Hurricane Model Power Rankings 2022: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for July 20th

How do hurricane models stack up against each other as the peak of the season nears?

“What does it take to be number one?”, asks the poet-philosopher Nelly, who unfortunately goes against the Socratic method by subsequently observing, “Two is not a winner, and three nobody remembers.”

While I would argue the second part of this statement is an unnecessarily zero-sum approach to life and that most endeavors that matter are collaborative, it does peg the human obsession with ranking stuff whether it needs to be ranked or not. So, with the Tropical Atlantic in a mid-summer lull, it’s time for WeatherTiger & Associates’ 2022 Hurricane Model Power Rankings1.

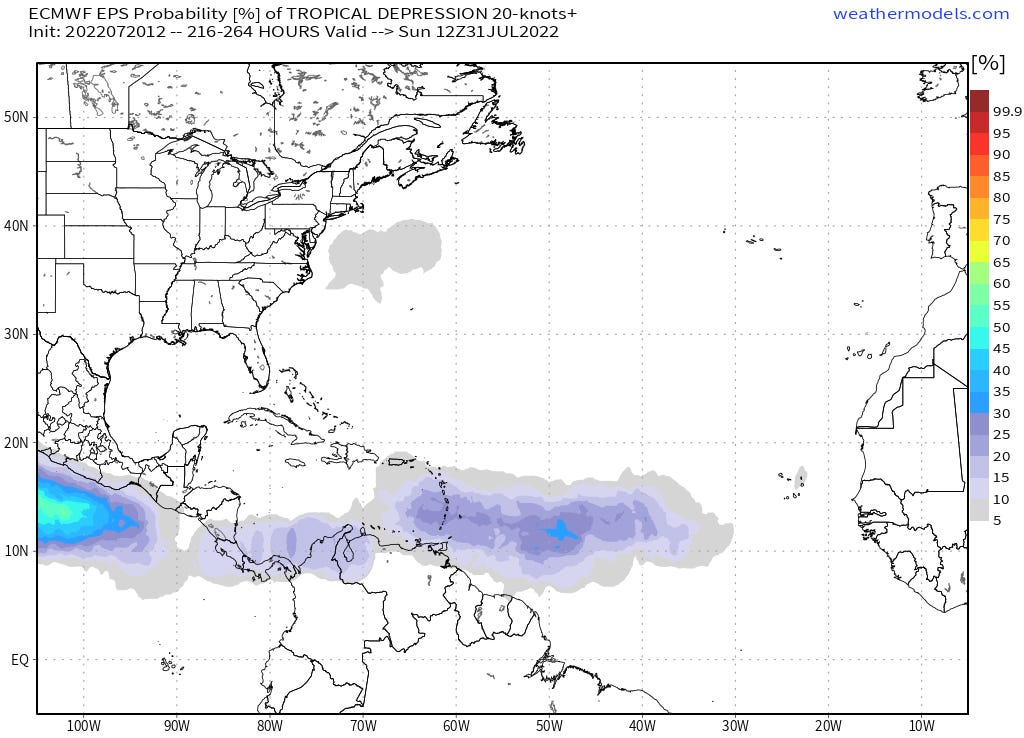

The good news is that the Atlantic is dusty, quiet, and likely to stay that way through the end of July. Conditions may start to become a little more conducive for tropical development towards the tail end of the month, at which point a tropical wave crossing the central Atlantic may be worth watching. But in the short and medium term, it’s smooth sailing in the Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean for another 7-10 days.

Meteorologists can make predictions like that with confidence thanks to computers’ incredible facility with repetitive math problems. In a nutshell, computer models use information about current weather conditions and the physics equations that describe how fluids behave to estimate how the atmosphere will change with time. These models are capable of simulating hurricanes, though many make rough approximations of the complex cores of storms.

Some forecast models are run as ensembles, in which many versions of the same model are made by slightly tweaking initial weather conditions — for example, shifting the starting location of a hurricane by a few miles. Small differences can have big long-term impacts, so the way the ensemble members spread out with time gives a sense of forecast uncertainty. Averaging ensemble members also can decrease errors.

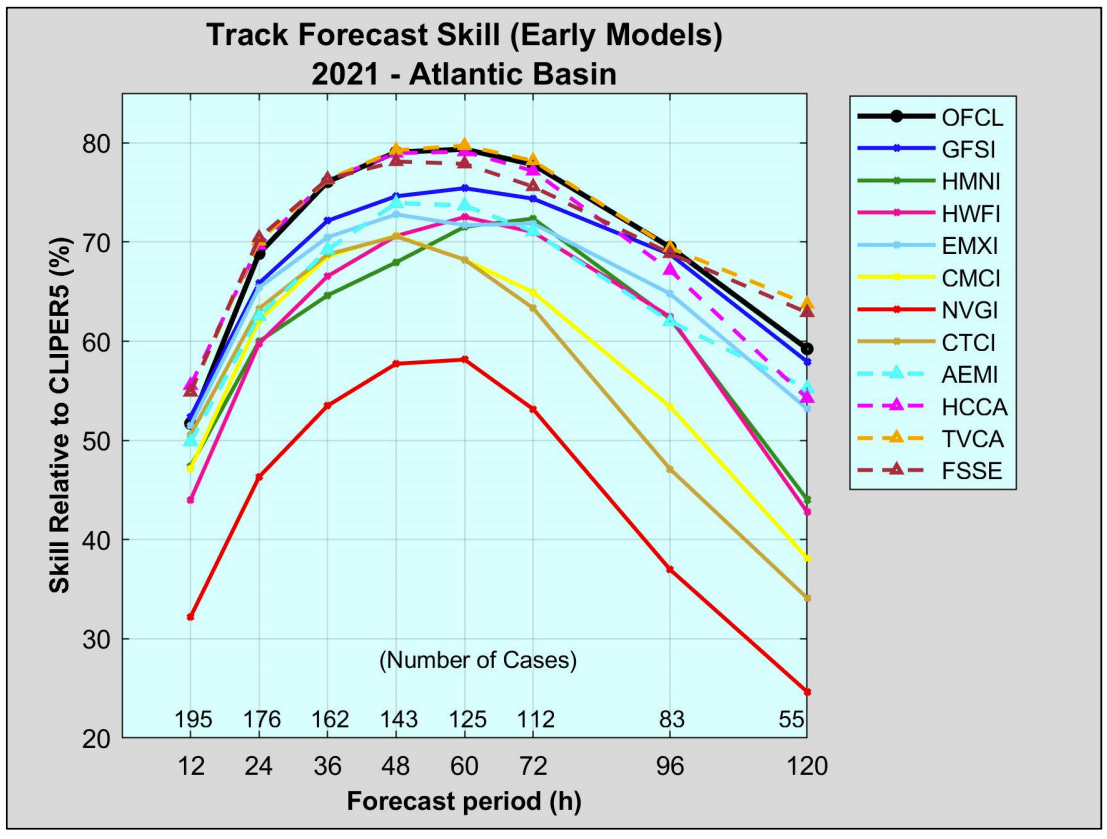

The output of the various computer models and ensemble members is often shown as colorful lines of possible hurricane tracks. This is colloquially known as "model spaghetti,” and that pasta is not all equally delicious. Recent upgrades to some models have resulted in improved forecast performance over the last couple seasons, so there are some key changes in the 2022 hurricane model power rankings below. All validation data is taken from the 2021 season NHC Forecast Verification Report.

Without further ado:

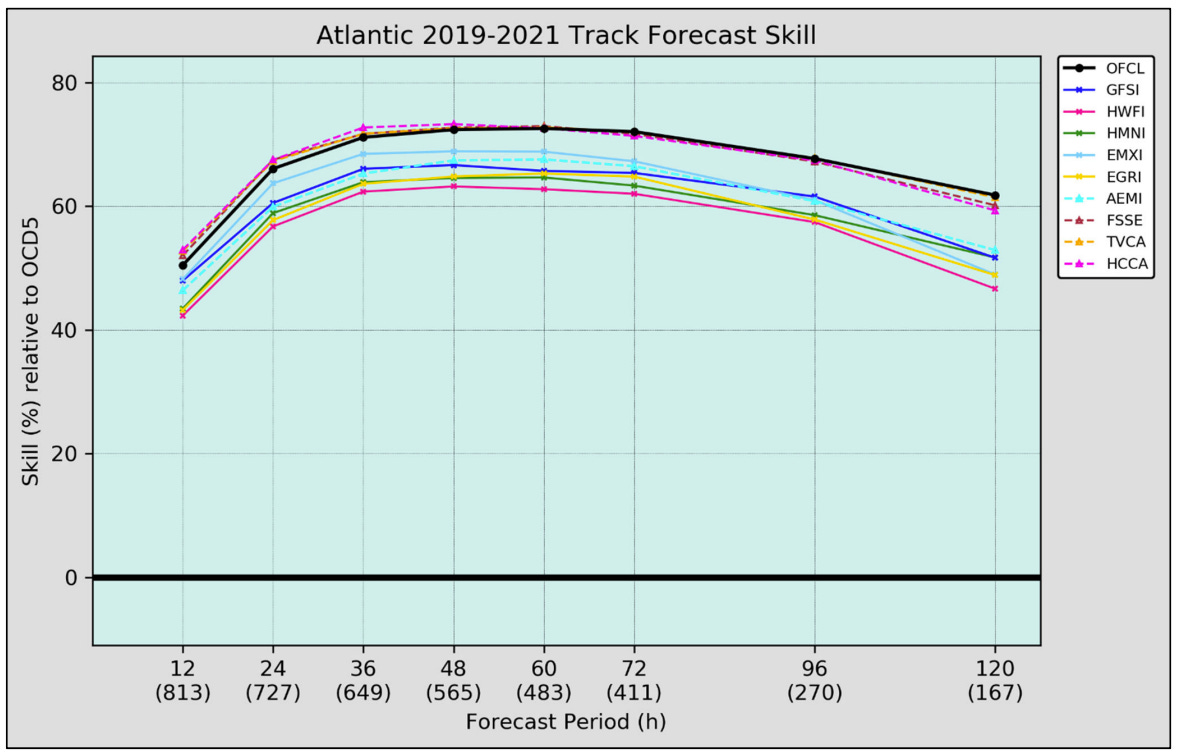

Tie-1. American (GFS). GFS output is free and probably underpins the forecasts on your weather app. This model underwent an upgrade a few years ago that improved its reliability for hurricane forecasts, especially for stronger storms. The GFS was the most skillful single track model for the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season at all lead times, and its ensembles are much improved relative to previous iterations. The GFS and GFS Ensembles still get tripped up with false alarms in developing storms, though in a somewhat predictable way tied to specific geographic biases.

Tie-1. European (ECMWF). The European model remains the most skillful in predicting global weather patterns due to better assimilation of weather observations and superior processing power. However, “King” Euro has struggled in the Tropics in the last few years, taking some notable Ls like incorrectly forecasting the destruction of Houston during 2020’s Hurricane Laura. The “King” is decidedly human, though its 2019-2021 average track errors are still a little less than the GFS for most lead times. Still, the crown has to be shared for the first time in these rankings. Drama.

3. British (UKMET). The UKMET ranks second-lowest in overall global weather pattern forecast errors. For tropical weather, it is an independent opinion that can be uniquely correct but often has a west bias for track. The UKMET also runs for a shorter forecast period, and its ensembles are delayed relative to other models, making its predictions a little less useful to forecasters.

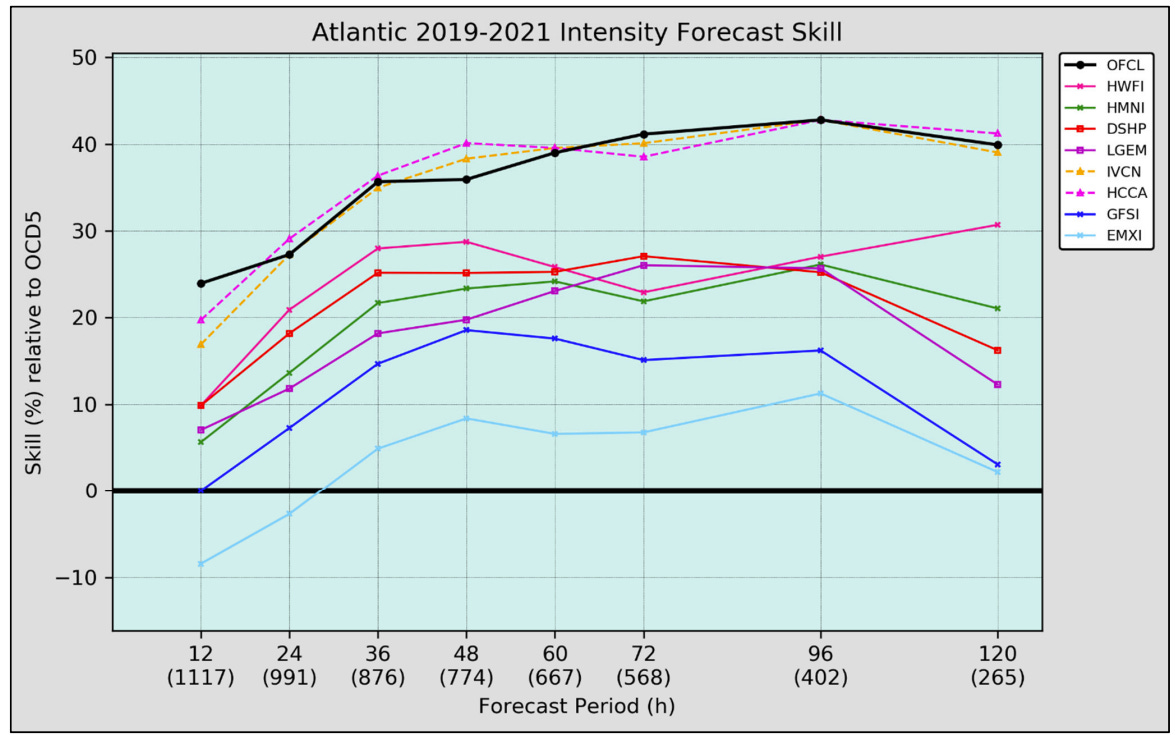

Tie-4. HMON. The HMON is a refurbishing of an earlier American hurricane model, and sometimes wanders off on its own with odd predictions. However, HMON actually was once again better than the comparable HWRF model for track forecasting in 2021 at some lead times, and led the pack for individual models intensity prediction skill.

Tie-4. HWRF. The flagship American hurricane model is designed to incorporate a leading-edge understanding of what goes on in the intense inner core of a storm. The HWRF provides useful guidance in favorable environments for development, but is biased towards over-strengthening storms in marginal ones. Its track forecasts also underperformed in 2021 at both short and long lead times.

Below here, the value over replacement model (VORM) drops below one, meaning (in my opinion) no value is being added to a forecast for the additional information.

6. Canadian (CMC). The Canadian model is a reasonable performer for jet stream pattern forecasts. A 2019 upgrade improved its performance in the Tropics from laughably bad to merely inessential.

7. COAMPS-TC. A hurricane-specific model from the Navy. A few hits, a lot of misses.

8. NAVGEM. It is better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to post output from the NAVGEM on social media and remove all doubt.

9. American Mesoscale (NAM). The NAM is not a tropical model and is known for comically bad intensity forecasts. Worst of the worst for hurricanes.

Unranked: HAFS. An advanced hurricane model currently under development, from time to time experimental HAFS output is released by NOAA. Look for HAFS to climb the charts when it’s ready for prime time in a few years.

So, now you know which models are poised to join the SEC, and which will languish in the Mid-America Conference. However, the real takeaway from this exercise is that last year and every year, National Hurricane Center forecast skill led all individual models and met or exceeded the best multi-model blends at all lead times. Average NHC forecast errors also continue to decline: the average NHC five-day forecast in 2020 was more accurate than their two-day forecast in 1990. NHC forecasts are also far more consistent in their precision than any models, which can and do pinball about ridiculously when the chips are down. In contrast, NHC forecasts usually have measured changes each six hours.

Overall, while invaluable to specialists, for the public, uninterpreted computer model hurricane forecasts don’t add value and can cause unnecessary heartburn, especially as the scariest runs tend to find the most eyeballs. In terms of forecast accuracy and consistency, what it takes to be number one isn’t some magic model, but the professional discernment to blend multiple pieces of evidence from guidance and observations into a steady forecast; the NHC does this extraordinarily well. Keep that in mind in the months ahead when your sharing finger gets twitchy, and keep watching the skies.

Next update: Our regular daily briefing will resume tomorrow for paid subscribers.

Not affiliated with J.D. Power & Associates.