Under the Dome: WeatherTiger's Weekly Column for July 29th

Heat domes are the meteorological buzzword of summer. Does the Tropical Atlantic have any viral content to contribute in the near future?

WeatherTiger’s weekly Thursday column is provided free to all subscribers. To get our complete storm coverage, upgrade to premium for as little as $8 to get daily forecast briefings, in-depth forecasts and videos during Florida hurricane threats, live landfall coverage, expanded seasonal outlooks, and the ability to comment and ask questions. Click below to sign up below now, or to share the Hurricane Watch with your friends and family.

Belying the stereotype of meteorologists as well-rounded individuals who don’t just sit around talking about the weather all the time, some meteorologist friends and I were discussing last month what the next piece of weather nomenclature to explode into the public consciousness might be.

As it turns out, we only needed to wait a few days for the answer: heat dome. The like polar vortex in winter 2014 or derecho last year, 2021 is the summer of the dome—and these weather features are also tied to the recent feast or famine in Atlantic hurricane activity.

You may be more familiar with “heat domes” by their actual name, ridges of high pressure. High pressure is marked by sinking air aloft, which warms as it compresses. This is called adiabatic warming. Contrary to The Day After Tomorrow, you cannot repeal the ideal gas law and freeze the Empire State Building by bringing cold air from the upper atmosphere down to the ground—if compressed to surface pressure, air from the cruising altitude of jets would actually be extremely hot. Remarkably, ignoring adiabatic warming was only the second worst mistake in The Day After Tomorrow, after casting Dennis Quaid rather than the indomitable Nic Cage as plucky climatologist Jack Hall.

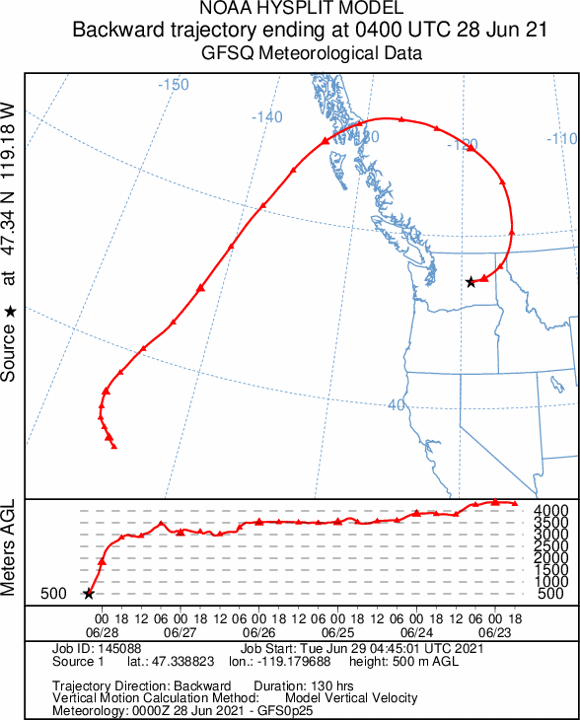

Along those lines, the historic June heatwave that was an extinction level event for the Pacific Northwest’s native Sasquatches was driven not by desert air advecting in from the south, but rather a stagnant airmass that slowly looped down to ground level from above. Since then, an unusually amplified jet stream over North America has led to persistent high pressure and heat for the central and western U.S., and a relatively mild summer for the south and east.

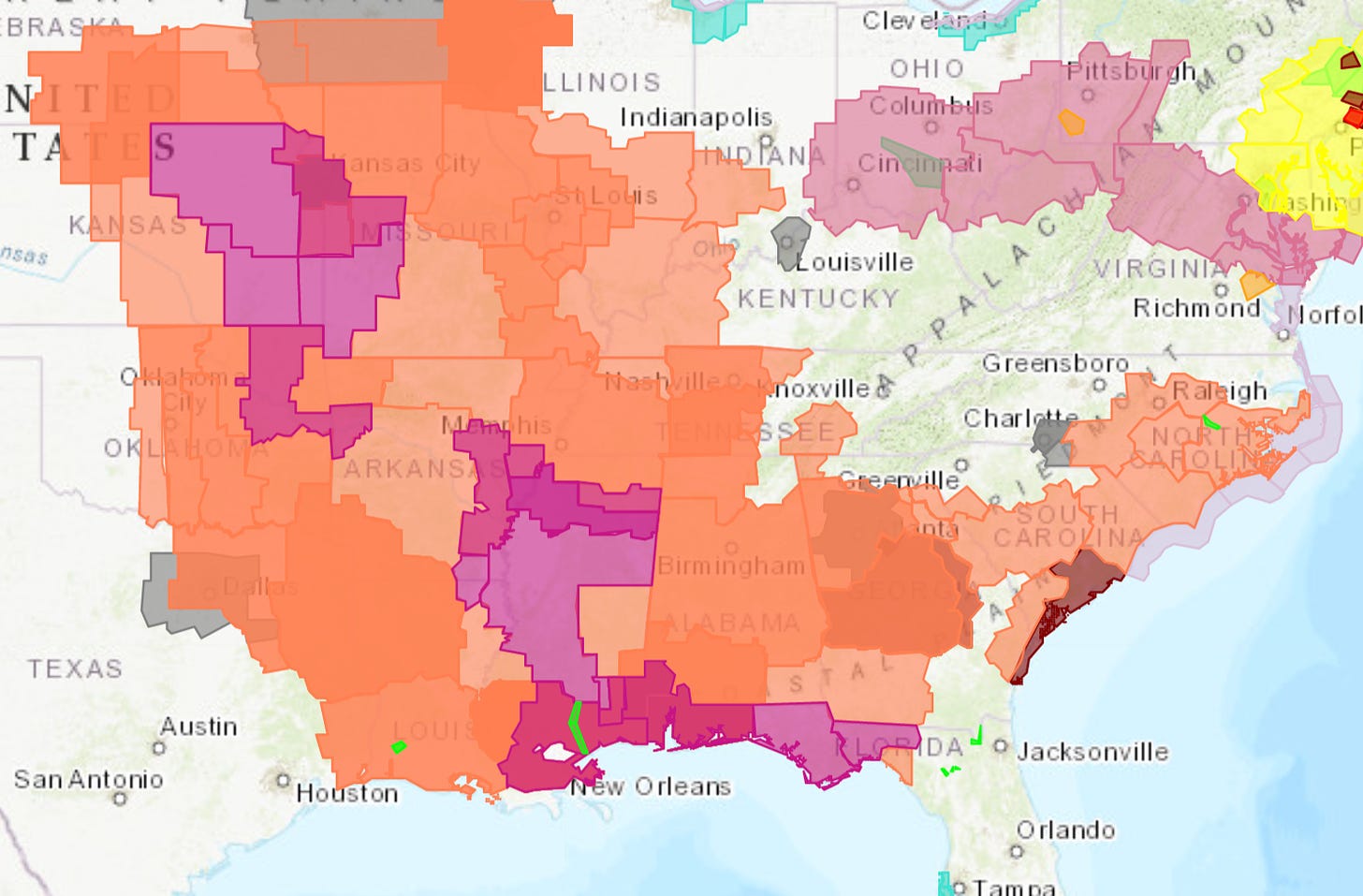

Until now. With apologies to Stephen King and Spider-Pig, it is the Southeast’s turn to be under the dome for a few days. Heat Advisories are in effect for much of the Deep South through the weekend, though above normal rainfall coverage is expected to return to Florida next week.

A fringe benefit of the dominant pattern this July is that it has been unfavorable for tropical development in the Atlantic. In fact, since Elsa dissipated over three weeks ago, only two modest disturbances have merited mention in the National Hurricane Center’s Tropical Weather Outlooks.

Why so quiet following a busy June? The Atlantic hurricane season’s tendency to have intense two- to four-week bursts followed by extended lulls arises from the existence of global-scale atmospheric waves. Like waves on the ocean, these waves move in a somewhat predictable way once established. Identification of global-scale waves can highlight broad regions of enhanced tropical development or even landfall risks weeks ahead of time. However, specific storm tracks cannot be predicted, and these forecast methods don’t always work as the required patterns or waves are often weak or absent.

One such wave is the Madden-Julian Oscillation, or MJO. The MJO is a global pattern of winds aloft influencing the location and extent of tropical convection. At the simplest level, think about thunderstorms sending masses of moist, unstable air rising in one part of the Tropics. In this atmosphere we obey the laws of thermodynamics, so that rising motion must be compensated by sinking, stable air in another part of the Tropics. This symbiotic pattern of wetter and drier regions moves east as a unit, and typically completes a full circumnavigation of the Equator in 45 to 60 days.

When the MJO or similar phenomena promote upward motion over the Atlantic, hurricane development and rapid strengthening is much more common. According to research performed by Phil Klotzbach of Colorado State University, aggregate U.S. hurricane damage in the convectively active phases of the MJO since the early 1900s is nearly three times greater than during the suppressed Atlantic phases.

The Atlantic has been in an inactive phase of a moderate strength MJO for much of July, putting the kibosh on tropical disturbances and favoring central U.S. heat. However, more favorable conditions for Atlantic convection may resume in the second week of August. While I don’t expect an immediate return of threatening tropical activity, the return of a pattern yielding more areas of concern or possible development in mid-August is in good agreement with climatology.

Overall, I don’t look forward to the day that the MJO becomes a pop buzzword, because it probably means the Tropical Atlantic is in a state of MJO-driven hyperactivity. Fortunately, nothing like that is in our immediate future. Heat domes may be to 2021 what Danny Almonte and shark attacks were to summer 2001, but much like Kenny Rogers, I’d rather be roasting. Keep watching the skies.

Next update: Our regular daily briefing will resume tomorrow for paid subscribers.