Atlantic's Next Top Model: Hurricane Watch Weekly Column for July 11th

How do the leading hurricane models stack up against each other, and the NHC?

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused tropical briefings each weekday, plus weekly columns, full coverage of every hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions for $49.99 per year.

In 2017, Dippin’ Dots changed their slogan from “The Ice Cream of the Future” to “Taste the Fun,” a tacit acknowledgement that we were, at long last, living in the future. Unfortunately, The Future has been both over- and underwhelming, possibly because the greatest minds of a generation spent the 2000s cramming the maximum number of blades on razors and the 2010s training people to argue on the Internet for minimal profits.

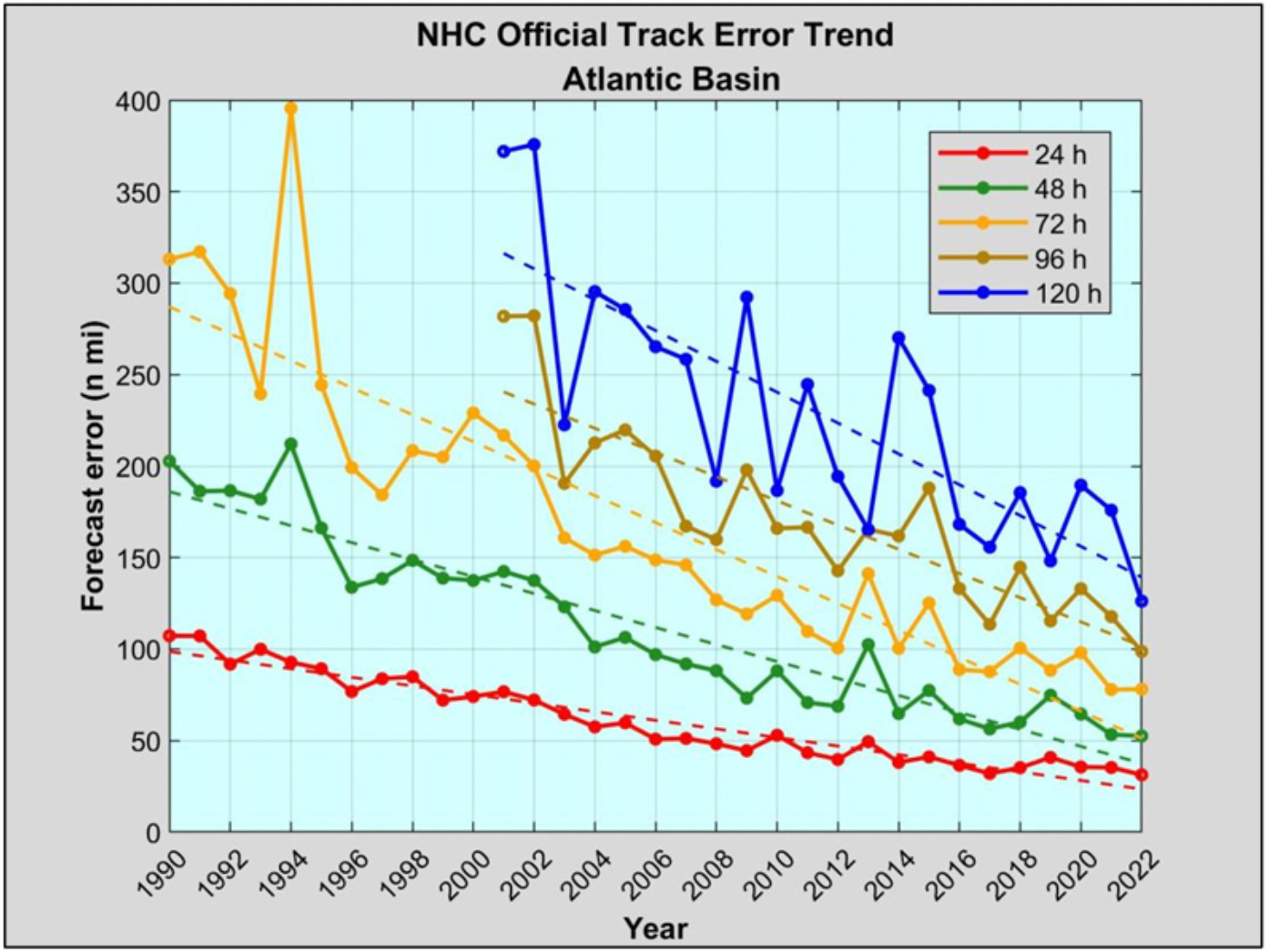

One of the handful of non-disappointing aspects of the future has been steady progress in hurricane forecast accuracy, in which computer models have been an instrumental tool. Over the past few decades, the National Hurricane Center’s one- to three-day track forecast errors have diminished by 75%, with reductions of about 60% over the past 20 years at four- and five-day lead times. In 2022, NHC track forecasts set accuracy records at most lead times.

With the Tropical Atlantic currently in a mid-summer lull, let’s chat about those models before they go viral on the various rage platforms as storms threaten. This week is a good opportunity to do so, as the only region to watch is a non-tropical area of low pressure well east of Bermuda. There is a fair chance that this system takes on some subtropical characteristics as it meanders the open Atlantic over the next two to four days before moving east, but is no threat to land. Otherwise, the Atlantic is dusty, quiet, and likely to stay that way for at least another week. The eastern Main Development Region may start to rouse in 8 to 12 days heading into late July.

Meteorologists can make predictions like that with confidence thanks to computers’ incredible facility with repetitive math problems. In a nutshell, computer models use information about current weather conditions and the physics equations that describe fluids to estimate how the atmosphere will change with time. These models are capable of simulating hurricanes, though many make rough approximations of the complex physics of the eyewall.

Some forecast models are run as ensembles, in which many versions of the same model are made by slightly tweaking initial weather conditions — for example, shifting the starting location of a hurricane by a few miles. Small differences can have big long-term impacts, so the way the ensemble members spread out with time gives a sense of forecast uncertainty. Averaging ensemble members also decreases errors. The output of the various computer models and ensemble members is often simplified into a herd of attractive lines showing possible hurricane tracks, colloquially known as "model spaghetti."

Yet there is more to modeling (and life) than being really, really ridiculously good-looking, and not all spaghetti is equal. Here are some tiers to use as a general rule of thumb this season, with validation data taken from the 2022 season NHC Forecast Verification Report.

Tier 1: Fine Cuisine

European (ECMWF). The predictive skill of the European model for global weather patterns remains superior due to better ways of incorporating observations, backed by world-beating computing power. For hurricanes, “King” Euro narrowly has the best average track skill over 2020-2022; it also did relatively well with Ian. Still, kings are human, and the Euro is a poor performer in intensity forecasting. Another recent upgrade increasing the number and resolution of ensemble members may help with that in 2023.

American (GFS). GFS output is free and probably underpins the forecasts on your weather app. This model underwent an upgrade several years ago that improved its reliability for hurricane forecasts. After a pacesetting performance in 2021, the GFS and GFS Ensembles struggled a bit in 2022, including a consequential miss to the northwest with Ian. Still, the GFS is close to the Euro in average track skill over 2020-2022, and outperforms all other non-hurricane-specific models in intensity forecasting.

HAFS. HAFS is a next-generation NOAA model moving from experimental to operational status in 2023. Putting a rookie in tier 1 may be a bold choice, but HAFS is a major step forward that combines the strengths of global and hurricane-specific modeling and has performed well at both track and intensity prediction over the last several years of testing. We are watching its career with great interest.

Tier 2: Olive Garden

HMON. The HMON is a refurbishing of an older American hurricane model, and sometimes wanders off on its own with odd predictions. Despite this, HMON actually led the pack for track forecasting in 2022 between two and four days’ lead time, and has outperformed the newer HWRF in average track errors since 2020.

British (UKMET). The UKMET ranks second-lowest in overall global weather pattern forecast errors. For tropical weather, the Ukie is an independent opinion worth considering—it consistently took Ian’s into Southwest Florida—but often has a westward bias. The UKMET’s shorter forecast period, delayed ensembles, and limited availability also make it a little less useful to forecasters.

HWRF. An American hurricane model designed to simulate the complex inner cores of hurricanes. Led all models in three- to five-day intensity forecasts last year, despite a perpetual bias for over-strengthening storms in marginal environments. HWRF track forecasts underperformed in 2022, swinging much too far west with Ian, and 2020-2022 average errors are worse than the UKMET and HMON models.

Tier 3: Expired Pasta

Canadian (CMC). The Canadian model is respectable in the mid-latitudes, and was upgraded a few years ago with the hopes of improving performance in the Tropics. This expectation has proven, like Canada’s other main export, to be smoke. Does not add forecast value.

Navy (NAVGEM). The NAVGEM is a useful model, in that if someone posts or seriously discusses it, you can be certain that person is either trying to scare you or has no idea what they are talking about.

American Mesoscale (NAM). The NAM is not a tropical model. Strengthens tropical depressions into hurricanes and hurricanes into the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Ignore it.

Tier 0: The “Surprise” Winner

NHC official forecast. Last year and every year, the official National Hurricane Center forecast bested all individual models and equaled the best model blends at all lead times. Crucially, NHC forecasts are also far more consistent than any individual model, which typically jump around 100 miles or so each six hours at a four-day lead time. NHC four-day forecasts are not only more skillful than individual models, but shift less than 60 miles on average between advisories. Accurate, dependable.

Overall, computer model hurricane forecasts are not very helpful for the public, particularly as the most extreme runs from any tier find the most eyeballs. This was true in 2003, it’s true now, and it’ll likely be true in 2043 when Dippin’ Dots are marketed as “The Ice Cream of the Past.” The good news is, unless you are a professional forecaster, you really don’t need the heartburn of looking at models. While an individual model may outperform the NHC for an individual storm, over time the NHC’s meticulous and balanced approach wins. Keep that in mind this season when and if things get scary, and keep watching the skies.

Very interesting and fact-filled. Thank you.