WeatherTiger's 2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season Fall Outlook

The latter third of Atlantic hurricane season looks busy, but hopefully not 2020-busy.

WeatherTiger’s updated hurricane season outlook is provided free to all subscribers. To get our complete storm coverage, upgrade to premium for as little as $8 to get daily forecast briefings, in-depth forecasts and videos during Florida hurricane threats, live landfall coverage, expanded seasonal outlooks, and the ability to comment and ask questions.

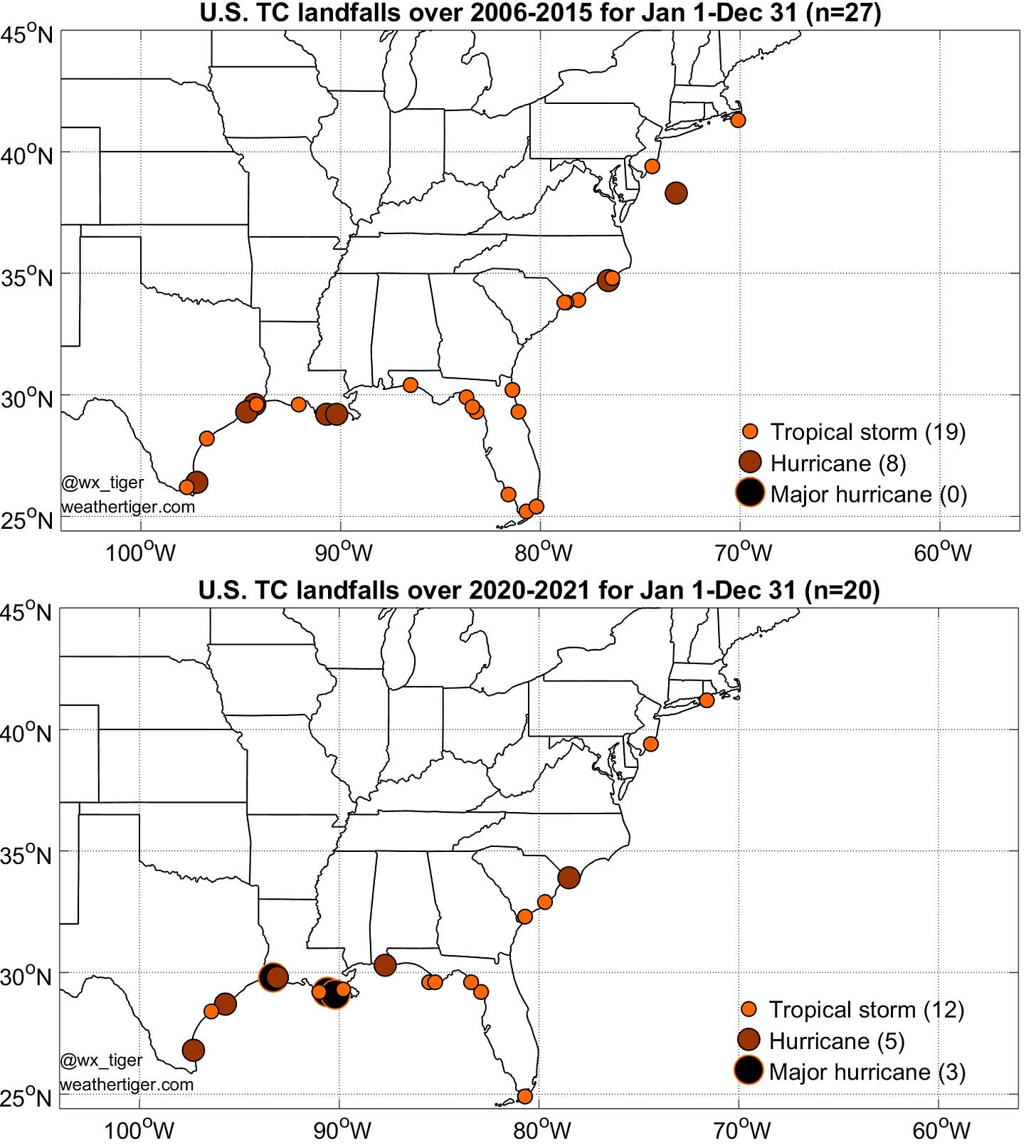

Since May 2020, forty-five tropical cyclones, twenty hurricanes, and ten major hurricanes have developed in the Atlantic.

Twelve tropical storms, five Category 1 or 2 hurricanes, and three major hurricanes have made landfall in the continental United States.

This is, in scientific terms, a lot.

In fact, the last 480 days have seen almost as much U.S. hurricane activity as the entire decade between 2006 and 2015. And despite this unrelenting meteorological enfilade, there are still miles to go before the Atlantic sleeps. As measured by historical landfalls, the final third of the 2021 hurricane season remains ahead.

Heading into the last 10 days of September, Atlantic hurricane season shifts gears like an abandoned K-Mart transforming into a Spirit Halloween superstore. At this time, the frequency of “Cape Verde”-type storms that develop in the eastern Atlantic and sometimes threaten the U.S. East Coast declines, and the loci of hurricane development shift into the Caribbean and western Atlantic— closer to land.

Currently, the Tropics are in a rare interregnum as this change gets underway. The focus this week has been on Gulf Coast, which has been dealing with excessive rainfall from Nicholas. Much like the acting style of its namesake Nic Cage, Nicholas was uncomfortably intense and disregarded norms of personal space as it intensified to Category 1 hurricane strength just off the Texas coast late Monday.

Since then, Nicholas’ remnant low has moved only slowly east, spreading 5-15” accumulations from eastern Texas to far western Florida. Nicholas is winding down, but another 1-4” is possible over the Deep South and eastern Gulf Coast through the weekend in intermittent bands of storms.

Elsewhere, U.S. threats are minimal for the moment. A broad area of low pressure east of the mid-Atlantic is likely to become a tropical storm as it accelerates northeast and away from land over the weekend. This system may strengthen further in the North Atlantic early next week, but it is not a threat to U.S. interests.

Of slightly greater concern is a wave in the Tropical Atlantic, approximately halfway between the Lesser Antilles and West Africa. This wave is taking its time getting organized due to interaction with another tropical wave to its west, but slow development of a tropical depression or tropical storm is also expected by early next week.

The northern Windwards and Puerto Rico will need to keep an eye on this wave for potential impacts on Monday or Tuesday, though shear is expected to increase as the wave nears the islands, likely capping intensity. The good news is that a high-pressure ridge over the U.S. East Coast is likely to shift east into the central Atlantic towards the end of next week. This move should open an escape hatch for anything that develops to eventually turn north into the open Atlantic. Still, there’s a lot of moving parts at play, so it’s worth watching this wave until forecast confidence is stronger.

2021 Fall Outlook

This rare breathing room brings an opportunity to take stock of what the rest of the 2021 hurricane season may have to offer. While two-thirds of Florida’s historical hurricane activity occurs prior to the last week of September, fall remains a risky time for the state.

Florida hurricane climatology has three distinct peaks. The first, in June, is driven by weak, wet Gulf Coast storms; the second in early September is associated with the overall peak of the season and powerful, long-tracking threats to South Florida.

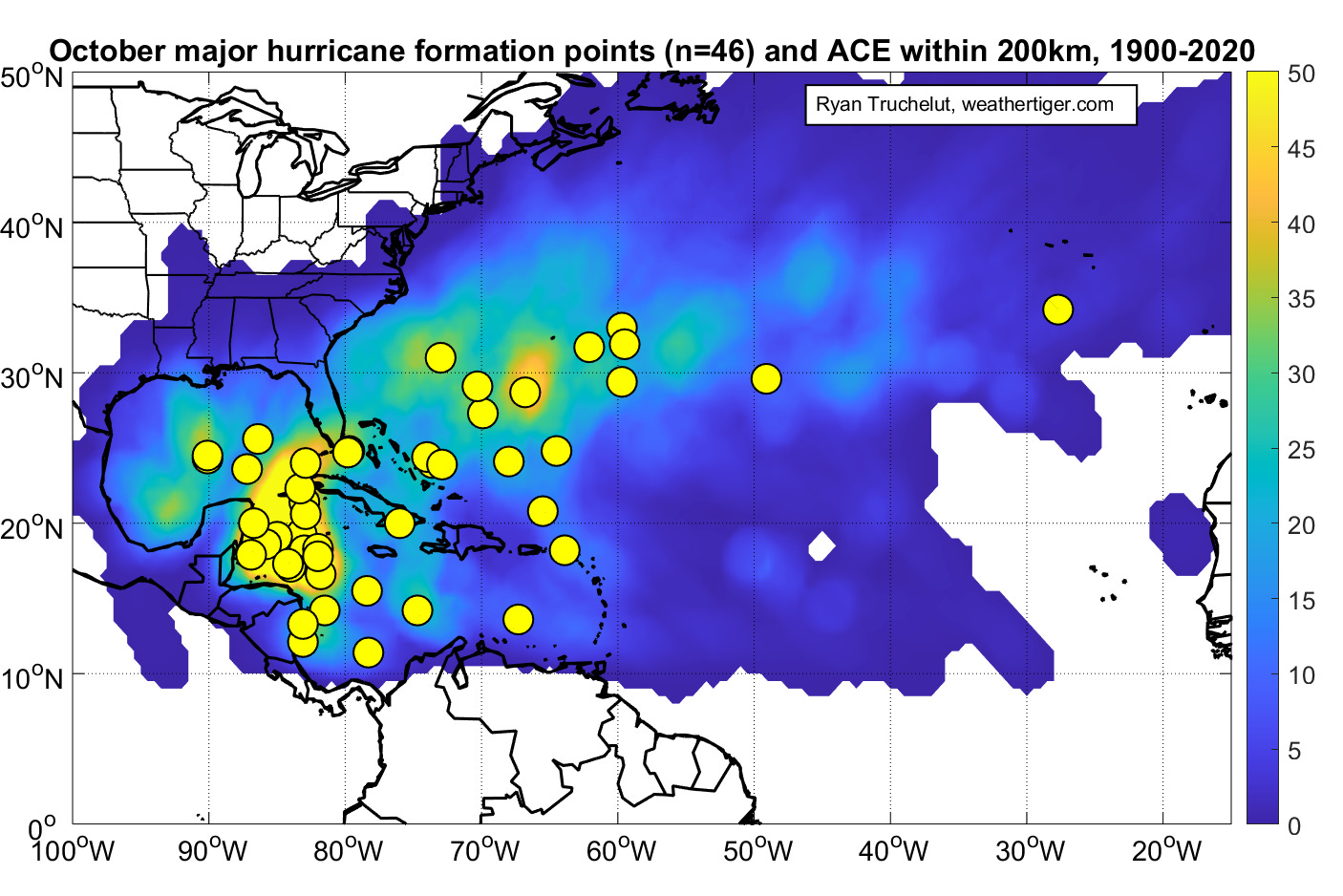

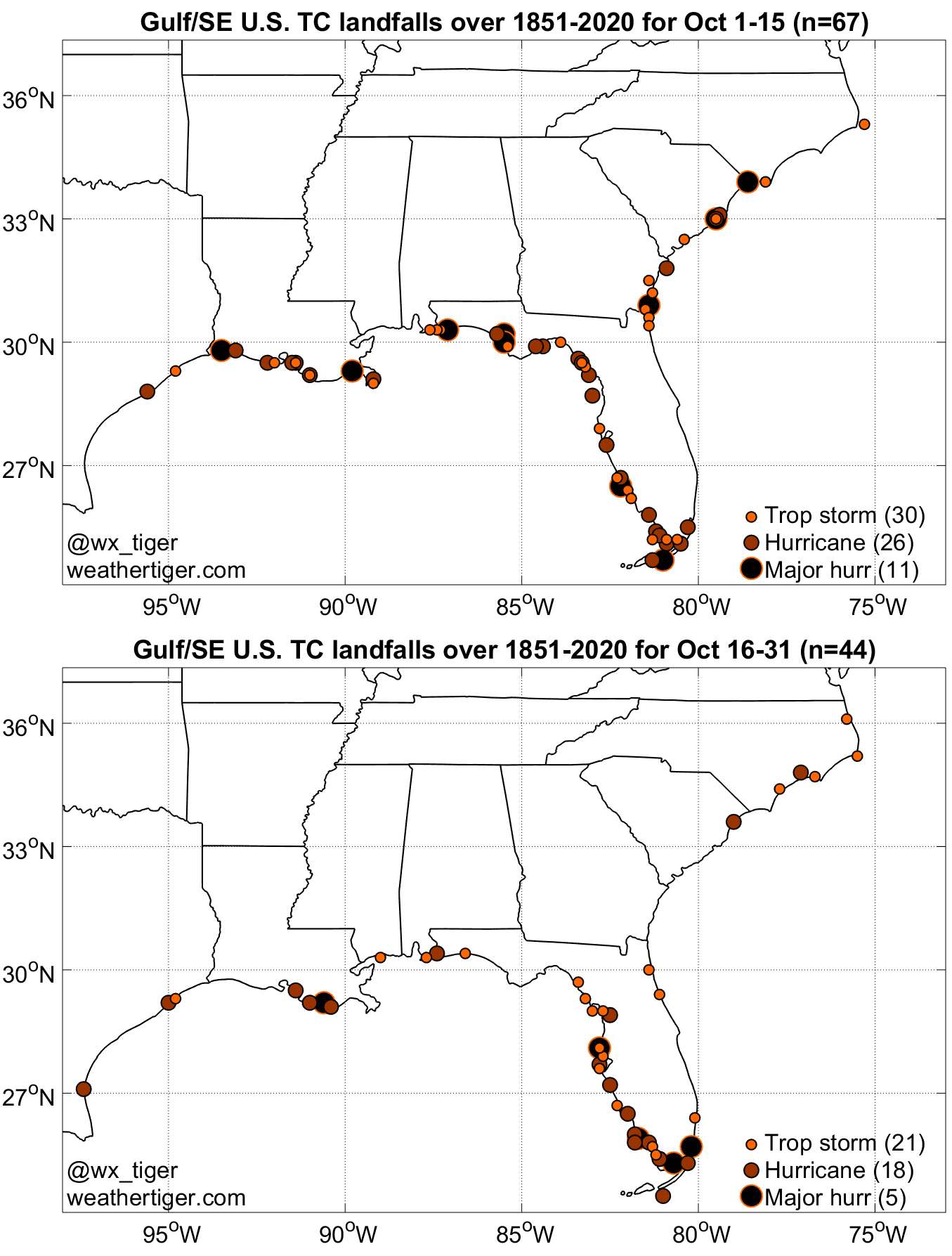

The third peak is in mid-October, when late-season landfalls cluster on the Florida Gulf Coast. In Southwest Florida, hurricane impacts are as common in October as September, due to fall storms moving north and northeast out of the western Caribbean. Historical landfall points split between early October and late October show that the greatest risks shift south for the second half of the month, and begin to tail off in North Florida after mid-October.

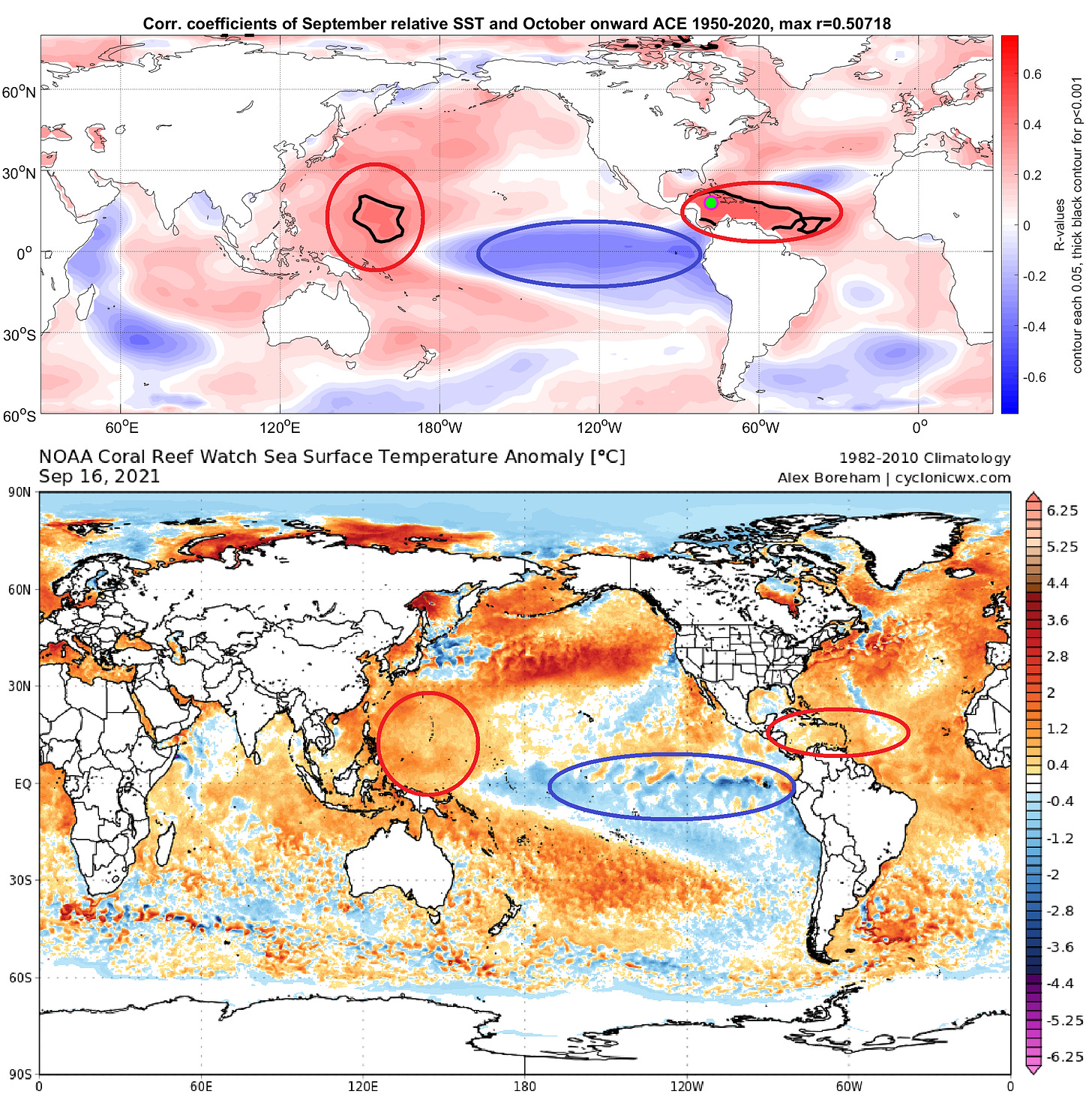

Two factors have the strongest historical relationship with late season tropical activity: Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SSTs), and El Niño/La Niña state in the Pacific.

With late-season tropical activity more common in the western Atlantic, the first key is that warmer than average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in these areas have a statistically significant relationship with an active October. This year, the western Caribbean is warmer than average by a few degrees, though not as warm as 2020, while the Gulf has been churned up by Ida and friends and SSTs are around normal there.

The second important consideration lies in the Pacific Ocean. NOAA has placed the Equatorial Pacific on a “La Niña Watch,” meaning that milder than normal SSTs west of South America are likely to continue cooling, and an official La Niña event should return in the next month or two.

La Niña is a particular concern in October, as it promotes a reduction of vertical wind shear over the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. As these are the favored breeding grounds for late-season tropical storms, a La Niña often acts to delay the end the hurricane season.

Last year’s moderate La Niña was an extreme example of this: 2020’s head-spinning five major hurricanes after October 1 smashed the previous record of two, and Hurricane Zeta became the latest-ever U.S. major hurricane landfall on October 28. This year, the developing La Niña is expected to be weaker than it was in October 2020, though still supportive of a busy late season.

A recent paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society investigating the extraordinary hurricane activity of October and November 2020 (I’ll pause for you to retrieve your copy of BAMS from the coffee table or bathroom) found that even a simple model accounting for only western Atlantic SSTs and El Niño/La Niña conditions could skillfully predict late-season tropical activity.

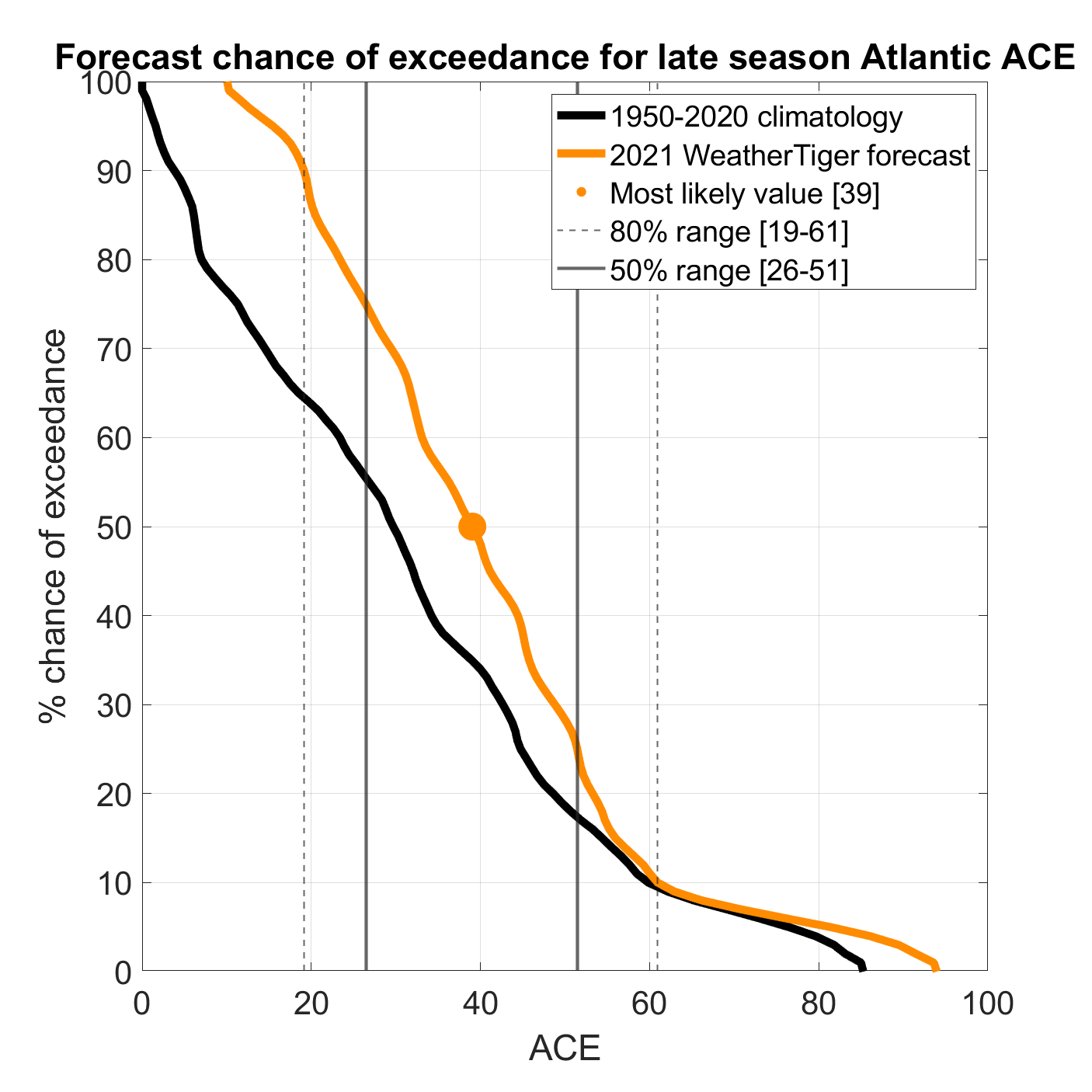

WeatherTiger’s seasonal forecast model is a little more complicated than that, but confirms the active signal suggested by this study. Using July and August oceanic and atmospheric inputs, our algorithm suggests a most likely outcome of total storm energy after September 25th of around 30% greater than the average year over 1950-2020. While this is above normal, the same model last year predicted double the typical amount of late season activity, so a “low-calorie 2020” solution tracks with observed Atlantic SST and Pacific La Niña trends.

These predictive analytics suggest a solid chance of a hurricane strike somewhere in Florida before the end of the season. Since 1851, there have been 40 Florida hurricane landfalls after October 1st, including 15 major hurricanes. Given WeatherTiger’s models suggests a risk profile around one-third greater than a normal late season, we estimate that Florida has roughly 1-in-3 odds of a hurricane landfall and 1-in-8 chances of a major hurricane landfall after October 1.

In summary, the current tropical reprieve may last for another couple of weeks, as relatively unfavorable upper-level winds work their way across the Atlantic in late September. Winds aloft are favored to tip back into a more supportive regime for storm formation in the Caribbean and western Atlantic early in October, at which point steering currents may periodically open the door for anything that could develop, as hinted in our August outlook.

Remember that seasonal forecasting is interpreting shadows on the cave wall, and all possibilities, good and bad, remain possible. There’s nothing to do at this point other than stay prepared and accept the difficult truth that we may be done with hurricane season, but hurricane season is not necessarily done with us. As much as we’d like to will this exhausting season away, hurricane history and a developing La Niña indicate that through at least late October, we need to keep watching the skies.