Wayward Geese: WeatherTiger's Weekly Column for June 24th

A flock of tropical waves is off-course for late June. Meaning?

Welcome to WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch! On Thursday afternoons through October, we’ll be releasing a long-form column digging deeper on current conditions, or some other aspect of tropical meteorology, forecasting, or history if the Atlantic is quiet. Paid subscribers will receive these columns and be able to comment and ask questions, as well as get all of our daily forecast briefings, in-depth forecasts and video discussions during Florida hurricane threats, live landfall coverage, and expanded seasonal outlooks. Free subscribers subscribers will also receive this weekly forecast column and selected storm coverage. Sign up below to get WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch newsletters all season long.

The summer solstice is a time of subtle change in the natural world. Daylight hours peak, then decline by a few seconds each day. Florida’s majestic ground holes refill with water. Awkward teenage and young adult geese learn the ancient secrets of blocking sidewalks from their elders. Sunrise, sunset, swiftly fly the years, if not the geese.

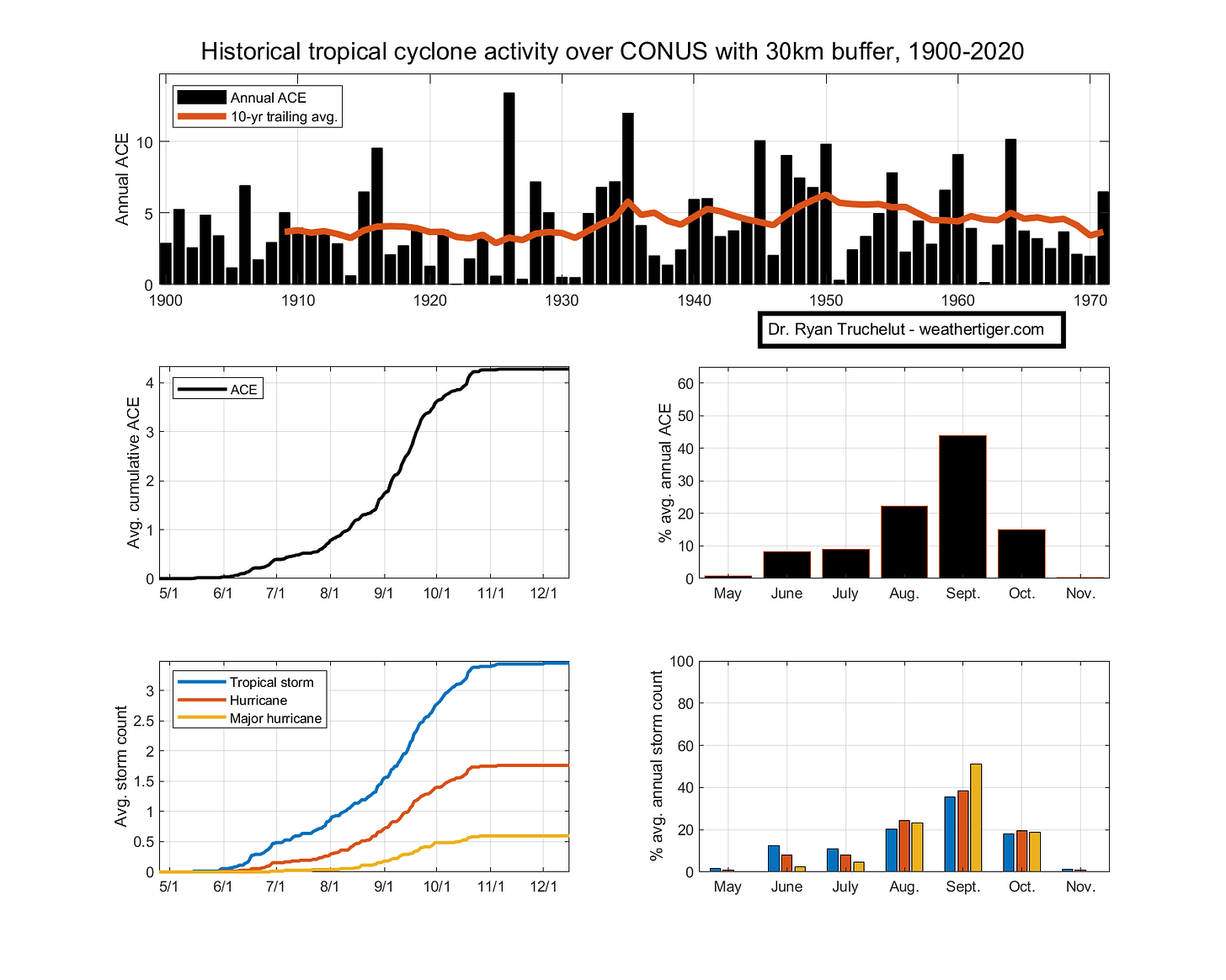

In the Tropics, late June marks a pivot point as well, with the expected daily rate of U.S. tropical cyclone landfalls dropping from around 2 per 100 years on June 20th to more like 1 per 100 years by the end of the first week of July. Claudette timed that mid-June peak in U.S. tropical storm landfall frequency precisely last week, though it stretched the definition of landfall by initially attaining tropical storm status over Louisiana due to friction with land tightening up its loose circulation.

The primary impact of Claudette, heavy rainfall, was not sensitive to this taxonomical peculiarity, and general accumulations of 4 to 8” were observed from eastern Louisiana to the western Florida Panhandle, causing localized flash flooding. Several destructive tornadoes also occurred in association with Claudette’s outer bands, as is typical for the right flank of a landfalling tropical storm or hurricane.

There are no immediate threats on the heels of Claudette. The decline in historical landfall frequency into July is caused by the supply of stalled fronts and Central American gyres that trigger development close to the continental U.S. in June dwindling, while conditions usually remain unfavorable for hurricane activity in the eastern Atlantic.

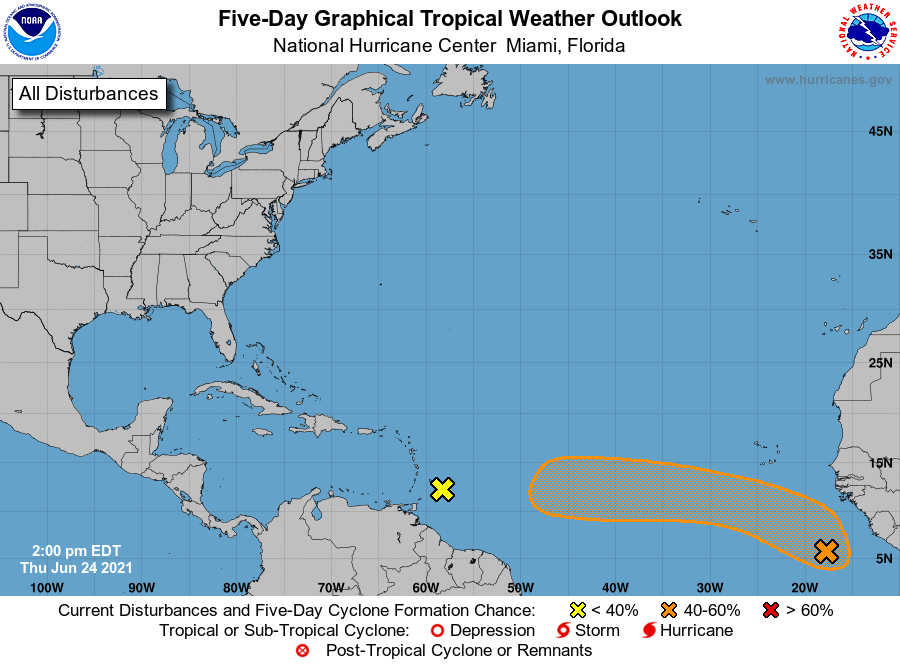

The key word there is usually, because the regions to watch in the Atlantic are located well east of the typical regions for potential storm development in late June: two tropical waves traversing the Main Development Region between the Lesser Antilles and west Africa. The first of these, a wave moving through the Windward Islands, made a brief run at spinning up a few days ago, but is now embedded in a region of strong wind shear over the eastern Caribbean. This shear will make tropical development of this wave impossible in the week ahead.

The second wave is in an even stranger location for early season formation, barely north of the Equator and just west of the African coast. Only three unnamed tropical depressions have formed east of 45°W in June, so if a tropical storm were to develop from this it would be something that has never happened before in history, like adequate parking at Trader Joe’s or a goose voluntarily de-escalating a conflict.

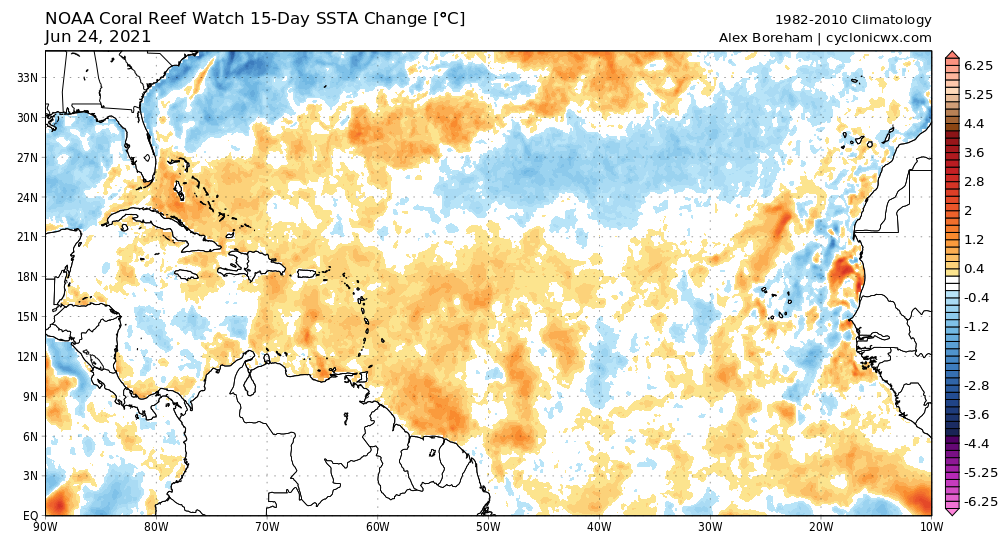

Despite these climatological headwinds, this wave has a puncher’s chance of further organization. Convection is extensive near an area of low-level rotation, with rising motion driven by oddly favorable upper-level outflow. Tepid ocean temperatures usually inhibit development in the eastern Atlantic prior to late July, but in this case the disturbance is far enough south that the waters are warm enough to support slow organization.

No development is still the most likely outcome from this wave. Rare events are rare for a reason, yet there is a plausible tightrope to some development that this disturbance could navigate over the next five to seven days as it continues west. The wave is literally a third of the world away from the U.S. at this point, so the odds of any eventual impacts are vanishingly small. Still, it’s worth watching the progress of both disturbances over the next two weeks, particularly as the development of such waves once they reach the western Caribbean is far less unusual for early July.

Overall, the most alarming aspect of these waves is that needing to watch the eastern Atlantic in summer is an ill portent. Years with early Main Development Region storms, like 1933, 1979, 1996, 2005, or 2017, tend to continue active through the peak season. This year also is poised to follow the tendency of the past five in notably warming the eastern Atlantic relative to normal in summer (above). If those trends continue for the season’s climatological peak in August and September, much like a goose blocking the sidewalk, it’s not clear how we get around it without feathers flying. Keep watching the skies.