Initial Descent: WeatherTiger's Weekly Column for October 14th

The Atlantic remains quiet, but there are hints of possible Caribbean development next week.

WeatherTiger’s weekly column is provided free to all subscribers. For more insights, upgrade to premium for as little as $7.99 to get daily forecast briefings, in-depth forecasts, videos, and live landfall coverage during U.S. hurricane risks, expanded seasonal outlooks, and the ability to comment and ask questions. Click below to sign up below now.

Two-sentence threat synopsis: There are no U.S. threats currently in the Tropics. Chances of development in 6-10 days or more in the western Caribbean are rising slightly, but there remains no indication of any risk to Florida or the U.S. at this time.

In a rare concession to decency uncharacteristic of the last few hurricane seasons or the 21st Century generally, the news regarding the Tropics remains cautiously optimistic as the second half of October dawns.

The only current Atlantic, Caribbean, or Gulf disturbance with even a slight chance of development is a sheared area of low pressure north of Hispaniola. Upper-level winds will continue to be inconducive for organization as it slides east into open waters and merges with a front over the next few days.

Thus, there are no concerns in the short-term as another five days is likely to pass without tropical development. At the risk of incurring bad juju: is hurricane season over?

Certainly, we all hope so. Most normal people checked out of hurricane season a month ago. I’m obligated to not do that, but prefer my strict off-season regimen of reading Wikipedia articles about rollercoasters, bridge disasters, and aircraft carriers over forecasting any further threats.

And, true, late October and beyond is a time of diminishing returns in the Atlantic. Only about 10% of total tropical activity and 5% of continental U.S. landfall activity occur after October 20th, which shrink to around 5% and 2% after November 1st.

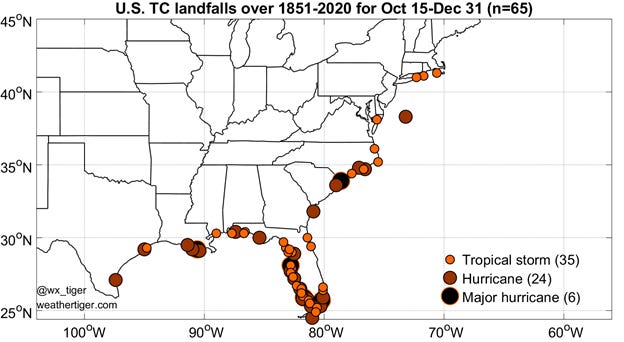

Late-season impacts are not all that uncommon, with a tropical storm or hurricane making landfall in the continental U.S. after October 15th in about 25% of seasons. However, many of those impacts happen in the third week of October, and about 10% of seasons have a U.S. landfall after October 25th. The most common location for these historical strikes is southwest Florida.

The rarity of U.S. landfalls in late October and November is due to the seasonal incursion of mid-latitude weather, which moves from west to east, into the Tropics. While the waters of the Gulf and Caribbean remain plenty warm for hurricane formation through fall, more frequent frontal passages cause average wind shear to skyrocket like an exurban Zestimate by the start of November, as well as flood the zone with dry continental airmasses.

Late October and November’s mid-latitude steering currents typically guide Caribbean storms more northeast across the Greater Antilles rather than north or northwest towards Florida. As with every tendency in tropical meteorology, there are exceptions like last November’s Eta, which made two Florida landfalls at tropical storm strength.

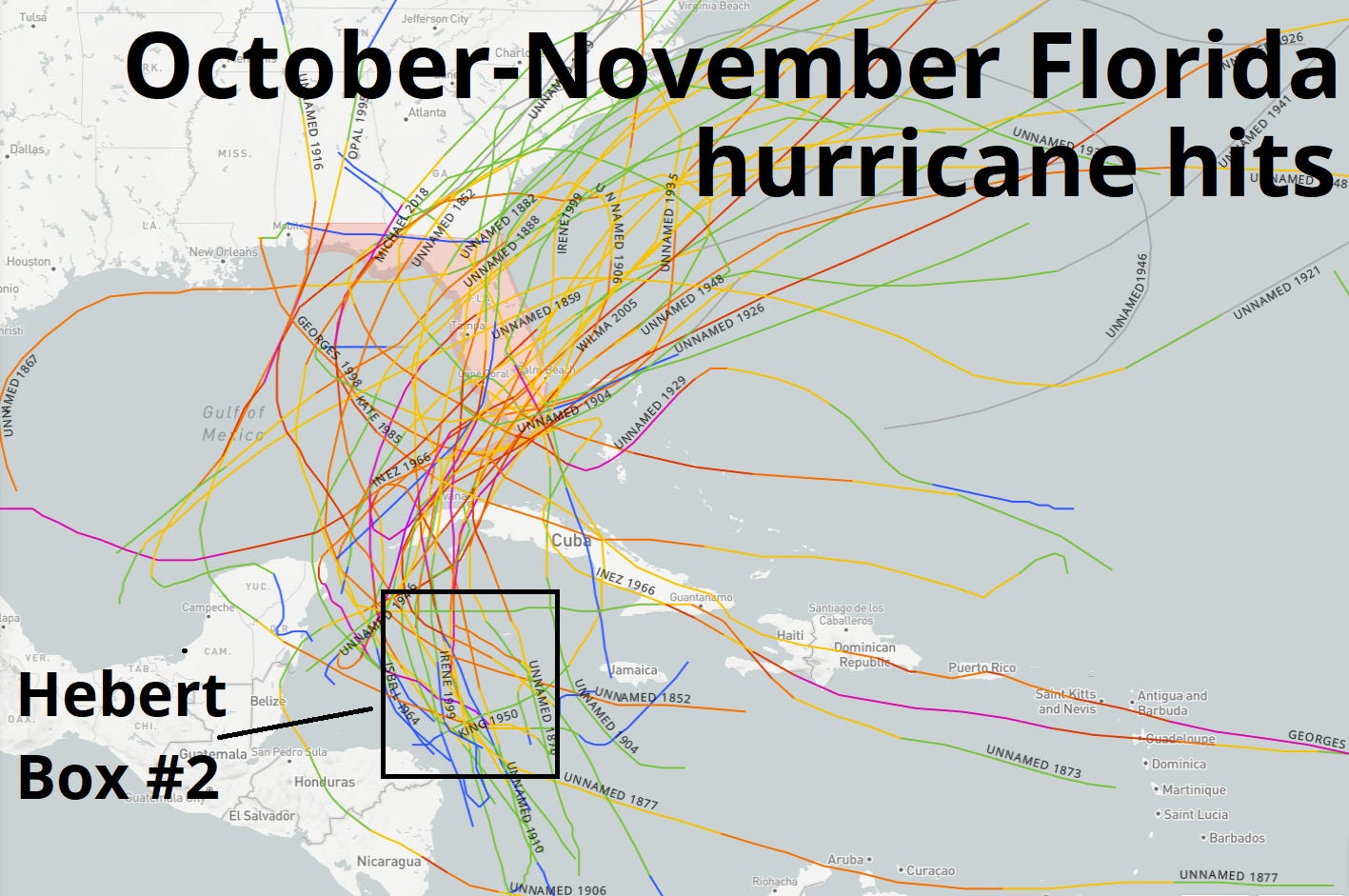

The 40 historical hurricanes that struck Florida in Octobers and Novembers since 1851 overwhelmingly share a point of origin, with 80% developing in the western Caribbean. Most of these passed through the region between Honduras and Cuba known as “Hebert Box #2” (pronounced ay-BEAR) after the former National Hurricane Center forecaster who identified this commonality.

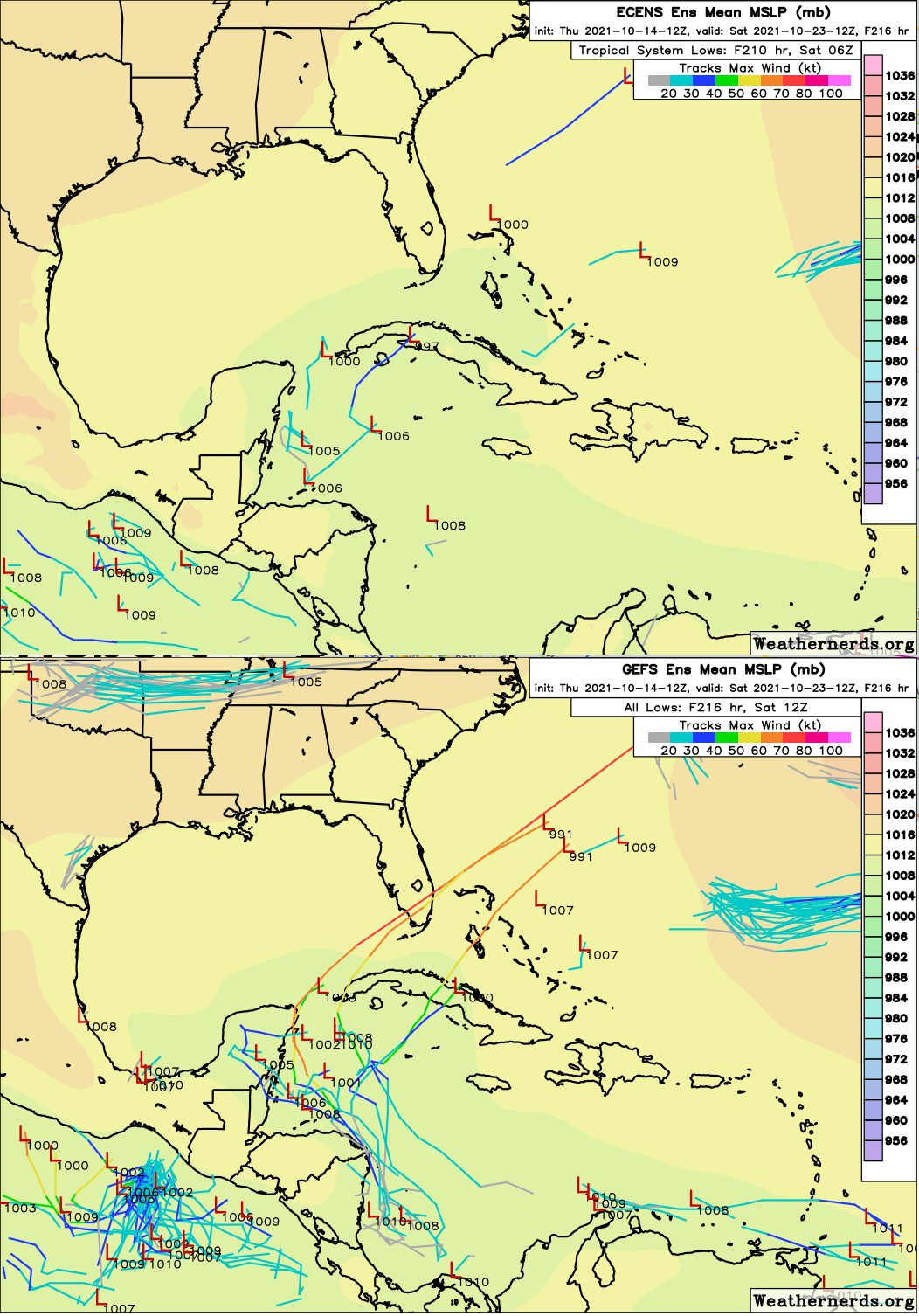

You might say that any disturbance in western Caribbean at this time of year (content warning: dad vibes) Hebert-s watching. Fortunately, the Caribbean is quiet today and expected to remain that way for another 5 days. There are some indications that upper-level winds will trend more supportive for tropical activity starting early next week, and a smattering of American and European ensemble members show a stalled front triggering development in the Caribbean in 6 to 10 days.

Even if something forms, persistent eastern U.S. troughing would probably keep any resulting storm from getting too far north. Still, this region is worth monitoring next week, as stalled fronts are a classic mechanism for October tropical development.

An old-school mnemonic proclaims that hurricane season is “all over” by October. That clearly isn’t true— hurricane season isn’t over until the first time you hear “All I Want for Christmas is You” over grocery store speakers. Still, escaping mid-October without a hurricane threat increases the chances of making it cleanly through the rest of the year. The western Caribbean may not be quite done, but hopefully we won’t need to keep watching the skies for much longer.