Control of the Board: WeatherTiger's Weekly Column for June 8th

Unpacking Alex, what makes a tropical cyclone a tropical cyclone, and the emotional consequences of broadcast television.

WeatherTiger’s June free trial of our premium daily forecast service has ended. If you are already a paid subscriber or signed up during PTC 1/Alex, thank you for your support.

If you are not already a supporter and would like continued comprehensive coverage of the 2022 hurricane season, please consider signing up for a paid subscription. You’ll get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings each weekday, plus weekly columns like this one, full coverage of every U.S. hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast, and the ability to comment and ask questions, all for just $7.99.

What is a tropical cyclone?

A common question in the wake of the disturbance eventually known as Alex is why something that looked and felt like a weak tropical storm in weather terms did not get a name until after it exited Florida. While this distinction had no impact on impacts, many were puzzled by its continued designation as a “potential tropical cyclone” through Saturday. Befitting its namesake quizmaster, let’s use the case of Tropical Storm Alex to transform that question into an answer in the form of a question.

Full disclosure: while I am a former Jeopardy! contestant, unlike the strong track record of other meteorologists on the show, the only Jeopardy! record I hold is for fewest wins, with zero. Admittedly, this is a record I share with many others, although I may be unique in my response of, “What is a unicorn?,” to which I received a brutal, Canadian “ooh, sorry” from Alex T. The day was not mine.

Life regrets notwithstanding, the precipitation impacts of pre-Tropical Storm Alex on South Florida were potent, though not potable. Southwest and Southeast Florida saw over 24 hours of continuous moderate to heavy rainfall between Friday morning and Saturday afternoon, with particularly torrential rains over coastal Miami-Dade and Broward Counties. In general, rainfall accumulations through Sunday in metro South Florida were 4-8”, with local totals of up to 15”.

This caused widespread street flooding, which has since been prolonged in some spots by continued excessive rains in Alex’s wake. There was also a potpourri of low-end tropical-storm-force wind gusts in the Keys and coastal South Florida over the weekend, including a gust of 52 mph on Virginia Key in Biscayne Bay. Thankfully, no reports of tornadoes. All of these impacts, typical of early-season tropical activity, would likely have been little changed had they been delivered by a Tropical Storm Alex rather than Potential Tropical Cyclone 1.

However, tropical meteorology is not Outback Steakhouse. There are rules. The forecasters at the National Hurricane Center have a scientific definition of what constitutes a tropical cyclone, a term encompassing tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes. In order to be a tropical cyclone, a system must:

Have a closed, cyclonic circulation. This means there are surface winds from all compass points within the system. PTC1 satisfied this on Thursday.

Be distinct from fronts. A tropical cyclone is not connected to large horizontal differences in temperature across the storm. The Caribbean in June isn’t a hotbed of cold fronts, so this criterion was met early for PTC 1.

Have a “warm core.” Tropical cyclones are distinctly warmer than their environment, particularly aloft, due to their extraction of oceanic heat energy via condensation. Also not a issue with PTC 1.

Maintain organized deep convection. Here’s where PTC 1 ran into trouble. While it produced plenty of storms on Friday and Saturday, they pulsed and faded, and were strongest on the eastern fringes of the circulation.

Have a well-defined center. This was the real disqualifier. Rather than a single, organized center of circulation at the heart of the surface windfield, PTC 1 had a swirl in the Keys, a swirl by Fort Myers, and a swirl off the East Coast on Saturday.

Disorganized, intermittent convection and too many swirls jockeying for supremacy meant PTC 1 did not meet the definition of a tropical cyclone until it further consolidated east of Florida. The NHC sells no wine before its time, so Alex was thus named on Sunday and no earlier.

Sometimes, these strictures create a challenge in threat communication for a system that isn’t technically a tropical cyclone yet, which is why the “potential tropical cyclone” status was created. That designation allows the NHC to issue watches and warnings in anticipation of expected tropical hazards, and they did so in a timely and accurate fashion during PTC 1.

As with any human endeavor, an element of subjectivity does creep into the process, particularly in how long a system must “maintain” deep convection to qualify as a tropical cyclone. I’ll take a closer look at the recent increase in short-lived cyclones and whether those standards have changed in next week’s column.

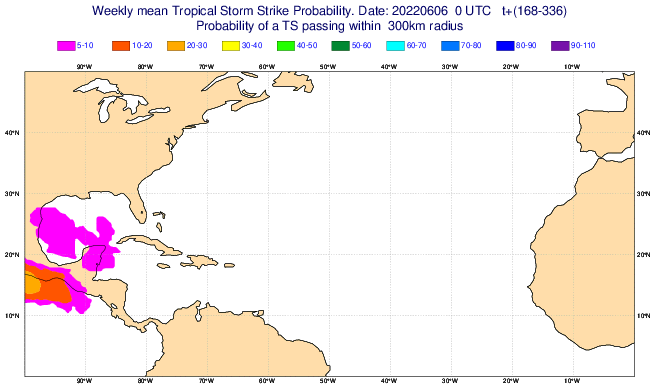

In the meantime, no further tropical cyclones are expected to develop in the next five to seven days. A plume of Saharan dust is putting the kibosh on Atlantic convection, and anything that tries to spin up near Central America next week would be shunted west into the Eastern Pacific.

And so, please rise for the Jeopardy! think music: “This non-frontal, well-organized closed circulation has a warm core ringed by deep convection.” What is a tropical cyclone, Alex?

Keep watching the skies.