurricane season ends, NHC scientists gather all available data for each storm from satellite, aircraft, radar, weather stations, and other sources, including information unavailable while forecasting.

Without the time pressure of predicting an active storm, they carefully and thoroughly consider the evidence and make a final determination of the position and intensity of the storm each six hours over its lifespan. Minor changes to the operational advisory track and strength are common. This data is then released in a comprehensive Tropical Cyclone Report for each storm.

Not surprisingly, Hurricane Ian’s report will be complex and lengthy, so look for a probable release timeframe between March and May of next year.

Q: Not sure if you have commented on the eyewall collapse and reconstruction in Ian just before landfall that caused additional surge and damage. Would like your take on this. -Scott, Panama City Beach

A: Hi Scott (and others with similar questions), Ian’s structural changes in the 24 hours leading up to landfall absolutely heightened its destructive prowess. On the evening of September 27th, Ian underwent what is known as an eyewall replacement cycle (ERC). In this process, the intense, circular inner eyewall of a mature hurricane weakens and is replaced by a larger outer eyewall. An ERC typically results in the hurricane’s maximum sustained winds temporarily decreasing, but the idea that net weakening occurs is pure pyrite. Most of the time, ERCs increase the storm’s total wind energy by expanding hurricane-force and tropical-storm-force wind radii.

In Ian’s case, the unusually expeditious contraction of the new eyewall early on the 28th meant the hurricane brought the worst of both worlds into landfall, packing a broad outer windfield that drove a massive surge and a tight inner core of destructive Category 3 and 4 sustained winds.

[All manner of cone-related opining] -Everyone, Everywhere

Cone thoughts: you’ve got them, Florida. The tenor of many responses I received to last week’s column was a) shock that the cone means what it actually means and b) a sense that the cone did not convey the myriad threats posed by Ian. As with everything else in the world these days, there is consensus that change is necessary, but little agreement on what form that change should take.

Currently, the NHC is conducting surveys to gather data on how Ian forecasts were perceived by those in harm’s way, and how those perceptions led to action or inaction. The results of these studies will inform revisions to NHC products, and may usher in a new generation of frontline forecast graphics optimized to communicate the core surge, wind, and rain hazards where people are finding their information. If Google spends millions performing A/B testing as to whether 12-point Ariel Extra Bold or 11.5-point Helvetica Neue gets one more person to click on “language professors HATE this man” banner ads, we need to have a similarly rigorous process for polishing the format of life-saving storm information.

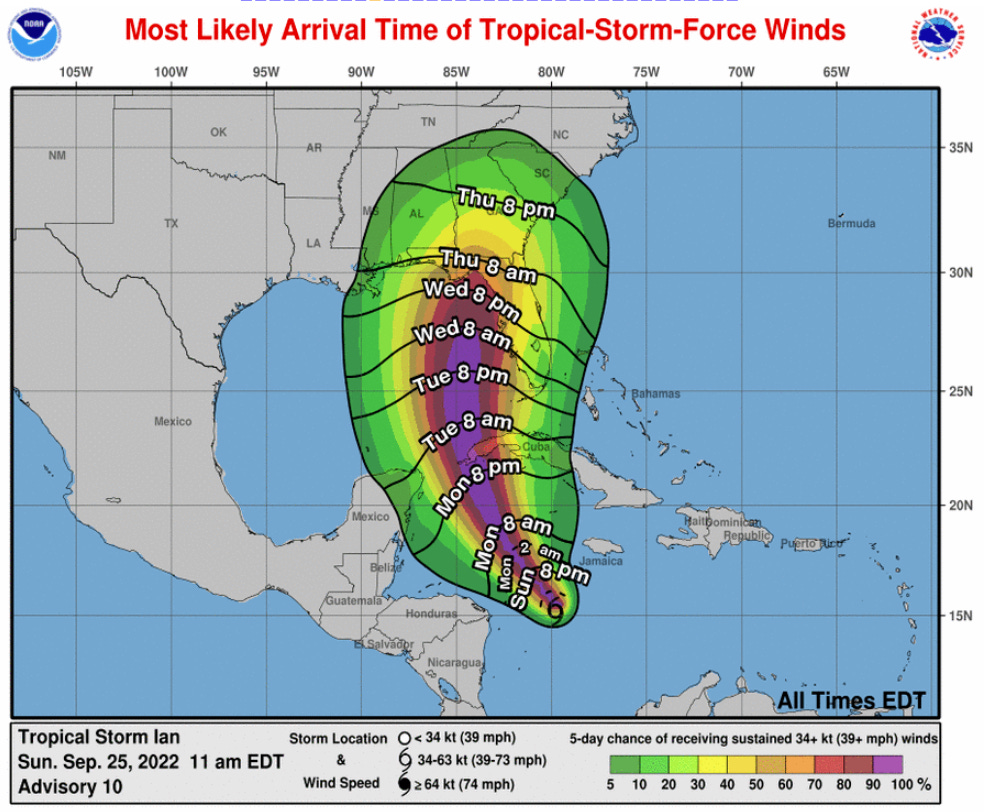

Personally, I think that the cone could be supplanted by a modified version of the existing probabilistic wind forecast, perhaps one also showing Storm Surge Watches and Warnings for the coast. Doing so would further prioritize the human impacts over the esoteric concept of center location, and would factor in both track uncertainty and storm size. Crucially, the storm size forecast is something over which forecasters have control, unlike the dimensions of the cone, which would permit better alignment of NHC key messaging and graphics. I’m not pretending to have all the answers here and defer to the results of the survey, but don’t be surprised if some revisions in the NHC’s graphical forecast products are made prior to 2023 season.

Thanks again for the feedback (if I didn’t get to your question today, look for an email soon), and as always, I appreciate your trust and readership over this challenging year. Free subscribers, look for WeatherTiger’s traditional hurricane season wrap-up at the end of November; paid subscribers, your bulletins will continue until the season is done, particularly while storms or rumors of storms continue. Until then, keep watching the skies.

You are the bomb!!! And also witty!