Stump the Tiger, Double Majoring Edition: WeatherTiger Weekly Column for Oct. 25th

Your burning questions about Major Hurricanes Helene and Milton, answered, plus the deal with potential development in the Caribbean next week.

WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch is a reader-supported publication. Paid subscribers get Florida-focused daily tropical briefings, plus coverage of every U.S. hurricane threat, our exclusive real-time seasonal forecast model, and the ability to comment and ask questions.

In a nation so divided that two separate touring bands claim to be Sublime, one thing all can agree on is the desire for hurricane season to be over. As October days dwindle to a precious few and 97% of U.S. landfall activity now lies behind us, Floridians attempting to emerge from our physical bunkers and psychological hunkers regard the prospect for further tropical threats with contempt.

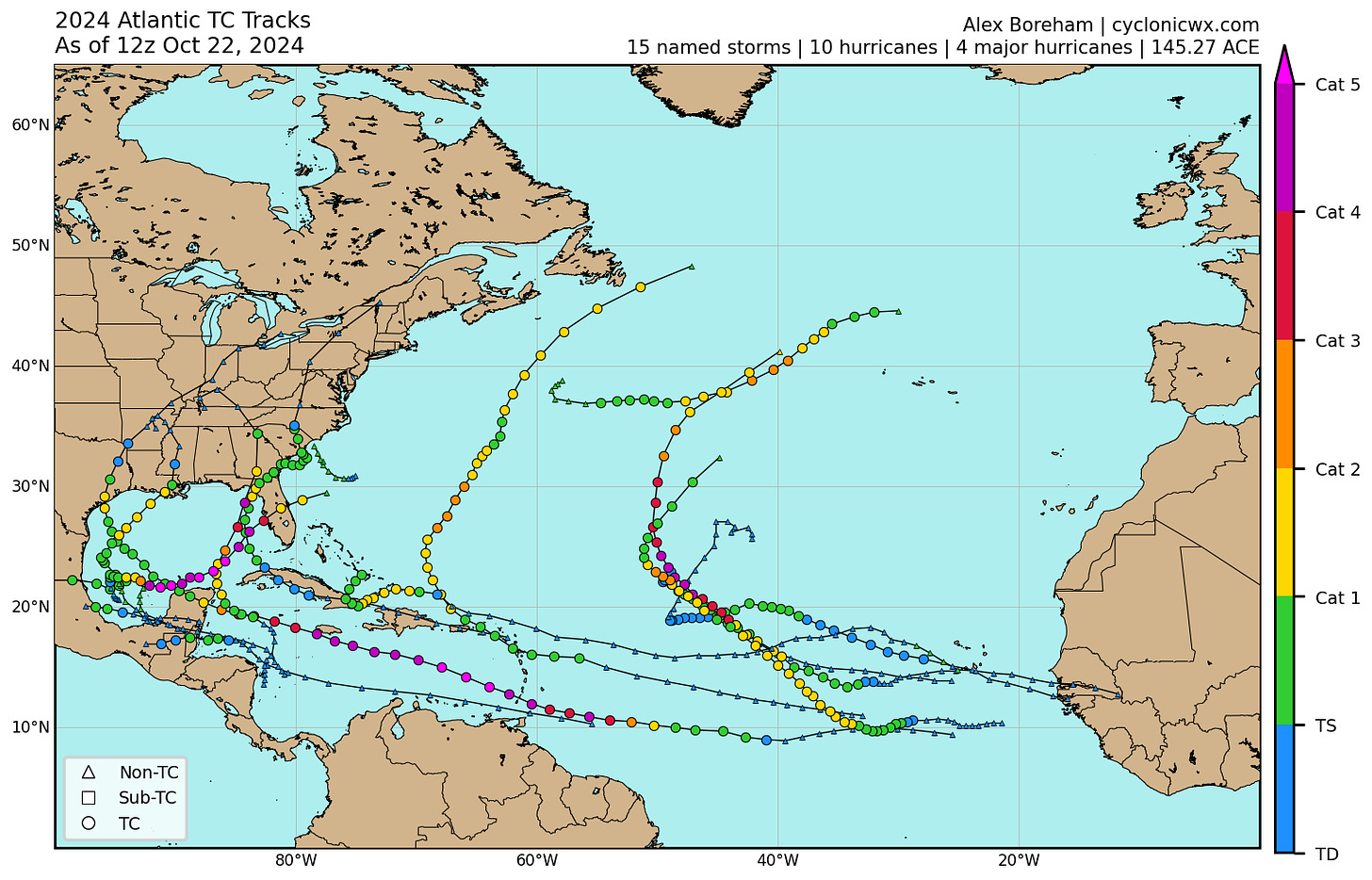

That is because, quite simply, we are tired. We are tired because the 2024 hurricane season punched us harder than any in a generation. This year was the first time since 2005 that Florida recorded three hurricane landfalls, two of which were Category 3 or above. Not only that, but Helene and Milton were both unusual storms with few historical precedents to anchor expectations.

Understandably, you have questions, and answering tough but fair questions is what my annual Stump the Tiger column is about. This year, your queries about Helene and Milton clustered around three themes: Helene’s winds over land, Milton’s tornadoes, and whether 2024 is just what life is like now.

Alicia A. and Ron C. are curious how Helene’s recorded wind gusts in Tallahassee and Perry were so low relative to the hurricane’s 140 mph official landfall intensity. Richard W. from Sarasota poses a similar question about Milton’s winds south of Tampa Bay.

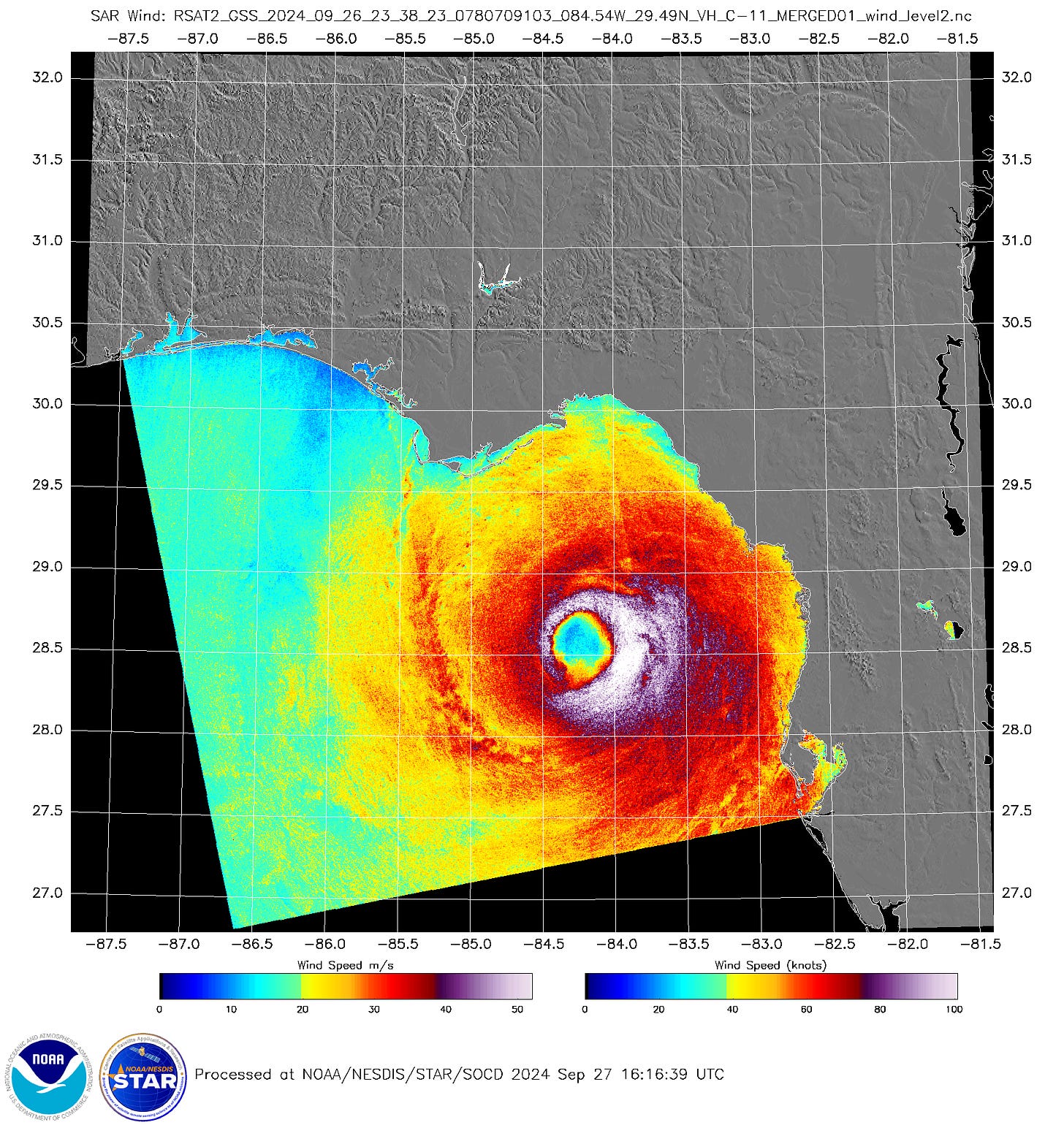

A common controversy in the wake of many U.S. hurricane landfalls is the disparity between NHC wind estimates and comparatively underwhelming land-based wind observations, with Helene a notable example. There’s a couple of general factors in play and two more specific to the Big Bend.

First, peak sustained winds in a hurricane always occur over open waters. Because Earth’s surface is not a smooth, frictionless sheet but rife with turbulence-inducing buildings and trees, sustained winds drop by at least 30% going from water to land, often more. Additionally, estimating maximum winds is an inexact science. Even reviewing Hurricane Hunter, radar, and all other storm data in the off-season, the NHC’s final intensity estimates have an inherent uncertainty of plus or minus 10%. If we assume for argument that Helene’s maximum winds were 10% weaker than the operational 140 mph landfall intensity, then lop off another 35% for friction, the highest sustained winds over land are in the Category 1 range.

Of course, instruments actually have to record those winds. Weather observations are notably sparse in the rural section of Florida’s Big Bend where Helene struck, and there’s no stations in eastern Taylor County where satellite estimates suggest the highest gusts over land occurred. With Helene racing north-northeast at 30 mph at landfall, those estimates also showed by far the strongest winds to be in the eastern quarter of the storm. Areas where winds were out of the south, to the southeast of Perry, were likely where sustained winds may have been around 90 mph, with gusts to 115 mph or more. Compare that to observed sustained winds of around 60 mph and gusts to 100 mph in Perry, where the strongest winds were from the east, and sustained winds from the north and northeast of 40 to 45 mph with gusts to around 65 mph in Tallahassee.

I’m not complaining that Tallahassee’s annual tradition of peering into the cyclonic abyss ended with modest damage, but that luck is likely a function of Helene’s fast motion and possible inefficiency in bringing the stronger winds aloft down to the surface at the time of landfall, plus the usual friction effects.

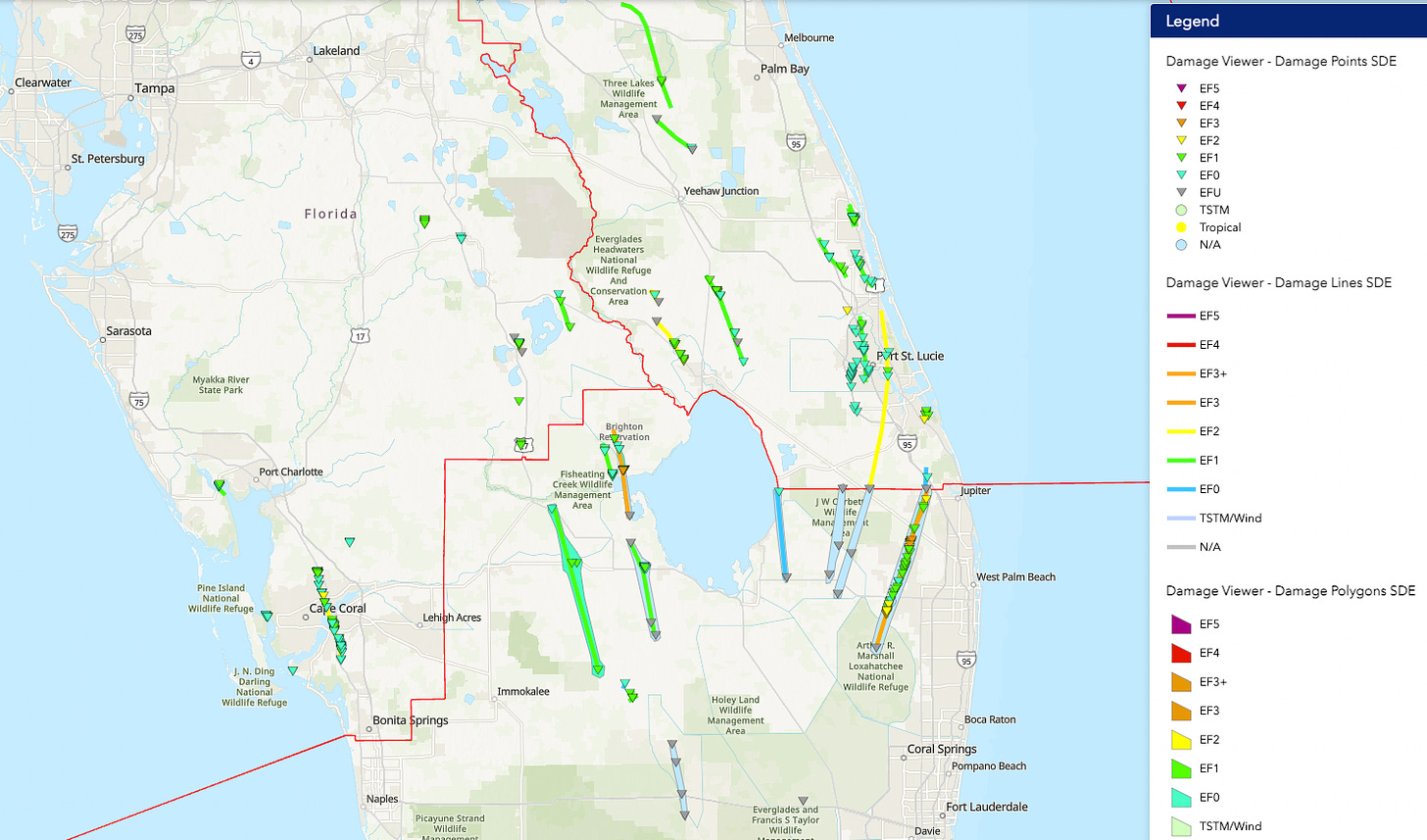

Jeannette B. from Martin County, Irwin F., and Michael D., among others, want to know more about how Hurricane Milton caused such a widespread outbreak of severe tornadoes in South Florida.

Tornado outbreaks are common in landfalling hurricanes as land friction slows down a hurricane’s winds close to the surface more than winds higher off the ground. That creates wind shear that can set individual storm cells in outer bands spinning like a top, especially on the right side of a hurricane relative to its forward motion. Typically, these tornadoes are sheathed in heavy rainfall and short-lived, often with brief lead times for warnings.

What is not common in landfalling hurricanes are the long-tracking, supercell wedge tornadoes that Milton produced, which looked like something Tragic Backstory Woman and Bro with a Heart of Gold would have chased in 2wisters. Milton touched off three EF-3 tornadoes, an impressive percentage of the 40 or so “intense” tornadoes Florida has recorded in the last 75 years, amongst 39 Milton-spawned tornadoes confirmed by storm surveys to date. These were heralded by 126 Tornado Warnings from the National Weather Service, the most of any day in Florida weather history.

There are two reasons why Milton’s tornadic impacts were uniquely violent. First, by making its bizarre approach from the west, Milton was able to cleanly transport a hot and humid airmass from south to north into Florida straight from the Deep Tropics. This increased the instability of the atmosphere, or how quickly air rises from the ground to form thunderstorms. Second, as Milton was still a Category 5 while starting to interact with the jet stream, the wind shear over those thunderstorms was much more than in a weaker hurricane. Unfortunately, combining tropical instability and Midwest-style shear brings Midwest-style tornadoes.

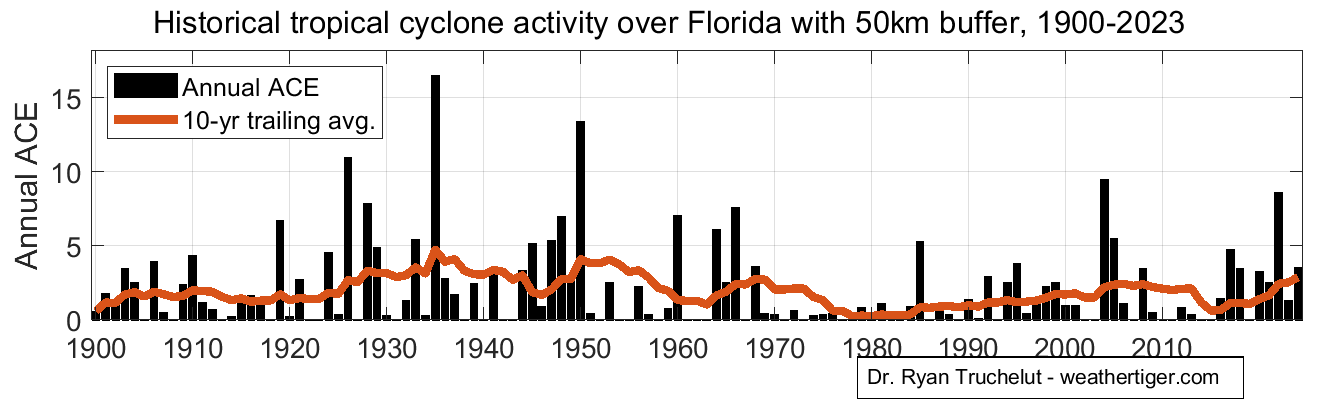

Ken and Sue H. from Winter Haven and Jim C. in the Panhandle would like to know if Helene and Milton represent a long-term trend in the frequency and severity of Florida hurricane landfalls.

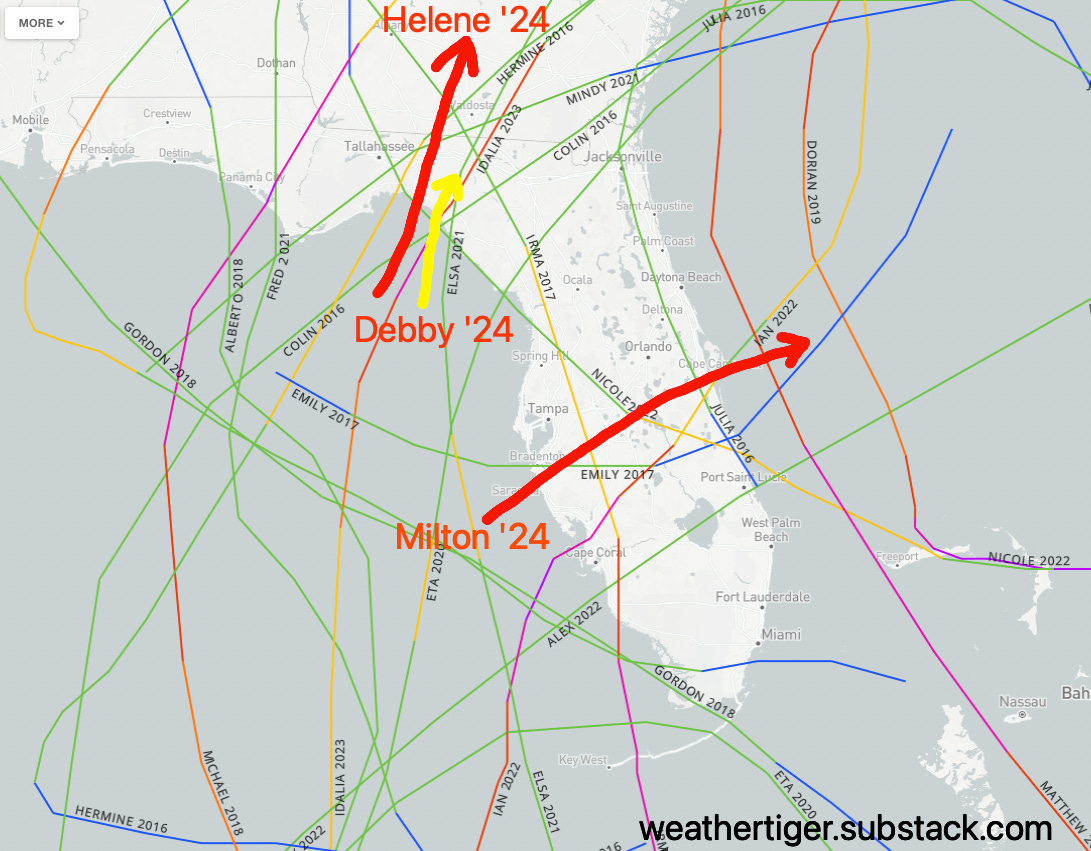

You’re probably aware that since 2016, Florida has notched 10 hurricanes, including six Category 3+ landfalls, plus another ten tropical storm strikes and two more high-impact major hurricanes passing offshore. That’s about three to four times the long-term norm, at a cost of around a quarter-trillion dollars. What you might not remember is that on the heels of the seven Florida hurricane strikes in 2004 and 2005, exactly zero hurricanes made landfall in Florida between 2006 and 2015.

Landfall climatology is chunky and known to make fools of those who make confident declarations about long-term changes in hurricane risk. Since 1900, there is no significant trend in how frequent or how severe hurricane landfalls have been in Florida, smoothing out quieter periods in the early and late 20th Century and more active periods in the mid-20th and early 21st Century. It wouldn’t shock me if a real trend towards more Gulf Coast landfalls is underway, but we don’t know yet if it is.

However, there is observational evidence and a strong theoretical argument for extremely rapid intensification becoming more common as oceanic heat content rises. Some historical Category 1 or 2 hurricanes have tracked like Michael, Idalia, Helene, and Milton, but there are not really any Category 4 or 5 storms like them on record prior to Gulf sea surface temperatures peaking in the upper 80s rather than the lower-to-mid 80s. Warm waters can’t create a hurricane from nothing without compliant atmospheric conditions, but it’s a decent bet that a category or two worth of intensity for Helene or Milton can be attributed to unnatural warming of the Gulf.

And finally, many are talking about rumors of another Florida hurricane landfall in November.

I’m texting a blanket STOP to quit to the sources of these rumors, and you should too. While there is a good chance of a tropical storm or hurricane developing in the western Caribbean through the first several days of November, most late-season tropical activity in that area eventually moves west into Central America, or northeast across Cuba, Jamaica, and Hispaniola. It’s not impossible that Florida might eventually be threatened in a week or more, but that’s beyond the range that models make skillful specific predictions. With only four November U.S. hurricane landfalls on record since 1851, the baseline risk of another significant impact this year is low.

To sort-of answer a bonus reader question, you also don’t need to worry because if a Florida threat develops, I will steal a B-52 Stratofortress and nuke it like Slim Pickens. I’m a scientist, and rationally I know that doing so would only create a radioactive hurricane. This one is more of an emotional truth, the only remaining kind.

With that, I’m going to attempt to log off from weekly columns for the 2024 hurricane season. Free subscribers, if you don’t hear from me until WeatherTiger’s annual season-in-review at the end of November, presume there is no continental U.S. threat, though I’ll be back earlier if necessary. Paid subscribers, your daily bulletins will continue until the season is done, particularly while storms or rumors of storms continue. Thanks again for the questions, and as always, I appreciate your trust and readership over this challenging year. Until next time, keep watching the skies.

Ryan, thank you as always for the analysis and humor. It’s been a rocky season in SWFL and only made better by your commentary. Funny, I can see Slim Pickens in my mind’s eye riding that nuclear bomb out of the B-52 in “Dr. Strangelove.” What a classic! Hope we don’t need you to do that in November. Keep up the great work, pal.

This was a particularly great column, thanks again!