Front Toward Enemy: Hurricane Watch Column for October 18th

Cold fronts are cooling the Gulf, and there remain no U.S. threats on the map. A final burst of tropical activity is possible starting in 12-15 days.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, plus coverage of every U.S. hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions.

On September 29th, I advised Floridians reeling in Helene’s wake and nervously monitoring what would become Milton to “pause the deployment of your 15’ lawn skeletons, werewolves, and Cthuls-hu until the forecast gets a little clearer.”

While that forecast unfortunately did get clearer in a bad way, the good news is that today I can finally give the people of Florida and the Gulf Coast what they truly want: license to let those $449 animatronic ghouls go wild. I can’t rule out a repeat of the Great American Clownpanic of 2016 this spooky season, but I am confident that the next week and a half will be free of the conepanics associated with tropical threats to the continental United States. However, at longer range, hurricane season is not over.

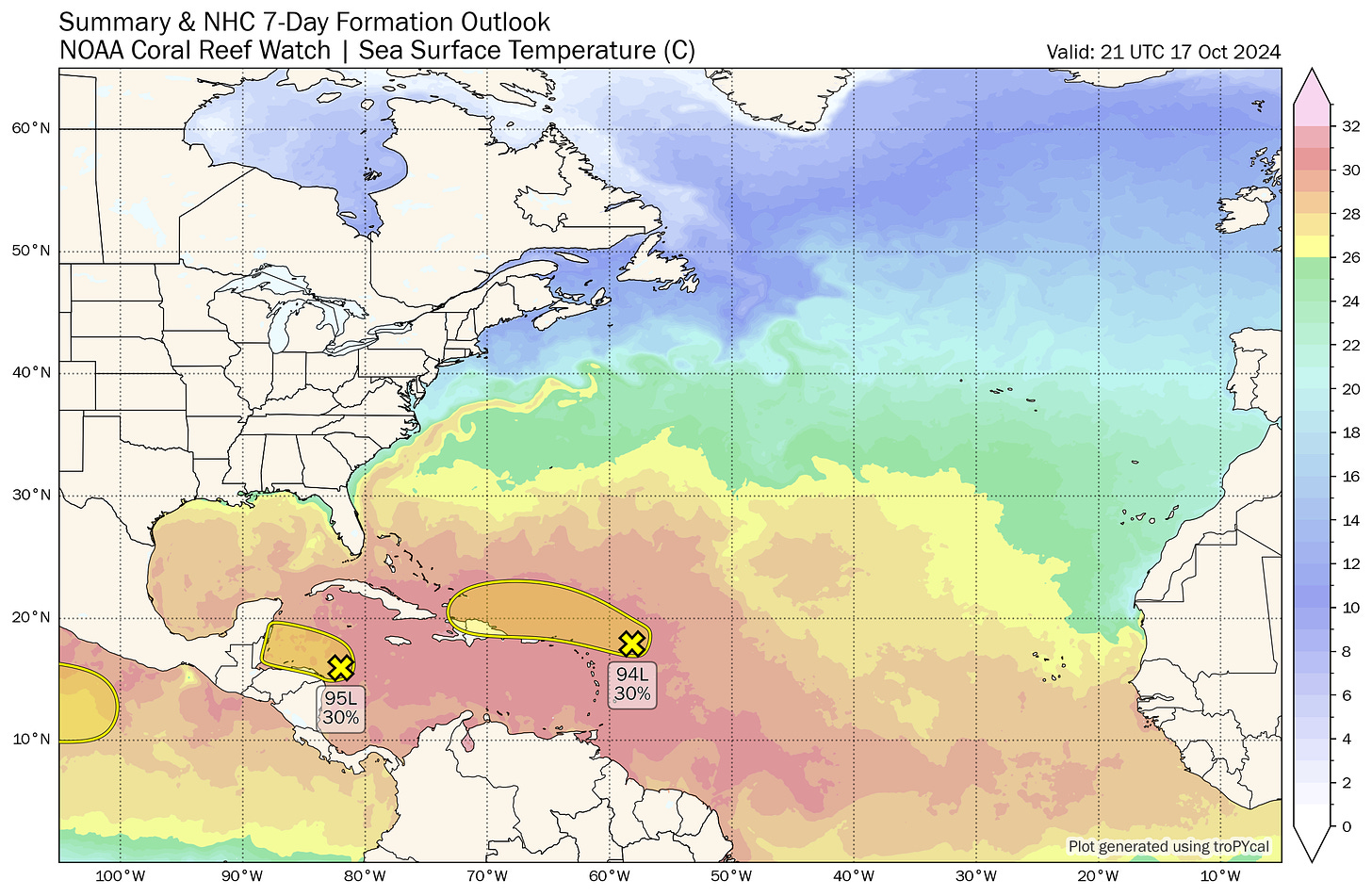

Today, there are two areas to keep an eye on for tropical potential development through the weekend. The first of these is a tropical wave forecast to pass north of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola through Sunday. This wave stirred up consternation earlier in the week as the NHC’s Tropical Weather Outlook seemingly put it on a general trajectory towards the Southeastern U.S. In reality, there never was an actual threat to land due to a protective cold front that will cause increasing wind shear over the wave starting Monday. This system has less of a chance of any development than it did a few days ago, and whatever is left of it after tangling with the shear should dribble harmlessly into the western Caribbean next week.

The other system is a broad area of convection and rotation that will move across the western Caribbean this weekend. While I don’t blame you for an involuntary shudder at the words “rotation” and “western Caribbean” in close proximity to one another, in this case a strong ridge of high pressure developing over Florida will guide this disturbance into Central America by Sunday. While this system is the better bet for the possible development of short-lived depression or storm this weekend, it also poses precisely zero threat to the Gulf Coast.

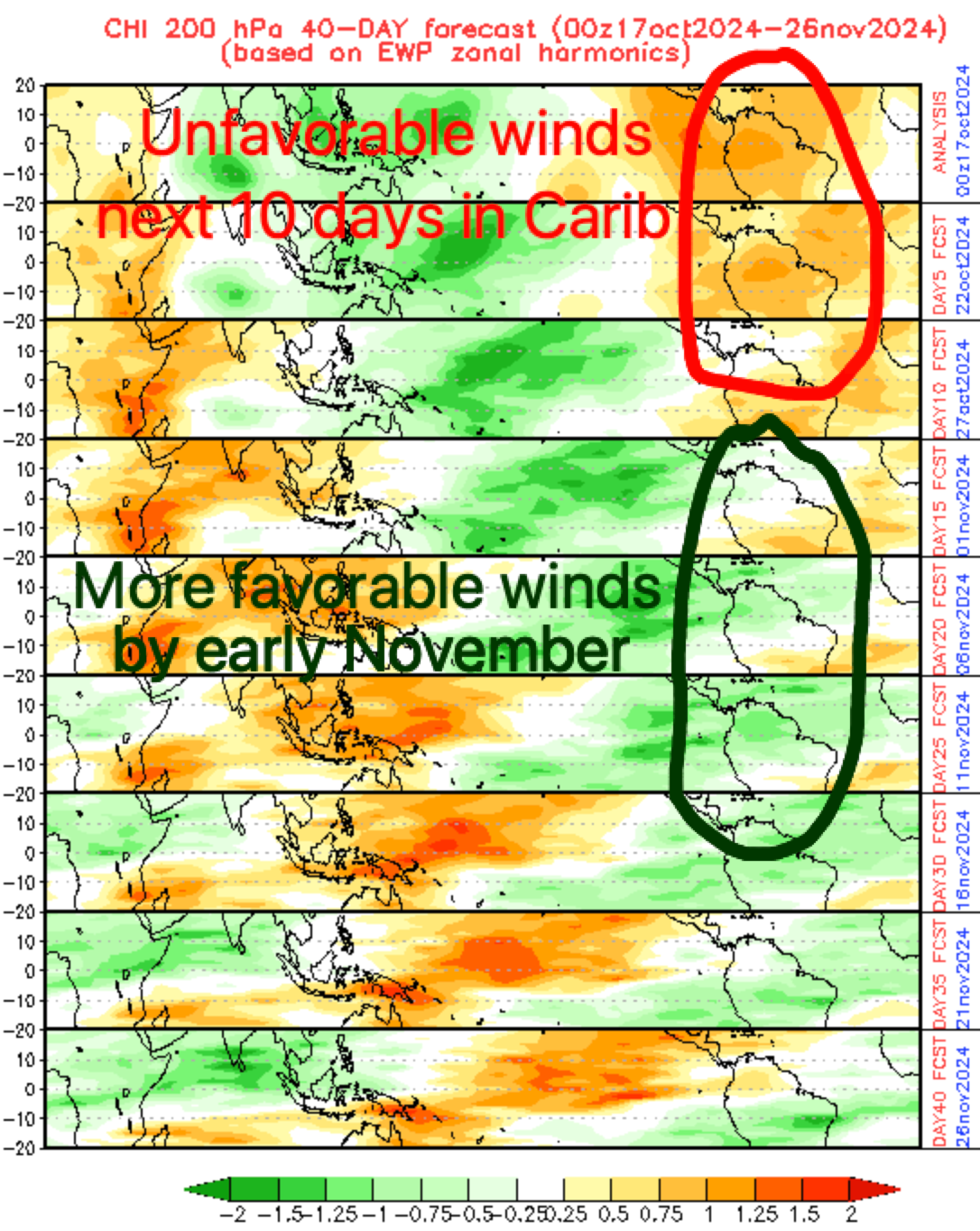

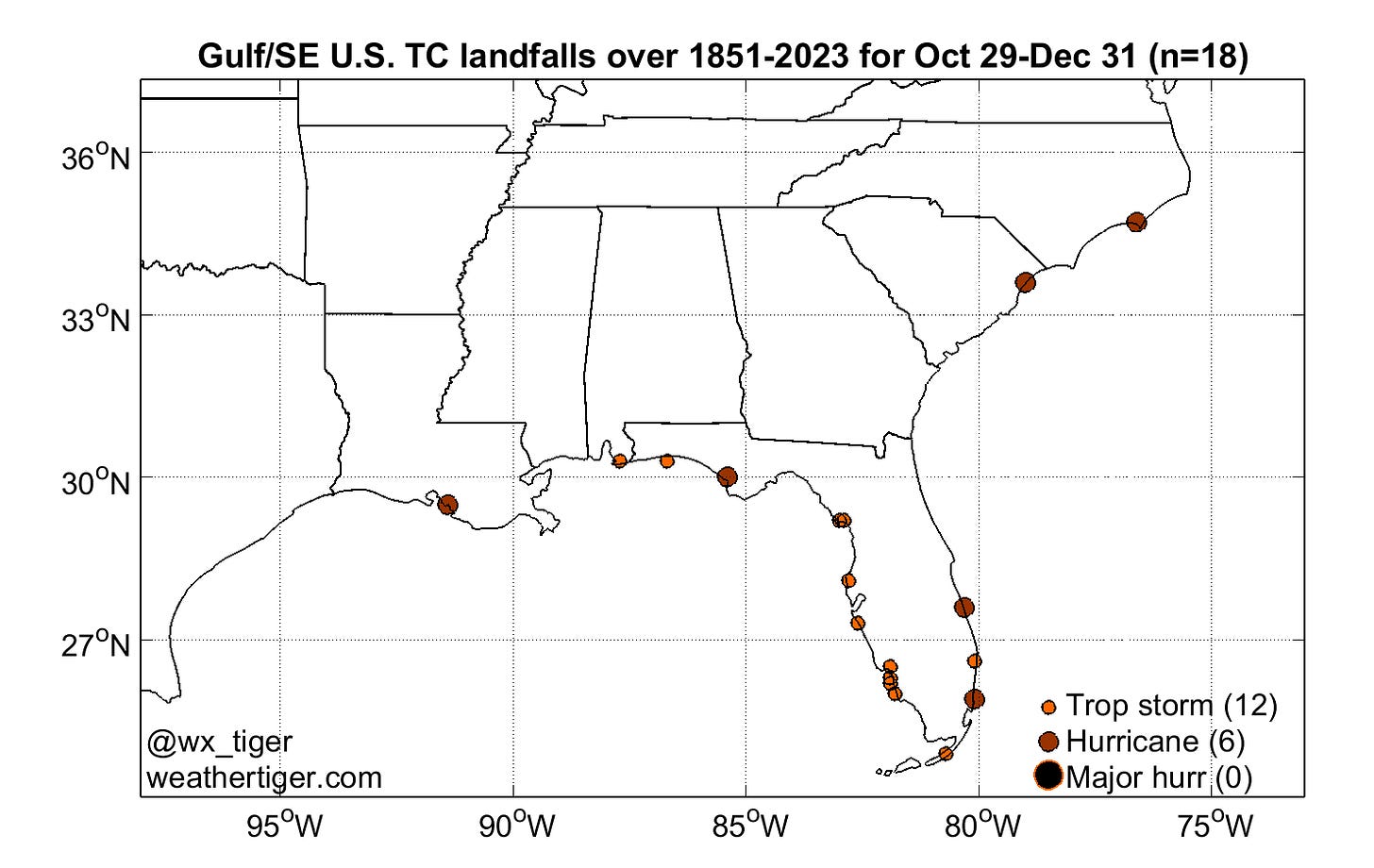

The lack of current U.S. threats plus unfavorable upper-level winds for tropical development in the Caribbean and Gulf next week should carry us through late October without further incident. That is meaningful, because the latest Florida Category 3+ landfall, the 1921 Tarpon Springs hurricane, occurred on October 25, and a major hurricane has never struck anywhere in the U.S. after October 28. Only about 2% of annual U.S. landfall activity occurs beyond that date: about 20 storms in around 170 years, seven of which were hurricanes. Most late season landfalls are focused on South Florida, with Category 2 Hurricane Kate in the Panhandle a notable exception.

Historical U.S. landfall rates decline so steeply at the tail end of October that there ought to be a runaway truck ramp at the bottom of it for two reasons. First, sea surface temperatures near the continental United States fall as cold fronts begin to regularly cross the Gulf and western Atlantic. In 2024, Helene and Milton have already cooled the eastern Gulf by 3-5F in the past several weeks, and the potent cold front that dropped lows into the upper 30s and led the National Weather Service to issue an Uggs Warning for North Florida college campuses on Thursday morning will cool it off even further.

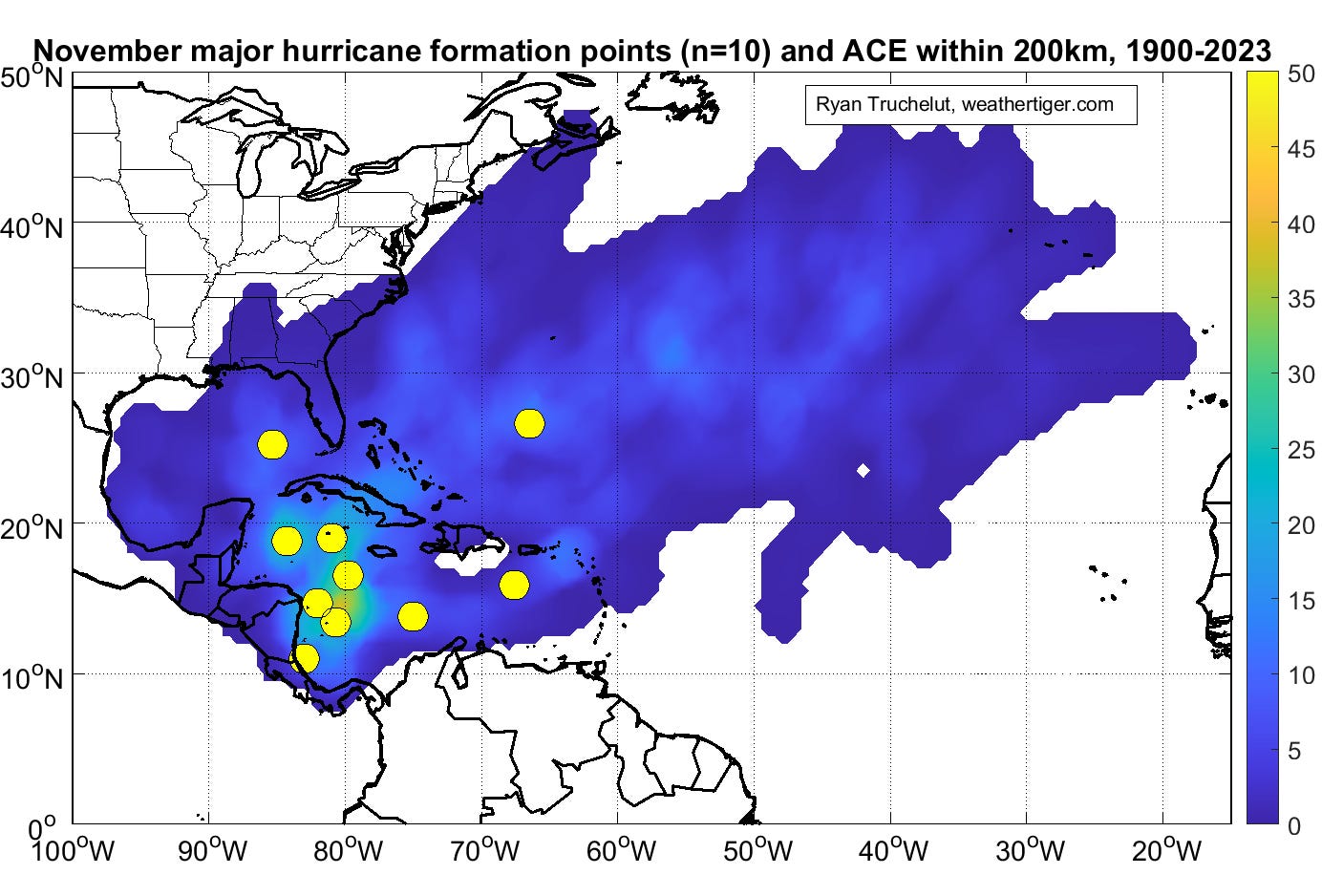

Shelf waters north of Tampa Bay are already seeing sea surface temps in the 70s, which is too tepid to long sustain tropical cyclone activity. Additionally, the steady southward progression of mid-latitude winds blowing from west to east both leads to increased wind shear and to a tendency for late-season tropical activity originating in the Caribbean to turn northeast across the Greater Antilles, rather than head northwest or north into the Gulf in late October and November.

So, history tells us that it’s a much heavier lift to bring a storm to Florida in the final month and change of hurricane season than it is in early or mid-October. However, much as the Joker refuses to play by society’s rules (including the rule that a movie should be “successful” or “good”), 2024 has defied the strictures of climatology time and again and may do so once more. There are solid indications that of a couple of weeks of unusually favorable upper-level winds are coming to the Caribbean starting at the very end of October and extending through mid-November. With the Caribbean Sea still blazing hot, it’s possible that one or two more named storms could be squeezed out of this set-up. That’s not to say that these would be U.S. landfall threats—history suggests they wouldn’t be—but it’s worth keeping an eye on the October 30 through November 10 window just in case.

With luck, any such storms will remain someone else’s problem, so next week’s column is the final regularly scheduled one of the 2024 season. Per tradition, I’m once again inviting you to Stump the Tiger by sending me questions to be answered in this space next week. I’m planning on a reader-led overview of Helene and Milton, so queries about those two historically awful storms will be prioritized. As a reminder, please keep all questions reality-adjacent, or failing that, at least on the amusing rather than the appalling side of lunatic fringe. Until then, keep watching the skies.

I just started listening to Audibles version of George R. Stewart's book, Storm. I find it quite interesting if you have never read it. Long before your time. I was only two when he wrote it in 1941. First example of Eco-Fiction they claim.

The end is in sight!!