June, Too Soon: WeatherTiger's Weekly Column for June 10th

In which we give thanks that June 2021 is not June 1886, for a variety of reasons.

Welcome to WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch! On Thursday afternoons through October, we’ll be releasing a long-form column digging deeper on current conditions, or some other aspect of tropical meteorology, forecasting, or history if the Atlantic is quiet. Paid subscribers will receive these columns and be able to comment and ask questions, as well as get all of our daily forecast briefings, in-depth forecasts and video discussions during Florida hurricane threats, live landfall coverage, and expanded seasonal outlooks. Free subscribers subscribers will also receive this weekly forecast column. Sign up below to get WeatherTiger’s Hurricane Watch newsletters all season long.

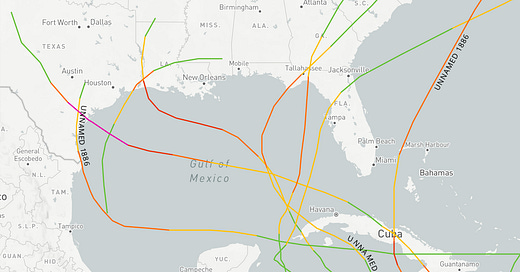

The potential for tropical development in the southern Gulf of Mexico heading into mid-June has been the proverbial pain in the liver just short of jaundice for the last week—an area of turning near Central America has neither become a more organized system, nor disappeared entirely. All indications are that this tropical limbo is likely to continue for the near future, with a slight possibility of a storm meandering towards the Gulf Coast around the end of next week.

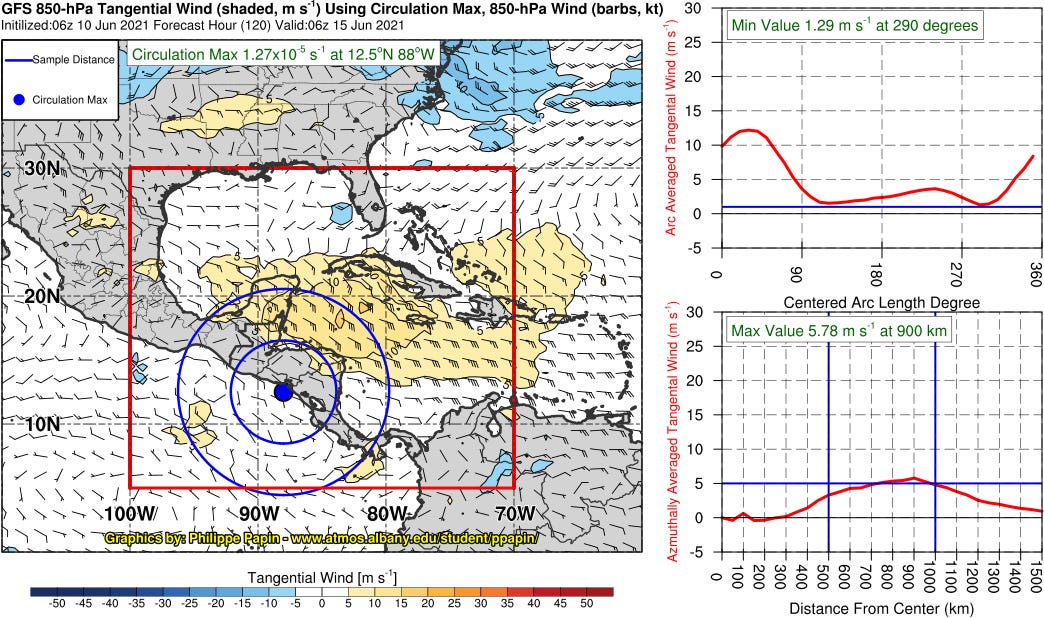

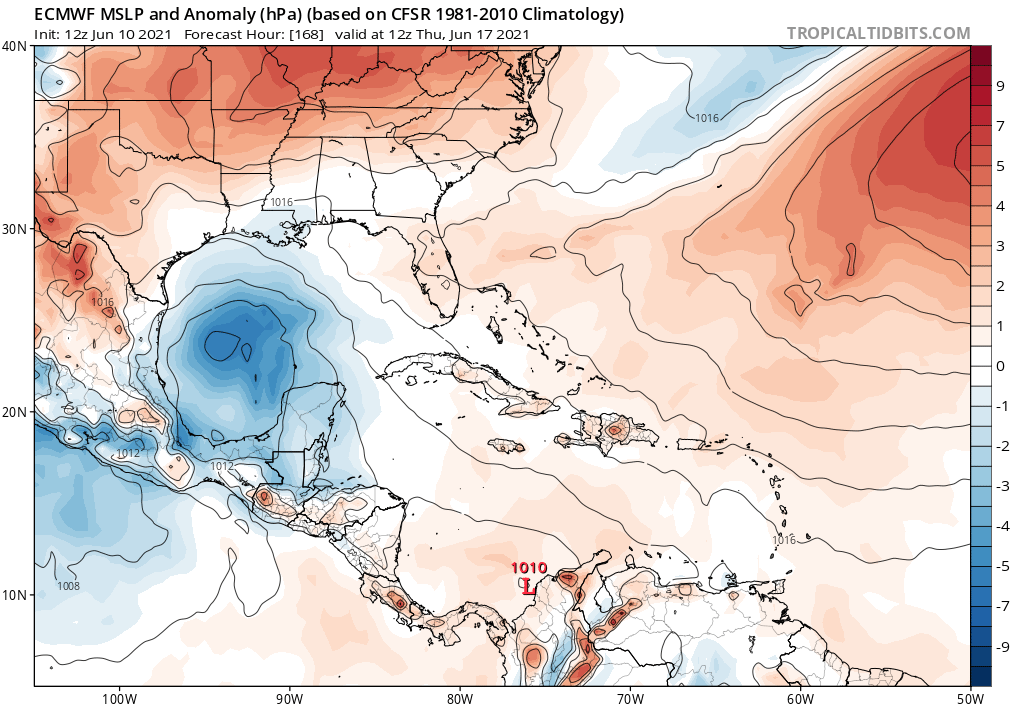

The reason is an expanse of cyclonic circulation in the low-level trade winds called a Central American Gyre, which currently spans much of the southern Gulf, western Caribbean, and eastern Pacific. Central American Gyres often develop in June or October, and are one of the most common predecessors to early- and late-season tropical storms.

Unfortunately, precise forecasts of when and where tropical development may occur within these gyres are difficult. Gyres usually have favorable conditions for convective complexes to develop, but the locations of the storm clusters within the broad circulation are driven by daytime heating, sea breeze interaction, and trade wind convergence patterns. While tropical storms sometimes develop from these clusters, these factors are not things computer models handle well.

That leaves us to simply acknowledge the climatological potential of the gyre pattern and wait. For the past week, models have intermittently been suggesting that a tropical storm could develop in the southern Gulf in 7 to 10 days, but the purported threat has not gotten any closer to the present. Upper-level winds may become a little more favorable for development by the middle of next week; should tropical storm development occur, climatology suggests that the Mexican Gulf Coast or the western half of the U.S. Gulf Coast are the most likely regions to be threatened.

None of this is unusual for the initial month of hurricane season. A June tropical storm develops in about two-thirds of years, usually in the Gulf of Mexico or Caribbean. June tropical activity tends to be weaker, particularly in the first half of the month: only one U.S. hurricane landfall (Alma in 1966) has occurred on or before June 15 since 1900. Because development usually occurs close to the coast, almost 50% of June tropical storms eventually make a U.S. landfall, compared to about 25% for the rest of the season.

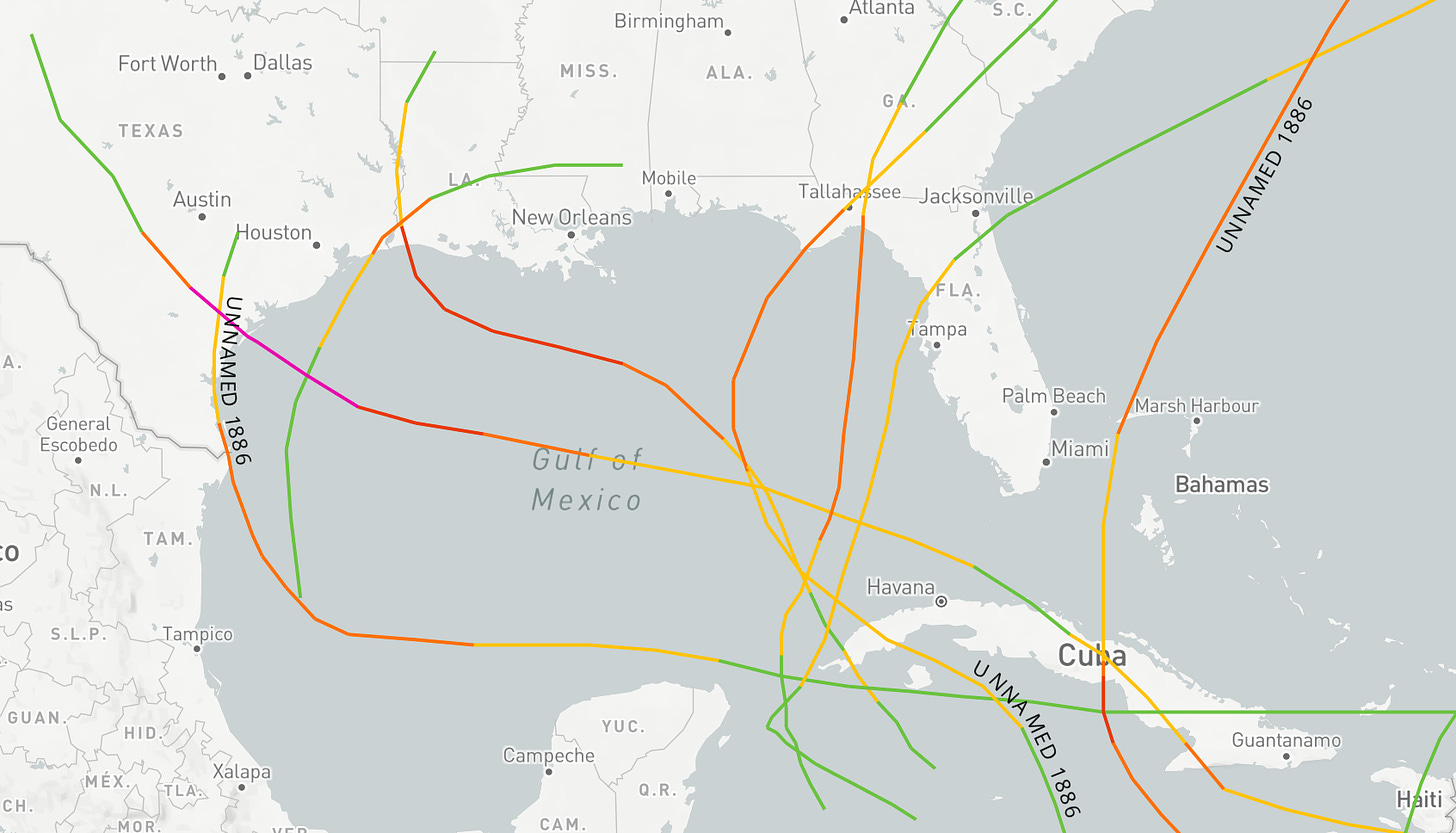

There are a few historical exceptions to this rule in the hurricane history of the late 1800s, particularly the wild hurricane season of 1886. Despite weather observation networks paling in comparison to the modern day, seven separate hurricane landfalls were noted on the U.S. Gulf Coast that year. This remains the single-season record, exceeding the paltry six U.S. hurricane landfalls in 1985, 2004, 2005, and 2020.

The torrid pace of landfalls of June 1886 is unequaled in Atlantic climatology, with three Category 2 hurricane hits occurring on three consecutive weeks. The first of these made landfall in eastern Texas on June 14. The following pair managed an even more impressively hostile feat, striking nearly the same location on the Florida Panhandle coast in quick succession. The first, on June 21, a was a so-called “Great Hurricane” with 100 mph sustained winds that made landfall near Apalachicola, bringing widespread coastal flooding to Apalachee Bay and the Big Bend.

Remarkably, a second Category 2 made landfall near St. Marks on June 30. Sustained winds of 80 mph were measured in Tallahassee with this one, and newspapers reported extensive crop damage and gusts strong enough to push railroad cars down the tracks. To make matters worse, a third hurricane, likely of Category 1 intensity, struck between Tampa and Cedar Key in mid-July. The strongest landfall of the 1886 season was the Category 4 Indianola (Texas) hurricane on August 20, which is still the seventh-lowest pressure on record for U.S. landfalls.

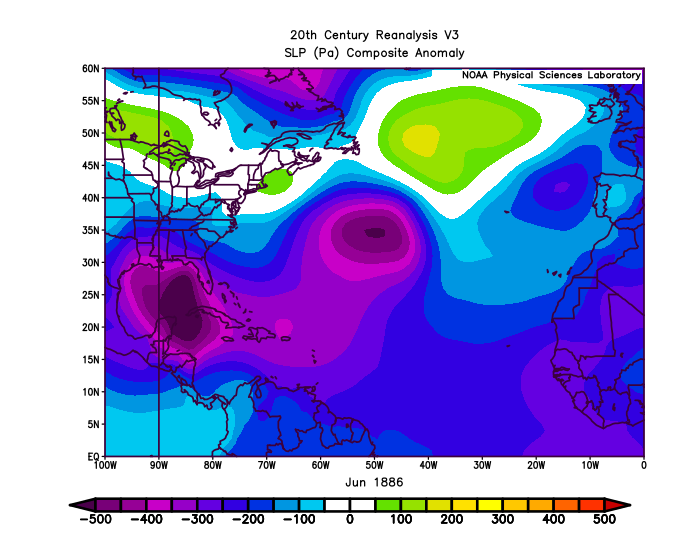

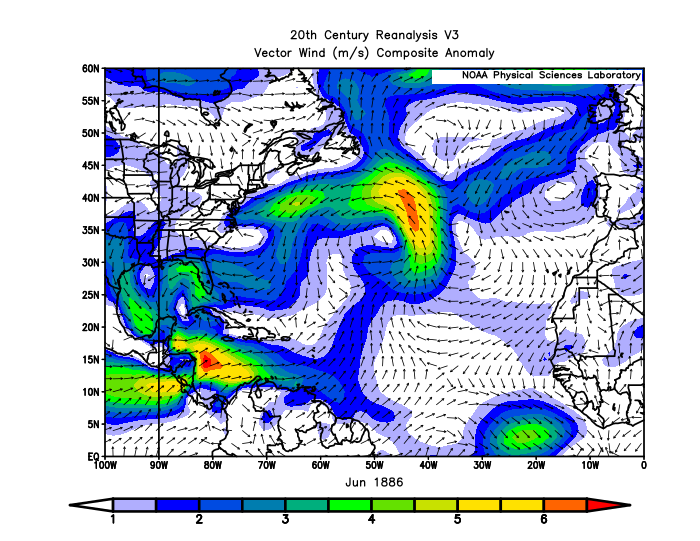

Why was summer 1886 so absurdly hyperactive? While some say the answer is the red-hot debate between Mugwumps, Stalwarts, and Half-Breeds on proposed federal civil service reforms, an extremely strong Central American Gyre is a more likely culprit. All three June hurricanes emerged from the southern Gulf or western Caribbean, where surface pressures were well below normal throughout the month. Unusually weak trade winds in the eastern Pacific also added atypically moist inflow to the gyre convection. That plus a heaping dollop of bad luck led to a bizarre triple-double of June category 2 hurricane strikes.

There is no indication of anything like that kind of hyperactivity coming from the Central American Gyre in the weeks ahead, which would certainly cause infinity percent more power outages in Florida in 2021 than 1886. Nevertheless, hurricane history says to keep an eye to the south in June. Keep watching the skies.

Next update: A daily briefing will be issued tomorrow by 3 p.m.